The Project Gutenberg EBook of Boy Woodburn, by Alfred Ollivant

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Boy Woodburn

A Story of the Sussex Downs

Author: Alfred Ollivant

Release Date: March 11, 2006 [EBook #17965]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BOY WOODBURN ***

Produced by David Garcia, Graeme Mackreth and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By the same Author:

BOB, SON OF BATTLE

THE GENTLEMAN

REDCOAT CAPTAIN

THE ROYAL ROAD

THE BROWN MARE

FOUR-POUND-THE-SECOND

"Look at that head-piece. He's all the while a-thinkin', that hoss is.

That's the way he's bred."

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1918

Copyright, 1918, by

Doubleday, Page & Company

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign

languages including the Scandinavian

TO

THE MOTHER

OF

LAUGHTER

CHAPTER

The Spring Meeting at Polefax was always Old Mat's day out. And it was part of the accepted order of things that he should come to the Meeting driving in his American buggy behind the horse with which later in the day he meant to win the Hunters' Steeplechase.

There were very few sporting men who remembered the day when Mat had not been a leading figure in the racing world. For sixty years he had been training jumpers, and he looked as if he would continue to train them till the end of time. Once it may be supposed he had been Young Mat, but he had been Old Mat now as long as most could recall. In all these years, indeed, he had changed very little. He trained his horses to-day at Putnam's, the farm in the village of Cuckmere, over the green billow of the Downs, just as he had done in the beginning; and he trained the same kind of horses in the same kind of way, which was entirely different from that of other trainers.

Mat rarely had a good horse in his stable, and never a bad one. He kept his horses in old barns and farm-stables, turning them out on to the chalk Downs in all seasons of the year with little shelter but the lee of a haystack or an occasional shed.

"I don't keep my hosses in no 'ot-house," he would say. "A hoss wants a heart, not a hot-water bottle. He'll get it on the chalk, let him be."

But if his horses were rough, they stood up and they stayed.

And that was all he wanted: for Mat never trained anything but jumpers.

"Flat racin' for flats," was a favourite saying of his. "'Chasin' for class."

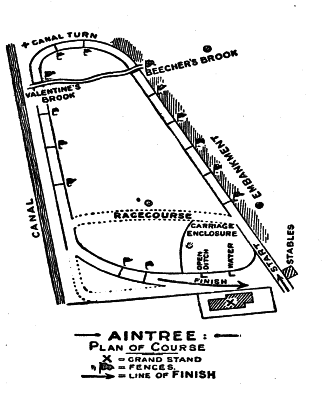

And many of his wins have become historic; notably the Grand National in the year of Sedan—when Merry Andrew, who had three legs and one lung, so the story went, won for him by two lengths; and thirty years later Cannibal's still more astounding victory in the same race, when Monkey Brand out-jockeyed Chukkers Childers, the American crack, in one of the most desperate set-to's in the annals of Aintree.

There is a famous caricature of Mat leading in the winner on the first of these occasions. He looked then much as he does to-day—like Humpty-Dumpty of the nursery ballad; but he grew always more Humpty-Dumptyish with the years. His round red head, bald and shining, sat like a poached egg between the enormous spread of his shoulders. His neck, always short, grew shorter and finally disappeared; and his crisp, pink face had the air of one who finds breathing a perpetually increasing difficulty.

In build Mat was very short, and very broad; and his legs were so thin that it was no wonder they were somewhat bowed beneath their load. Far back in the Dark Ages, when his body was more on a par with his legs, it was rumoured that Mat had himself won hunt-races.

"Then my body went on, or rayther spread out," he would tell his intimates, "while me legs stayed where they was. So Mat become a trainer 'stead of a jockey."

And Mat's legs were not the only part of him that had stayed as they were in those remote days. He wore the same clothes now as then; or if not the identical clothes, as many averred, clothes of the identical cut. Younger trainers, who were fond of having their joke with the old man, would often inquire of him,

"Who's your tailor, Mat?"

To which the invariable answer in the familiar wheeze was,

"He died reign o' William the Fo'th, my son. Don't you wish he'd lived to show your Snips how to cut a coat?"

Mat indeed was distinctly early Victorian in his dress. He always wore a stock instead of a tie, and the felt hat with a flat top and broad-curled brim, which a rising young Radical statesman, for whom Mat had once trained, had imitated. He walked with a curious and characteristic lilt, as of a boy, rising on his toes as though reaching after heaven. And his eye underlined, as it were, the mischievous gaiety of his walk. It was a baffling eye: bright, blue, merry as a robin's and very shrewd; "the eye of a cherubim," Mat once described it himself. When it turned on you, grave yet twinkling, you knew that it summed you up, saw through you, was aware of your wickedness, condoned it, pitied you, comforted you, and bade you rejoice in the world and its crooked ways. It was an innocent eye, a dewy eye, and yet a mighty knowing one. Whether the owner of the eye was a saint or a sinner you could not affirm. Therefore it bade you beware what you said, what you did, and not least, what you thought, while its mild yet radiant beams were turned upon you. One thing was quite certain: that blue eye had seen a great deal. More, it had enjoyed the seeing. And its owner had a way of wiping it as he ended some tale of rascality, successful or exposed, with his habitual cliché—"I wep a tear. I did reelly," which made you realize that the only tears it had in fact ever wept were in truth tears of suppressed laughter over the foolishness of mortals. It had never mourned over a lost sinner, though it had often winked over one. And it had profound and impenetrable reserves.

And the trainer's ups and downs in life, if all the stories were true, had been amazing. At one time it was said that he was worth a cool £100,000, and at another a minus quantity. But rich or poor, he never changed his life by an iota, jogging soberly along his appointed if somewhat tortuous way.

Old Mat was nothing if not a character. And if he was by no means more scrupulous than the rest of his profession, he had certain steadfast virtues not always to be found in his brethren of the Turf. He never drank, he never smoked, and, win or lose, he never swore. A great raconteur, his stories were most amusing and never obscene. And when late in life he married Patience Longstaffe, the daughter of the well-known preacher of God-First farm on the North of the Downs between Lewes and Cuckmere, nobody was much surprised. As Mr. Haggard, the Vicar of Cuckmere, said,

"Mat could always be expected to do the unexpected."

That Patience Longstaffe, the Puritan daughter of Preacher Joe, should marry the old trainer was a matter of amazement to all. But she did; and nobody had reason to think that she ever regretted it.

Patience Longstaffe became in time Ma Woodburn, though she remained Patience Longstaffe still.

Mat and his Ma had one daughter between them, known to all and sundry in the racing world as Boy Woodburn.

The Polefax Meeting was small and friendly; never taken very seriously by the fraternity, and left almost entirely to local talent. Old Mat described it always as reg'lar old-fashioned. The countryside made of it an annual holiday and flocked to the fields under Polefax Beacon to see the horses and to enjoy Old Mat, who was the accepted centre-piece.

The Grand Stand was formed of Sussex wains drawn up end to end; and the Paddock was just roped off.

Outside the ropes, at the foot of the huge green wave of the Downs, were the merry-go-rounds, the cocoanut-shies and wagons of the gypsies; while under a group of elms the carts and carriages of the local farmers and gentry were drawn up.

There, too, of course, was Mat's American buggy, a spidery concern, made to the old man's design, seated like a double dog-cart, and looking amongst the solid carts and carriages that flanked it like a ghost amongst mortals. It was the most observed vehicle of them all, partly because of its unusual make and shape, and partly because that was the famous shay in which year after year Mat drove over the Downs from Putnam's behind the horse with which he meant to win the Hunters' Steeplechase.

That race, always the last item on the programme, and the most looked-for, was about to begin.

The quality in the Paddock were climbing to their places in the wagons. The voices of the bookies were raised vociferously. The crowd jostled about them, eager to back Old Mat's old horse, Goosey Gander. They believed in the old man's luck, they believed in the old man's horse, they believed in the old man's jockey, Monkey Brand, almost as famous locally as his master.

A boy slipped into the Paddock and began to bet surreptitiously behind the dressing-tent.

He was fair, slight, and horsey. His stiff, tight choker, his horse-shoe pin, the cut of his breeches, his alert and wary air of a man of the world, all betrayed the racing-lad. From the corner of his mouth hung a cigarette waggishly a-rake; and his billycock had just the correct and knowing cock. He kept well under the lee of the tent; and if he was brazen, it was clear that he was sinning and fearful of discovery: for he had one eye always on the watch for the Avenging Angel who might swoop down on him at any moment.

"What price, Goosey Gander?" he asked in a voice harsh and cracking.

"Give you threes," replied the bookie.

"Do it in dollars," replied the boy, with the magnificent sang-froid of one who goes to ruin as a man of blood should go.

"And again?" asked the bookie.

The answer was never forth-coming; for the Avenging Angel, not unexpected, swept down upon the sinner with flaming sword.

She was in the shape of a girl about the lad's own age and size, fair as was he and slight, a flapper with a short thick straw-coloured plait. She came round the tent swift and terrible as a rapier, her steel-gray eyes flashing and fierce. Such determination on so young a face the bookie thought he had never seen. For a moment he expected to see her strike her victim. And the boy apparently expected the same, for he cowered back, putting up his hands as though to ward off a blow.

"Got you, sonny," said the bookie, and bolted with a half-hearted grin.

The girl never hesitated. She leapt upon her victim, keen and direct as a tigress.

"Give me that ticket!" she ordered in a deep bass voice whose earnestness was almost awful.

The boy had recovered from his first shock.

"It were only——"

"Give me that ticket!"

Reluctantly the lad obeyed.

"Spit out that cigarette!"

Again he obeyed. The girl put her broad flat heel on the chewed remnant and churned it into the mud.

"Any others?"

"No, Miss."

"You have!—I'll search you."

"Only a packet o' woodbines, Miss."

She pocketed them remorselessly.

"Leave the paddock!"

The boy went, slow and sullen. Then he became aware of people watching beyond the ropes and recovered himself with a jerk.

"Yes, Miss. Very good, Miss," he cried cheerfully, touched his hat, and began to run as on an errand.

It was a pretty piece of bluff. Boy Woodburn, in spite of her anger, marked it down to the credit side of the lad's account. When he was collared, Albert Edward kept his head. That would help him one day when he was caught in a squeeze in a big race and had to jockey to get through.

The roar from the crowd told her the race had started. She flashed back to the ropes, a slight figure, in simple blue serge, the radiant plait of her hair flapping as she ran.

Old Mat, standing a little behind the crowd at the ropes, had watched the scene.

"One o' my lads," he said in his mysterious wheeze to the big young man at his side. "'No smokin', swearin', or bettin' in my stable!'—that's Miss Boy's rule. Gets it from Mar." The girl passed them swiftly and the old man hid his betting-book behind him. "Well, Boy, sossed him?" he asked innocently.

"He's not the only one," retorted the girl.

"O, I'm not bettin', Boy," pleaded the old man in the whimsical whine which he adopted when addressing his daughter. "Don't go and tell your mother that now. It wouldn't be right. Reelly it wouldn't. I'm only makin' a note or two for Mr. Silver here."

The girl was lost in the crowd by the ropes.

"She'd ha' come and sossed me, too, only you was with me," wheezed the old man confidentially. "You stick close to me, there's a dear. You're like a putection to an old man. She won't do me no 'arm while you're by, de we."

The other smiled. He was an upstanding young man, with the shoulders and the bearing of a soldier; and there was something large and slow and elemental about him. He wore white riding-breeches and tan-coloured boots. The blood polo-pony under the elms, with the little group of coachmen and grooms gathered in an admiring circle round him, was his: and those who had seen Mat drive on to the course in the morning knew that the young man had ridden over the Downs from Putnam's with him.

Boy took her place at the ropes.

The young man found himself standing at her side. He did not watch the race. That keen young face at his side, so self-contained and strong, absorbed him.

Once the girl looked up swiftly, and he was aware of her gray eyes, that flashed in his and were instantly withdrawn, to follow the bob of the heads of the jockeys lifting over a fence on the far side of the course.

"Lul-like my glasses?" he asked, with a slight stutter.

"No," she said. "I can see."

Later she climbed on to the top of an upturned hamper. As the horses made the turn for home, he heard her draw her breath.

"Is he down?" he asked.

"No," she said. "He's got 'em beat."

"How do you know?"

"He's begun to ride," replied the girl briefly.

Old Mat was nibbling his pencil in the rear.

"How's it going, Boy?" he wheezed.

"All right," replied the girl. "He's through now."

The dirty green of the Woodburn colours topped the last fence; and Goosey Gander came lolloping down the straight, his jockey, head on shoulder, wary to the end, easing him home.

"That's a little bit o' better," said Old Mat comfortably, totting up his accounts.

"By Jove, he's a fine horseman!" cried the young man with boyish enthusiasm.

"Monkey Brand!" said the girl, without emotion. "One of the has-beens, I should say."

Boy Woodburn came leading the winner through the cheering crowd.

It was Old Mat's horse, Old Mat's race; and they had all got a bit on. They were pleased with themselves, pleased with the horse, pleased with the jockey, who, perched up aloft on the great sweating bay, his hands still mechanically at work, his little dark face shining, chaffed his chaffers in the voice of a Punchinello.

"Get off him, Monkey," called a joker; "get off quick afore he falls to pieces. Do!"

"Same as you do when I get talkin' to ye!" retorted the little jockey.

There was a roar of laughter at the expense of the joker, who turned suddenly nasty.

"Who said Chukkers?" he cried.

There was an instant of silence, and then some groans.

"Not me," replied the little jockey grimly.

A snigger rippled through the crowd.

"What you done with your old friend this time, Monkey?" somebody asked. "Laid him out again lately?"

"No such luck," the other answered. "He's beat it."

"Where is he then?"

The little jockey tossed his head backward.

"Gone back to God's Own Country to find his birf certificate. No flowers by request."

The reference was to the fact that Monkey's old-time enemy, the vanquished of Cannibal's National fifteen years before, Chukkers, the greatest of cross-country riders, was an American citizen of uncertain origin.

The thrust was received with a fresh outburst from the hilarious crowd. Monkey Brand's relations with his "old friend" were well known to all.

The little jockey prepared to dismount.

Amid a burst of jeers and cheers, he threw his leg over his horse's withers, slipped to the ground, stripped off the saddle, and limped off to the weighing machine.

Old Mat watched him go.

"On his hoss, on his day," he muttered confidentially to the young man, "Monkey Brand can show his heels to most of 'em yet."

"How old is he?" asked the other.

The old trainer frowned and shook his head mysteriously.

"You must never ask a jockey his age, no more than a woman," he said. "He come to me the year I was married, and that's twenty year since come Michaelmas. And when he come he looked much just the very same as he do now. Might ha' been any age atween ten and a hundred." He dropped his voice. "Only way he shows his years—he ain't so fond of fallin' as he was. And I don't blame him. Round about forty a man begins to get a bit brittle like."

He lilted off after his jockey.

Goosey Gander stood stripped of everything but his bridle, with dark flanks and lowered head reaching at his bit.

He was a typical Woodburn horse: a great upstanding bay, full of bone and quality. But he showed wear. A tube was in his throat, a leather-boot on each fore-leg, and he was bandaged to the hocks, both of which showed the serrated lines of the firing iron.

The girl in front of him pulled his sweating ears. Jim Silver watched with admiration not untinged with awe her stern young face. She was entirely unconscious of his gaze, and unaware of the people thronging her. Her whole spirit was concentrated on the dark and sweating head, trying to rub against her knees. The crowd pressed in upon her inconveniently.

"Give the lady a chance to breathe," cried the young man in his large and lazy voice.

The crowd withdrew a little.

"Say, Guv'nor!—do they call you Tinee?" called one.

"No; his name's Silver," said another. "They calls you Silver Mug, don't they, mister?"

"I believe so," replied the young man, unmoved.

He was fair game: for he was very big, clearly good-humoured, spick and span to a fault, and a member of another class.

They gathered with glee to the baiting.

"That ain't because of his name, stoopid. That's because he's got a silver linin' to his mug, ain't it, sir?"

"Silver!—gold, you mean. 'E breathes gold, that bloke do, and then it settles on the roof of his jaw. Say, Blokey, open your mug and let's 'ave a peep. I'll put a penny in."

A little red ball was run up an improvised pole. Old Mat was waving.

"All right," he called.

The girl led Goosey Gander out of the Paddock into the field at the back. Women in parti-coloured shawls selling oranges, labourers, riff-raff, and children were gathered about the merry-go-rounds and cocoanut-shies, listening apathetically to the hoarse exhortations of the owners to come and try their luck.

Silver followed the girl thoughtfully.

She led the winner past the side-shows toward the group of stately elms under which the carriages and carts were gathered.

The ejected stable-lad, Albert Edward, now in his shirt-sleeves, came toward her, carrying a bucket. The girl rinsed out the old horse's mouth. Then with swift, accustomed fingers she unlaced the leather-boots, and set to work to unwind a bandage.

Jim Silver watched her attentively and then began clumsily on the other bandage.

"No," she said. "Like so," and taking it from him unwound it in a trice.

The old horse shook himself.

"Go and fetch his rug from the buggy," ordered the girl, addressing Albert.

The lad went off.

The young man took off his long-waisted gray coat and flung it over the horse's loins, lining down.

Boy's gray eyes softened. Then she let go the horse's head, took the coat off swiftly, and as swiftly replaced it, lining upward.

"Thank-you," she said.

She glanced over her shoulder.

"Will you lead him up and down, while I go and fetch his rug?" she said. "That kid'll be all day."

"Rather!" replied the young man, with the fervour of a child to whom a pony has been entrusted for the first time.

The girl's neat slight blue-serge figure made off for the elms and the carriages. Her back turned to the young man, the sternness left her face, and she smiled.

A blue-and-black sheep-dog, shaggy as a bear, and as big, leashed to the wheel of the buggy, began to whimper and to whine with furious ecstasy. The big dog's big soul seemed to burst within him as the Angel of the Keys drew near. He had no tail to wag, so he wagged his whole body, putting back his ears, and laughing with his heart as he lifted his joyous face to his mistress.

She rested her hand a moment on his head.

"Billy Bluff," she said. "Steady, you ass!—How can I loose you?—There!"

She eased the spring of his leash. He was off with a bound, gambolling about her like a wave of the sea.

Albert was messing about the buggy in leisurely fashion.

"Hurry, Albert!" came the deep voice.

"Yes, Miss," replied the other, more leisurely than ever.

"Bring that clothes-brush along and brush Mr. Silver's coat when you've finished fooling," she said.

Then she took the rug from the buggy and went back to Goosey Gander.

The young man in his pink shirt-sleeves, his baggy white breeches, and polo boots, was walking the old horse gravely up and down, talking to him.

His back was to the girl, and she watched him with kind eyes.

She was thinking how like he and Goosey Gander were: good big uns both, as her father would say; clean-bred, large-boned, great-hearted, quiet-mannered. But the man was just coming into his prime, while the horse was well past his.

"Hullo, Bill, old boy," said the young man in his quiet voice.

Billy answered deeply.

Silver had only come to Putnam's the night before for the first time, but he and Billy Bluff were friends already. Boy Woodburn noticed it with swift appreciation. In her young and entirely fallacious judgment there were few shrewder judges of character than Big Dog Billy.

She paused a moment, pretending to shift the rug on her arm.

The group of three before her held her eye and pleased her mind. Her face was full of beauty as she watched, the spirit peeping shyly forth.

That horse, that man, that dog, so physically remote from each other, yet spiritually akin, filled her young heart with the same sense of satisfaction as did her familiar and well-beloved Downs. She felt the goodness of them and rejoiced in it. All three were sound in body and in spirit, honest, healthy, and therefore happy as the good red earth from which they came.

Monkey Brand in a long drab coat came limping toward them, his saddle over his arm.

"Best put in, Miss," he said. "Mr. Woodburn's comin'."

The old man indeed was rolling slowly toward them, followed by the chaffing and expectant crowd to whom he paid no heed. His mouth was stuffed full of bank-notes, and he was absorbed in calculations made in a little book, and muttering to himself.

"We'd best be moving," said the girl to her companion.

She led the old horse away before the oncoming crowd.

Silver followed, with grave amusement in his face. He did not know whether he dared to laugh or not, and was too much afraid to try. The girl was aware of his embarrassment and became shy in her turn.

She led the old horse up to the buggy.

This was the tit-bit of the meeting, the last and by far the greatest event. Everybody always waited for it. For was it not the Grand Finale of the Jumping Season?

Monkey Brand stuffed his saddle away in the buggy, and pulled the harness out from beneath the seat. Then he and Albert began to harness Goosey Gander, while Boy stood at the old horse's head.

The crowd gathered round and began to chaff.

"Say, Monkey, when you get that 'orse 'ome, shall you 'ave 'im for supper?—to finish the day like?"

"They'll never get 'im 'ome. He's goin' to lay down and die when 'e strikes the road—ain't you, beauty? And I don't blame 'im neether."

"He ain't though. They won't let him. That old 'orse has got to take the washin' round when he gets back to Cuckmere this evenin'."

Goosey Gander was harnessed now.

Old Mat made slowly toward the buggy.

The crowd, which had been popping off its feu-de-joie of jokes, steadied into silence to watch the old man climb to his seat.

"Someone to see you, Mr. Woodburn," came a voice in the silence.

"Indeed," panted the old man, his heavy shoulders rising and falling. "Who's that?"

There was a movement in the crowd, which parted. At the farther end of the lane thus made, a flashy young gypsy was seen, with a somnolent old mare on a halter.

"There, Mr. Woodburn!" called the gypsy in a hoarse staccato voice. "There she is—your sort to the tick. Black Death blood. Throw you a National winner and all."

The old man cast his shrewd blue eye over the mare.

She was old and rough as the halter that adorned her drooping head; but there was no mistaking her quality any more than that her one aim in life was to go to sleep.

"Yes, she's a lady all right," said the old man.

"Black Death mare, sir," reiterated the gypsy. "Out o' Vendetta. Carry the young lady a dream."

"Might ha' done twenty year ago," muttered the trainer. He took off his hat and made a floundering rush at the mare. She never so much as winked an eye, pursuing her undeviating purpose with a steadfastness worthy of a greater cause. Old Mat grunted.

"Look her over, Boy," he said.

The girl, who loved a bargain dearly as she loved a horse, was already walking round the mare. Her father was in a complacent mood; and when he was happy he would do the romantic and foolish things the girl's soul loved.

"Like her, Boy?" the old man asked.

The girl pursued her critical survey, felt the mare's legs, looked into her mouth, lifted an eye-lid. The crowd, deeply interested, watched in silence. Utterly absorbed in the work in hand, Boy, as always, was unaware of them because she was entirely forgetful of herself.

"Yes," she said simply.

The old man turned to the gypsy.

"What ye want?" he asked.

"She's yours for a tenner, sir."

He stiffened his lips.

Boy walked sedately past her father.

"Pound a leg," she said quietly in his ear.

"Four pound," said the old man, firmly. "Cash down—and accommodation."

He rustled the bank-notes in his pocket.

The gypsy frowned, and appeared to be engaged in a portentous spiritual struggle. Then the clouds cleared suddenly.

"Done with you, sir!" he called, and hauled the old mare down the widening lane through the crowd. She came reluctantly, every inch of her resenting the necessity for motion.

Old Mat paid out five sovereigns into the other's outstretched paw.

"Four sovereigns for the mare—and a half for the halter, and a little bit o' beer-money."

The crowd cheered and the gypsy danced a jig.

"You're a gentleman, Mr. Woodburn," he cried. "Now I'll tell you somefin for yourself." He drew the old man aside and whispered in his ear, ending with an emphatic: "S'truth, sir!"

The trainer grunted sceptically.

"Now, Boy," he said. "There she is. Take charge o' your cripple."

The girl, her face alight with pleasure, took the halter of the lagging mare.

Old Mat gathered the reins and mounted to his seat. Monkey Brand took his place at his master's side. Boy got up behind, the halter in her hand.

The trainer raised his whip.

The buggy bumped over the grass, the old mare trailing behind with outstretched neck. The girl folded her arms and looked down her nose like a footman.

Silver, following on his pony, saw her face and chuckled suddenly.

This stern girl had a sense of humour after all.

Then the chaff became a cheer; and the Polefax Meeting was over.

What Old Mat called his little bit of theayter—which his irreverent daughter was wont to describe with characteristic brutality as sheer swank—was quickly over.

As soon as the buggy left the fields and bumped down into the pack-horse track which led up the shoulder of the Downs, Old Mat halted. Boy slipped down from her seat, and the old man and Monkey Brand followed more leisurely. Silver dismounted, too.

The little cavalcade wound slowly up the hill, skirting the steep side of a coombe that gathered the dusk in its huge green bowl until it brimmed with mystery.

Boy looked down into it and longed, as often before, that she had wings on which to float upon that soft and undulating sea of shadow.

Not seldom this desire was so strong upon her that she felt a certainty she had wings, wings within her which she could not spread, but of the existence of which this insurgent desire was the irrefragable witness.

The sides of the coombe were hung with beeches sheathed now in tenderest green; while from out of the emptiness beneath, the insistent and melancholy cry of lambs seemed to make the shadows quiver and touched a chord of wistfulness in the heart of the girl.

The sun was already sinking behind the smooth ramparts of the hills and rose to meet them as they climbed, peering at them over the summit through the shaggy eyebrow of the gorse.

Boy walked beside the old mare, throwing every now and then swift and surreptitious glances at her new treasure. She was fearful lest the young man leading his pony on the foot-track at her side should think her a baby and over-keen.

Once only he spoke to her, and that clearly with the difficulty of the shy.

"What shall you cuc-call her?" he asked.

"I don't know," she answered.

She longed to help him, but when the chance came she could only snub him. That was always the way with Boy, when she was in touch with somebody she liked.

Old Mat came unconsciously to the rescue.

"Why, Four Pound, o' course," he panted, labouring up the hill, his hands on his knees.

"Is she Black Death blood?" asked the young man.

"Yes, she's Black Death all right," answered the old man. "That's the old Pocahontas strain. Jumpers to a gee. You know. Look at them gray hairs at the root of her tail—and that lazy, too! sluttin' along with her nose out and her tongue a-waggin'. They're all like that, Black Deaths are. If you was to let off a bomb under her belly, she wouldn't so much as switch her tail. Couldn't be bothered. Constitutions like hoxes, too." He paused to pant. "If what that feller said was O.K., why then she's worth money, too. Only o' course it ain't. Else he wouldn't ha' said it."

On the top of the Downs, facing the wind that blew straight from the sun sinking over Newhaven into the sea, they paused to breathe. Beneath them stretched the Weald, and the great saucer of Pevensey Bay ringed about with a line of brown sand fringed with foam. Northward was Crowborough Beacon, the Ashdown Forest Ridge, and the hills about Battle Abbey. Southward, and the way of the setting sun, the Downs ran out in huge spurs, line behind line of them, into the shining splendour of the sea, to break off abruptly in the white cliffs of the Seven Sisters. The hills were bare and bleak in their austere yet rounded strength, stripped of trees, clothed only in resplendent gorse, here a squat haystack dumped upon a ridge against the sky, there a great patch of plough let into the green.

"By Jove!" cried the young man; and the girl thrilled to him because she felt he loved what was so much to her.

"Some space," panted the old man, climbing back to his seat, and tucking the rug around him. "Room to stretch a hoss here; and somethin' for his windpipe better'n Owlbridge's lung-tonic."

Boy said nothing but stood breathing deep and with quiet eyes. At her side was Billy Bluff, his shaggy hair blown back from his forehead and astrew across his face, lifting his nose as though to sniff the sunset.

They jogged quietly along the crest of the hills, travelling always toward the sun, over the ancient Pilgrim's Way that runs from Pevensey, by the Holy Well in Cow Gap, and the Lamb on the hill at Eastbourne, past the Star at Alfiriston along the top of the Downs to that cathedral beyond the Arun, once a chapel of wood, whence St. Wilfrid set out to take the Gospel from the coast to the heathen dwelling in the dark and savage Andred's Weald.

The slope was with them; and Goosey Gander made his own pace, slipping along with smooth and easy stride.

They followed the line of the telegraph poles, skirting steep coombes shrouded at the foot with beech woods, past round-eyed dew-ponds, at which cloaked shepherds were watering their flocks. Once an encampment in the gorse caught their eyes. A yellow van, an ancient horse or two hobbled in the gorse-bushes, a patch of brown tent, and a whiff of blue smoke rising from an unseen fire, betrayed the nature of the squatters.

The old man pointed them out with his whip.

"There they are, the beauties," he said. "Thought they wouldn't be fur. Rogues and rasqueals, Mr. Silver!" he cried, twiddling his whip, and raising his voice to a sort of chant. "Rogues and rasqueals on h'every side, layin' in wait for to take a little bit off you—same as the Psalmist says. And it's no good talkin' to 'em. None whatebber." He dropped his voice to the old confidential note. "Pinch the hair off the back o' your head while you're sleepin', they would. Wonder who they sneaked her off?"

He turned his rogue-eye on the young man on the chestnut pony jogging at his side, winked, and made a movement with his elbow.

"Course if they was to claim her, I got her off of an old friend o' mine down in the West Country," he said, raising his voice. "Better still Ireland as further away. Yes, South of Ireland—a'ter Punchestown. He'd better be dead, too, my old friend—so he can't tell no tales and deny no stories." He elaborated his idea with glee, clapping his sides with his elbows. "Yes, that's about it. I bought her in at the sale of the effects of an old friend o' mine, South of Ireland—to help his widie. That's got it. Good idee. Very good idee. Charity and business—what they like. Micky Mahon, his name was. Died o'—I must have it all pat on the tongue. What did he die of, Brand? You're an artful little feller, settin' there so smug and secret like a hen crocodile a-hatchin' h'out h'its h'egg."

"Lung-trouble's best, sir," replied the little jockey gravely. "I reck'n you can't go far with lung-trouble. See, we all dies o' shortness o' breath in the latter end. That is lung-trouble in a manner o' speakin'."

"Lung-trouble's good," said the old man. "Vairy good. You're a good little lad, Brand. You help me in my hour o' need...."

"Father!" came the stern voice from the back seat.

The old man began to flap with his elbows.

"There she goes, givin' tongue! Is that you, Miss?" he called, in his half-humorous whimper. "You wasn't meant to hear that. Your ears is altogether too long—like that young Lollypop hoss o' mine."

They swung away off the crest of the Downs and began to drop down the slope into the village of Cuckmere lying beneath them in the valley among trees.

The sun dipped into the sea as they turned with a noise of grinding wheels into the village street. The news of Goosey Gander's victory had preceded them and they drove slowly through little crowds of cheering children, between old flint cottages with tiled roofs, and gardens white with arabis and overspread with fig-trees.

As they turned a corner, Putnam's lay before them, a Queen Anne manor-house, homely, solid, snug, with low blue parapeted roof, standing a little back from the road, and buttressed by barns and stable-buildings.

Directly they came in sight of the windows of the farm the old man took his hat off his shining head, put it on the end of his whip, and began to twiddle it.

The signal was instantly answered.

A handkerchief was waved at a lower window.

"There's Mar!" Mat said comfortably, easing into a walk. "One thing, she ain't dead. That's a little bit o' better."

He gave his plump body a half-turn and began again to whimper over his shoulder to the occupant of the back seat.

"You wouldn't get your old dad into trouble, would you then, Boy?—not by tellin' Mar I done a lot o' things I never dreamed o' doin'. If you was to say I betted now you'd say what wasn't true, wouldn't you?—and you've often told me what come to Annie Nyas and Sophia in the Book, haven't you? A lesson to us all that was—to be took to 'eart, as the sayin' is. All I done was just this: An old friend come up to me—had a drop in him, must have had!—and he says: 'Your old hoss won't win, Mat,' he says, very insultifyin'. 'My old hoss will win then,' I answers, polite as you please. 'De we,' I says, mindful o' Mar. 'Will you back your opinion?' says he, sneery. 'No,' I says, very firm. 'No; I never bets—cause o' you know.' 'Oh, yes,' he says, 'I know you—and I know your master,' meaning Mar." He swung round and addressed the young man riding on his right. "That's 'ow they go on at me all the time, Mr. Silver," he whined. "Persecute me somethin' shockin' because o' me religion—for all the world as if I could help it."

"It's not your religion," came the deep voice from the back seat. "It's mother's."

"What's it matter whose religion it is if they martyrizes you for it at the stake?" wheezed the old man. He took up his tale anew. "So as I was sayin' he says to me, Sam Buckland do: 'Man to man,' he says, 'I respeck you for stickin' to principles what you don't 'old, Mat,' he says. 'And far be it from me to undermine a man's faith what he learned acrost his mother's knee,' he says. 'But see here,' he says; 'if that 'ole rockin'-hoss o' yours gets round the course I'll give you fi' pun for yourself; if a miracle happens and he gets a place I'll make it a tenner; and if all the other hosses takes and lays down and dies so as he wins outright, it's a pony to you.' And I says to him: 'As to my champion, Mr. Buckland,' I says, 'you're jealous of him and I don't blame you, seein' as he can roll faster nor any hoss o' yours can gallip. But if he don't win,' I says, 'I'll give you fi' pun to buy yourself some manners with, fi' pun for your missus to get her a better 'usband, and fi' pun for that bald-faced, ewe-knecked, calf-kneed son of a laughin' jack-ass who calls you dad.' That's all that happened' Boy. That's not bettin', is it? That's fair give-and-take. Quite a different thing entirely. Ask the clergee."

They pulled up in the road.

Mrs. Woodburn came slowly down the steps of the old manor-house to meet them.

She was a tall woman, gray, rather gaunt, and perhaps twenty years younger than her husband. She wore a plain black dress, and there was about her a wonderful atmosphere of peace and dignity.

Nobody but Mat would have dreamed of calling such a woman Mar, and any other woman of the type but Patience Longstaffe would have resented the name.

"I'm glad you won, dad," she said in a voice deep as her daughter's, but harsher, as though from wear. "And I hope you won fair."

The old man, who had alighted, was passing the reins through the rings of the saddle.

"There she goes!" he croaked in his protesting voice. "Might just as well be on the crook—straight, I might, for all the credit I gets."

Mrs. Woodburn kissed him and the girl, and ran a practised eye and hand down Goosey Gander's fore-legs.

His wife might be a Puritan, but Mat was the first to admit that there was little about a horse he could teach her.

"He got round all right, then, Brand?" she said.

"Oh, yes, 'm," chirruped the little jockey. "It was light goin', so his pipe didn't trouble him; and he fenced like he was in Paridise. I lay off a bit till they was all bust, then I come right away through 'em and spread-eagled the lot."

The woman's hand, strong yet tender, passed down the old horse's flank.

"I see you waled him," she said.

"Well, 'm, just a couple of taps like—to settle it," deprecated the other. "Three fences from home I see I'd got the measure of 'em, and come away from the ruck with a rattle. Then I easied him home."

"You'd no call to take up your whip, Brand," grumbled the old man. "He'd ha' won without that, and you'd a plenty in hand."

"I told him to come through and finish it if he got a chance," interposed Boy from the back.

The old man turned away with a grunt.

"Oh, you told him, did you? Course my instructions goes for nothin' if you told him. There's two masters in my stable, Mr. Silver, as you see—and neither of 'em's me."

"Mother!" called the girl.

Mrs. Woodburn went round and looked at the old mare.

"What d'you think of her?" asked Boy, unable to disguise her keenness.

"You've bought two," said the mother slowly.

"D'you think so?" cried the girl.

"Sure," muttered the old man. "One thing, if they claim her, they can't claim her foal, too." He grunted in his wife's ear: "Chap said she's in foal to Berserker. Likely tale, ain't it? Howsoebber, if 'tain't true, don't make no matter; if 'tis, all the better. Anyways, she might throw a winner, plea' Gob in his goodness."

Mrs. Woodburn held up a warning finger at him.

"Now, dad!" she said; then turned to her daughter.

"Turn her out in the Paddock Close for the present," she said. "And send one of the lads for Mr. Silver's pony."

The girl led the old mare away into the yard. Jim Silver followed slowly.

In the days when Putnam's had been a farm, the yard had always been deep in dung and litter. Now it was cobbled and clean as a kitchen floor. All round it on three sides were old barns and cattle-sheds, transformed into rough but roomy loose-boxes. And the most casual observer could not have mistaken the nature of the place. For a clock stood above the main building; a chestnut crib-biter, looking out into the yard, had the top of his half door between his teeth and was wind-sucking with arched neck; while a flock of fan-tails strutted to and fro, flirting and foraging.

A tortoise-shell cat crossed the yard leisurely. The cat was known as Maudie. But it was a matter of dispute amongst those interested in the question whether she derived her name from Maud Allan, the dancer, or from Mordecai, the Jew. The dispute hung round the question whether Old Mat had christened her or Ma. If she owed her name to Old Mat, then it was clear that it came from the dancer; if to Ma, then from the Old Testament.

Billy Bluff, entering the yard in an expectant bustle, made for Maudie with a joyful flourish. Maudie arched her back, spat, and passed on gingerly. Whenever the pair met, and that was frequently, they went through the same pantomime, to the satisfaction of one of them at least.

The bob-tail next made a dash at the fan-tails. These rose with a mighty splashing of wings, fluttered a yard above his head, and settled again unconcernedly.

Albert, who, true to his promise, had somehow got home before the rest of the party, was standing outside the door of the saddle-room. The other lads were gathered round him in respectful silence. Albert was busy, but he was not engaged as usual in telling his admirers tall stories of the Meeting and his own prowess in getting the blind side of mugs and dandy duds. He had a bit of chalk in his hand and was drawing on the door. There was no doubt the lad could draw. Monkey Brand indeed asserted that there were few things Albert Eddud could not do if he tried—"and the wusser the thing the better he does it." Now he was drawing the head of a man with a huge and bulbous nose. Boy caught a glimpse of it as she entered the yard, and recognised it in a flash. It was the face of the hero of a comic paper the lads took in: a paper of which she disapproved, although with her instinctive sense for government, she did not think it wise to suppress it. Ally Sloper its name; its subject, ladies in bathing costume.

Albert, rapt in his labour, was working with the fury of the artist. He finished with a flourish. The lads crowded round to look. Foremost amongst them were Jerry, a youth with corrugated brow and profoundly sagacious air; and Stanley, dark and sleek and heavy of face, in whom sloth and sleep and insolence seemed to war. Jerry clearly should have been a philosopher, and Stanley an emperor.

Monkey Brand was in the habit of referring, not without bitterness, to the pair and Albert as "them three." He believed them capable of anything, and was not far out in his belief. Jerry, the thinker, planned the crimes; Albert, the man of action, committed them; and Stanley, the stupid, bore the blame and paid the price. When they were not at each other's throats, the three hung very close together.

Albert Edward now thrust his friends aside.

"Half a mo'!" he cried, and scrawled in dashing hand beneath the portrait the legend:

Ally Slo's

Got a nose

Like our Jose'.

S.

Albert stood back with folded arms to admire his masterpiece. The beauty of it over-awed his naturally irreverent spirit.

"'Ush!" he said.

But a rude voice burst in on his silent rapture.

"Albert!" it called peremptorily.

The artist turned round to see Boy leading the old mare into the yard.

"Yes, Miss."

"Take Mr. Silver's pony."

"Yes, Miss."

"Jerry, put Billy Bluff on the chain. Stanley, put that chestnut's muzzle on."

She led the old mare to the gate that opened on the Paddock Close.

Silver followed her, and looking back saw Monkey Brand limp into the yard from the road, leading Goosey Gander.

Mat was on the other side of the old horse, walking thoughtfully, his whip over his shoulder, and muttering to himself, as was his way.

Goosey Gander's head was framed fittingly between master and man. Now he rubbed it against one and now against the other. They led him to the water-trough and stood over him as he drank with nibbling lips, shaking the oppressive collar from his shoulders. Jim Silver at the gate watched the little group with quiet content. The three seemed so perfectly at home together that between them was no need for words.

Monkey Brand was a cockney.

He had been born in the River Ward of Hammersmith in that blind alley known to the police and the inhabitants as Tiger Bay.

His father's ice-cream business never had any fascination for the lad; but from the first his spirit drew him to the long-eared shaggy mokes of certain of the neighbours. While the other urchins from the River Ward spent their days in and out of the river dodging the coppers, at the draw-docks on Chiswick Mall, or down by the coal-wharves under the bridge, Monkey's happiest hours were passed leading a coster's cart laden with green stuff up and down the alleys. When possible he slept with Mary, the donkey he had in charge. She was fond of him, too; and the Joes, who owned her, found that the long-eared lady, when in one of her stubborn moods, would give to the boy's persuasions what she refused to the big stick.

To the Joes Monkey proved himself invaluable.

He was industrious and reliable; and he had his reward when young Joe jaunted across London for fish at Billingsgate or greens at Covent Garden and took the lad with him.

The great day of the boy's life came when the Joes took him to Epsom for the Derby week.

Old Joe, young Joe's missus, and the kids, stowed away in the body of the cart; while young Joe balanced on one shaft and Monkey on the other. The party crossed Barnes Common in the small hours of the Monday morning, and dossed on Banstead Downs that night. Next day they joined the great stream of traffic rolling out of London Epsomward. Young Joe, whose strength lay in his powers of sympathetic intuition, let Monkey drive. And the urchin took his place with pride in that vast stream of char-à-bancs, 'buses, hansoms, and drags rolling southward; and no four-in-hand coachman of them all held up his hand to stay the following traffic, or twiddled his whip with lordlier dignity than the dark lad who sat on the shaft and drove Mary up the hill on to the course.

There for the first time young Monkey saw thoroughbred horses. They were a revelation to the lad. He stood and gaped at their beauty.

"Don't 'alf shine neever!" he gasped. "I reck'n our Mary couldn't 'old 'em."

At the end of the week the Joes returned to Tiger Bay without their coachman.

"Where's my Monkey then?" cried his mother.

"Stayed along o' the 'orses," young Joe answered, unharnessing.

Indeed there was but one walk in life for which the boy was fitted; and the fates had guided him into it young.

It was when he was nineteen that Mat Woodburn found him out.

Monkey had been left at the post in a steeplechase. Old Mat didn't follow the race. Instead he watched the struggle between the lad and the young horse he was riding. Monkey gave a masterly exhibition of patience and tact; and Mat, then in his prime and always on the look-out for riding talent, watched it with grunts of pleasure. Monkey won the battle and went sailing after the field he could not hope to catch, cantering in long after the other horses had got home and gone to bed, as his indignant owner expressed it.

"Fancy turn!" he said. "Very pretty at Islington. You don't ride for me no more."

"Very good, sir," said Monkey, quite unperturbed.

As he left the dressing-room Mat met him.

"Lost your job, ain't you?" he said. "Care to come to me? I'm Mat Woodburn."

Monkey grinned.

"I know you, sir," he said. "Yes, sir. Thank you. I'm there."

Thus began that curious partnership between the two men which had endured twenty-five years.

Always master and man, the two had been singularly intimate from the start, and increasingly so. Both had that elemental quality, somewhat remote from civilization and its standards, which you find amongst those who consort greatly with horses and cattle. Both were simple and astonishingly shrewd. They loved a horse and understood him as did few: they loved a rogue and were the match for most.

Both had a wide knowledge of human nature, especially on its seamy side, based on a profound experience of life.

Monkey Brand had never been quite in the front rank of cross-country riders. At no time had he emerged from the position of head-lad, nor apparently had he wished to do so. It may be that he lacked ambition, or was aware of his limitations. For his critics said that, consummate horseman though he was, he lacked the strength to hold his own consistently in the first flight. Moreover, just at the one period of his career when it had seemed to the knowing that he might soar, the brilliant Chukkers, then but a lad, had crossed the Atlantic in the train of Ikey Aaronsohnn—to aid the cosmopolitan banker to achieve the end which was to become his consuming life-passion; and in a brief while had eclipsed absolutely and forever all his professional rivals.

Silver opened the gate into the Paddock Close. Boy passed through, leading the old mare.

"Shall I take her?" asked the young man.

"No, thank you," she answered.

In the depths of her eyes there lurked a fugitive twinkle. So far the intercourse between herself and Mr. Silver had consisted in his offering to do things for her and in her refusing his offers.

The Paddock Close stretched away before the girl in the evening light. On the hill half-a-dozen young horses stampeded in the dusk.

An early swift screeched and swept above her. A great white owl swooped out of the wood and waved away up the hillside, hovering over the gorse. Under the hedge a scattered troop of children were coming down the slope along the path that led past the little old church among the sycamores.

Boy led the mare up the hillside, her eyes on the flowing green of the hill. The young man followed in her wake, lazy almost as the old mare, who trailed reluctantly behind with clicking shoes. The dreams seemed to have possessed him, too. He did not speak; his eyes were downward; but he was aware all the time of that slight, slow-moving figure walking just in front of him.

Then something seemed to disturb the stillness and ruffle his brooding mind. It was a vague disease as of a coming sickness, and little more. He emerged from the land of quiet and looked about him, like a stag disturbed by a stalker while grazing.

A man was blundering down the hillside toward them, an easel on his shoulder.

As he came closer his face seemed strangely familiar to the young man. Where had he seen it? Then he recollected in a flash. It was the face Albert had drawn in caricature on the stable-door—the face of Ally Sloper.

Silver found himself wondering whether the owner of the face was aware of his likeness, crude indeed though real, of his great protagonist.

The fellow was incredibly slovenly. His hair was reddish and bushy about the jaw, and but for his eyes you might have mistaken him for a commonplace tramp. Those eyes held you. They were sensitive, suffering, terrible with the terror of a baffled spirit seeking escape and finding none. In that coarse and bloated face they seemed pitifully out of place and crying continually to be released. Indeed, there was something volcanic about the man, as of lava on the boil and ready at any moment to pour forth in destructive torrents. And surely there had been eruptions in the past with fatal consequences.

Now he waddled toward them with an unsavoury grin.

"What luck?" he called, in a somewhat honied voice.

"We won," replied Boy briefly.

She slipped the halter over the head of the old mare, who, too lazy to remove herself, began to graze where she stood.

The artist stood above the girl, showing his broken and dirty teeth, his eyes devouring her.

Silver resented the familiarity of his gaze.

"Mr. Silver, this is Mr. Joses," said the girl.

The difference between the two men amused her: the one clean, keen, beautifully appointed, like a horse got up for a show, the other shaggy and sloppy as a farmyard beast.

"Very pleased to make your acquaintance, sir, I'm sure," grinned the artist, bowing elaborately.

The other responded coldly.

Joses had not made a favourable impression on the young man. Boy saw that at once; and it was not difficult to see. For Silver showed his likes and dislikes much as Billy Bluff did.

The girl wished with all her heart that she was standing behind him that she might see if the hair on the back of his neck had risen.

A spirit of mischief overcame her.

"Mr. Joses'll paint your horses for you," she said demurely.

"Delighted, I'm sure," laughed the artist.

"Thank you," said the young man, with a brevity the girl herself could not have surpassed. His shyness had left him, and with it his tendency to stammer.

Boy felt herself snubbed, and was nettled accordingly.

"I'm going home by the wood," she said.

"I'll come with you," said the artist.

The two moved away down the hill together toward the wood that thrust like a spear into the heart of the Paddock Close.

Silver watched them with steady eyes. As usual he had been left. That swift and slimy artist-chap had chipped in while he was thinking what he should do.

Silver hated artists—not as the result of experience, for he had never met one in the flesh before, but from instinct, conviction, and knowledge of the race acquired from books. Artists and poets: they were all alike—dirty beggars, all manners and no morals, who could talk the hind-leg off a she-ass.

And Silver, being dumb himself and very human, hated men who were articulate.

He watched the pair walking away from him down the hillside. An ill-matched couple they seemed to him: the slight, strenuous girl, her plait of hair like a spear of gold between her shoulders, her slim black legs, and air of a cold flame; and that loose, fat thing who gave the young man the impression of a suet pudding that had taken to drink.

The beast seemed disgustingly fatherly, too, rubbing shoulders with the girl, and fawning on her.

Silver sat down on a log and took out the cigarette-case, which was his habitual comforter.

The old mare grazed beside him in the dusk, and he began to laugh as he looked at her. Her laziness tickled and appealed to him. There was something great about it. She was indolent as was Nature, and for the same reason—that she was aware of immense reserves of power on which she could fall back at any moment.

A rabbit came out of the gorse to feed near by. The owl whooped and swooped and hovered behind her. The sea wind, fresh and crisp, came blowing up the valley; and the young stock, bursting with the ecstasy of life, thundered by in the dusk with downward heads and arched backs and far-flung heels.

Silver sat and smoked.

There was a funny feeling at his heart.

Some vast, deep, silent-running river of Life, of whose presence within him he had only become aware within the last few hours, had been thwarted for the moment, thrust back upon itself, and was tugging and tuzzling within him as it sought to pursue its majestic way toward the Open Sea.

Joses had been haunting the village off and on for some time past.

Boy Woodburn knew nothing of him except that Monkey Brand disliked him.

Herself she had been given no chance of forming an opinion till lately, when Joses had asked permission of her father to paint some of the horses. Old Mat had given leave, and Joses had gained the entrée to the stables. He had made the most of his chance, haunting the yard, dogged by Monkey Brand, who resented his presence, watched him jealously, and made things as uncomfortable and precarious for the artist as he could. Joses, to do him justice, stuck to his self-imposed task with astonishing pertinacity in spite of opposition. He did not give up indeed until Flaminetta, a lengthy mare with an astonishing reach, suddenly exploded without warning and missed his head with a steel-shod heel by a short foot.

Joses tumbled backward off his stool and crawled out of danger on his hands and knees with astonishing alacrity for so gross a man.

Monkey Brand, an interested witness of the catastrophe, came limping up full of the tenderest solicitude.

"Oh, my, Mr. Joses!—my!" he cried. "I never knew her to do that afore. Ah, yer! what ye up to?"

Joses, still on his hands and knees, looked up at the little jockey, his eyes aghast with anger and fear.

"Ginger!" he snorted. "You put it there."

Monkey Brand eyed him with bland interest.

"You know a wunnerful deal about 'orses for a hartist, Mr. Joses," he remarked, not troubling to deny the soft impeachment.

Joses got to his feet and began to talk volubly.

Monkey Brand listened in respectful silence, waving to the lads to keep in the background.

When the orator had finished, the little jockey went in to report to Old Mat.

"He knows altogether too much that Mr. Joses do," he ended.

The trainer nodded.

"I guessed as much," he said. "I'll make inquiries."

Two days later Old Mat called his head-lad into the office. He was in his socks and shut the door with precautions.

Mystery was the breath of life to both men, who were at heart but children.

"Seen Joses lately?" began the old man cautiously.

"Not since then, sir," the other answered in the same tone.

Old Mat went to the window and drew down the blind. There was nobody but Maudie in the yard outside, and no human being within fifty yards. But such considerations must not come between the principal actors and the correct ritual for such occasions.

"I was over at Lewes yesterday," he panted huskily. "I see that tall inspector chap—him I put on to Flaminetta for the Sefton."

Monkey was all alert.

"What did he say, sir?"

"Not much," muttered the other. "Enough, though."

Monkey drooped his eyelids and tilted his chin. His face became a masterpiece of secrecy and cunning.

Old Mat turned his lips inward.

"I've warned him off," he said, "you might snout about a bit and rout out what he is after."

The other nodded.

"Monkey's the man, sir," he said, and stole away on tip-toe.

That evening the old trainer, driving through the village, came on the discomfited artist and drew up to have a word with him.

"Oh, dear! Oh, dear! Oh, dear!" began the old man in his sympathetic wheeze. "This is a bad job to be sure, Mr. Joses. So that long mare o' mine had a shot at your pore brain-box. When I heard, I wep' a tear, I did reelly." He shook a sorrowful head. "You mustn't come no more, though, Mr. Joses, you mustn't. If anything was to 'appen to you in my place I should never forgive meself. 'Tain't so much the compensation to your widows and such. It's here"—he thumped his heart—"I'd feel it."

Joses began to make excuse, but the old man refused to be convinced.

"Rogues and rasqueals, Mr. Joses," he cried. "Layin' pitchforks for yer feet—same as the Psalmist says. Hosses is much the very same as men. Kilted cattle, as the sayin' is. Once they turn agin' you your number's up. And they got somefin' agin' you. No fault o' yours, I know—godly genelman like you. But where it is there it is!" He sat in his buggy and wiped his dewy eye. "And there's the dorg, Mr. Joses. Big dorg, too!"

Joses, ejected from Putnam's, as Adam had been from Paradise, might be the loser; but Art certainly was not.

For he painted abominably.

Even the lads jeered at his efforts, while Old Mat said:

"I reck'n my old pony could do better than that, if I filled her tail with paint and she sat on it."

But Joses was not to be beaten so easily. Meeting Boy Woodburn in the village street, he asked her if he might paint Billy Bluff.

The girl, knowing Billy's views on Mr. Joses, excused herself and her dog.

Joses walked down the village street with her, expostulating.

Mrs. Haggard, the vicar's wife, an austere woman, with a jealously guardian eye for all the village maidens, met the pair and eyed the girl severely.

Later in the day she came on Boy alone and stopped her.

"Do you know that man, Joyce?" she asked.

Mrs. Haggard was the one person in the world who called Boy by her Christian name. And she did it, as she did everything else, on principle.

"Not really," answered Boy.

"I don't like him," said Mrs. Haggard.

"Neither do I," answered the girl.

"I'm glad to hear it," said the other. "He's not a nice man."

That evening Mrs. Haggard went to see Mrs. Woodburn and gave the trainer's wife some of her reasons—and they were good reasons, too—for thinking Mr. Joses not a nice man.

Mrs. Woodburn, who was in the judgment of the vicar's wife a good but curious woman, showed herself distressingly undistressed.

"Boy can look after herself, I guess," she said, a thought grimly.

She reported later to Mat what Mrs. Haggard had told her and what she had replied to Mrs. Haggard.

Old Mat agreed.

"She can bite all right," he said. "Trust Boy."

And Boy, as she walked down the hillside on leaving Mr. Silver and the old mare, felt like biting.

She was annoyed with Mr. Silver, annoyed with Joses, and, above all, annoyed with herself.

She had been mischievous, and now she was being punished for it.

She did not like Joses; and she did like being alone in the wood at dusk.

Her companion walked too close to her; he laughed too much; she was aware of that haunted and haunting eye of his rolling at her continually; and he smelt of alcohol.

Also he would talk.

"That's Silver, is it?" he said familiarly, as they walked down the hill.

"That's Mr. Silver," she retorted.

His eye sought hers, questioning; but found nothing save a proud, cold face.

"Your dadda's training for him, isn't he?" continued the fat man.

Her dadda!

The cheek of it!

"I don't know."

"He's a Croesus, isn't he?"

"He's not a greaser," with warmth.

Joses laughed his unpleasant laughter.

"A Croesus, I said. Rolling. He's the Bank of Brazil and Uruguay."

"I don't know," replied the girl. "I haven't asked."

They had reached the stile into the wood.

"Good-night," she said.

"I'll see you through the wood," the other answered.

A moment she hesitated. Should she after all go back by the field? If she did he would think she was afraid. And she was not, as she would show him. But she wished that Billy Bluff was with her. Reluctantly at length she climbed the stile and walked through the dusk. He shambled at her side.

"Begun to bathe yet?" he asked.

"No."

"You let me know when you begin, and I'll come and paint you on the rocks."

Her eyes flashed up at his.

"You won't!" she said fiercely.

He edged in upon her, laughing sleekly.

"Saucy, is it?" he said.

"Keep off!" she cried.

"Wants taming, does it?"

He wound his arm about her.

"Let me go!"

She kicked his shins with her square-toed shoes.

She kicked hard and hurt him.

"You little devil!" he snorted.

He pressed her to him, seeming to smother her, like an offensive blanket.

His red beard brushed her forehead; his hot face crowded down on hers; and above all his great red nose protruded above her like an inflamed banana.

Mrs. Haggard was fond of saying that Joyce Woodburn was like a wild animal. And in a way the vicar's wife was right. Self-preservation was the first law of life for the girl as for every healthy young creature. And long and intimate contact with horses and dogs had made her swift and direct in action as were they.

Now when she felt herself in the clutches of the Beast, and the Greater Death closing in upon her, she knew as little of doubts and scruples as any creature of the wilderness.

That hateful breath was in her nostrils; those covetous eyes were close to hers; that inflamed and evil nose protruded over her in flaming invitation.

She seized it in her gloved hand and wrenched it. The effect was immediate.

Joses squealed and clapped both hands to his damaged organ.

"My——, you——!" he squeaked in the voice of a Punch.

The girl broke away and ran. She was swift and hard as a greyhound. For a moment the other stood, leaning over a bed of nettles, snorting and sniffing as the blood dripped from his nose. Then he pursued. She heard him thundering behind her. It was like the pursuit of a fawn by a grizzly. She had only a hundred yards to go to the open; and as she fled with her head on her shoulder, and her plait flapping, feeling the strength in her limbs and the courage in her heart, she mocked her pursuer silently.

That drink-sodden grampus catch her!

Her pride came toppling down about her. She tripped, wrenched her ankle, and knew that she was done.

Before her was a familiar tree she had often climbed, with a branch some six feet from the ground.

She swung herself up.

The Great Beast came snorting up. He was a dreadful sight. His nose was bleeding profusely, and the blood had mingled with his beard and moustache. He had lost his cap, and his head shimmered bald at her feet beneath wisps of hair.

He seemed like a great vat full of spirit into which she had tossed a lighted match.

"I got you, my beauty!" he panted in smothered and unnatural voice.

He put his hands on the branch.

She stamped on them with her heels: and she stamped hard. He swore, and drew from a leather sheath a wooden-handled knife such as Danish fisher-folk use.

She grasped the branch above her and swung in the air; but she could not swing forever thus.

"I can wait," said the Great Beast beneath, laughing dreadfully.

Then there came the sound of a man singing some kind of boating-song.

The voice was deep and drawing nearer.

"Then we'll all swing together,

Steady from stroke to bow."

It was Silver strolling home through the wood.

Boy heard him; so did Joses, and withdrew into the dusk.

The girl slipped down from the tree.

The young man dawdled up, and looked at her with some surprise.

"Anything up?" he asked.

"Yes," said Boy. "Up a tree."

She limped coldly away.

He followed her.

"Are you lul-lame?" he asked, shy and anxious.

"Sprained my off-hind fetlock," she replied.

Patience Longstaffe was the only child of Preacher Joe, of God-First Farm, on the way to Lewes; and she was very like her father.

He had been brought up a Primitive Methodist and had first heard the Word at Rehoboth, the little red brick place of worship of the sect on the outskirts of Polefax; but being strong as he was original he had seceded from the church of his fathers early in life to the Foundation Methodists and started a little chapel of his own, which bore on its red side the inscription that gave the popular name to its founder's farm.

The chapel was hidden away down a lane; but as you drove in to Lewes along the old coach-road, with the Downs bearing on your left shoulder, you could not mistake Mr. Longstaffe's farm: for a black barn on the roadside carried in huge letters the text,

Seek ye first the Kingdom of God.

To the cultivated and academic mind there might be something blatant and vulgar about so loud an invitation.

But if its character estranged the carriage-folk, the man who had put it up had sought the Kingdom himself, and had, if all was true, found it. Joe Longstaffe was by common consent a Christian man, and not of that too general kind which excuses its foolishness and fatuity on the ground of its religion. The Duke's agent disliked him for political reasons, but he would admit that the dissenter was the best farmer in the countryside; and the labourers would have added that he was also the best employer.

The curious who walked over from Lewes to attend the little chapel in which he held forth, found nothing remarkable in the big, gaunt man with the Newgate fringe and clean-shaven lips, who looked like a Scot but was Sussex born and bred. Joe Longstaffe was not intellectual; his theology was such that even the Salvation Army shook their heads over it; he had read nothing but the Bible and Wesley's Diary—and those with pain; he stuttered and stumbled grotesquely in his speech, and a clerical Oxford don, who pilgrimaged from Pevensey to hear him, remarked that the only thing he brought away from the meeting was the phrase, reiterated ad nauseam,

"As I was sayin', as you might say."

But there was one mark-worthy point about the congregation of the chapel; and the Duke in his shrewd way was the first to note it.

"Nine out of ten of the people who attend are his own folk—his carters, shepherds, milk-maids, and the like. And they don't go for what they can get. Now if I started a chapel—as I'm thinkin' of doin'—d'you think my people'd come? Yes; if they thought they'd get the sack if they didn't."

They went, indeed, these humble folk, because they couldn't help it. And they couldn't help it because there was a man in that chapel who drew them as surely as the North Pole draws the magnetic needle. And he drew them because there was Something in him that would not be denied, Something that called to their tired and thirsting spirits, called and comforted. It was not possible to say what that Something was; but this man had it, and it was very rare. And that tall daughter of his, who rarely smiled, and never grieved, who was always strong, quiet, and equable, going about her work regular as the seasons, possessed it, too.

Everybody, indeed, respected Patience Longstaffe, if few loved her.

She was long past thirty, and people were beginning to say that she had dedicated herself to virginity, when to the amazement of all it was announced that she would marry Mat Woodburn, the trainer, twenty years her senior.

The Duke, of whose many failings lack of courage was not one, asked her boldly why she was doing it.

Her answer was as simple as herself.

"He's a good man," she said.

It was a new and somewhat surprising light on the character of Old Mat, but the Duke accepted it without demur.

"She's right," he said at the club at Lewes. "Mat's a rogue, but he's not a wrong 'un." And with his unequalled experience of both classes, the old peer had every right to speak.

The vulgar-minded, who make the majority of every class in every country, thought that Preacher Joe would make trouble, and looked forward hopefully to a row. For at least a month after the announcement every drawing-room and public-house in South Sussex was rife with malicious and sometimes amusing stories. The authors of them were doomed to disappointment. Not only was Mr. Longstaffe quietly and obviously happy, but he and his son-in-law, who was but five years his junior, showed themselves to be unusually good friends.

And there was no doubt the marriage was a success. The content on Patience Woodburn's face was evidence enough of that.

How far the strange and apparently ill-assorted couple affected each other it was difficult to say. Outwardly, at least, Old Mat remained Old Mat still, and Patience, although she became Ma Woodburn, went her strong, still way much as before her marriage. Bred on the land and loving it, inheriting a wonderful natural way with stock of every kind, she was from the first her husband's right hand, none the less real because unsuspected and to a great extent unseen.

She was never known to attend so much as a point-to-point, but when a colt wasn't furnishing a-right, or a horse entered for a big event was not coming on as he should, it was Ma who was sent for and Ma who took the matter in hand.

"I've nothing against horses and racing," she would say. "God meant 'em to race and jump, I reck'n. But I don't think he meant us to bet and beer over 'em."

From the first she was a power in the Putnam stable.

Except in a crisis she interfered little with the lads, but when they went sick or smashed themselves, she took them into her house and nursed them as though they were her own. If they were grateful they did not show it; but in times of stress some spirit whose presence you would never have suspected made itself suddenly and sweetly apparent.

The Bible Class for the lads in her husband's employ she had started on the first Sunday of her reign at Putnam's.

It was voluntary for those over fifteen; but all the lads attended—"to oblige."

That class at the start had been the subject of untold jokes in the racing world.

There had even been witticisms about it in the Pink Un and other sporting papers.

And when Mat had been asked what he thought of it the story went that he had answered:

"I winks at ut," adding, with a twinkle: "I winks at a lot—got to now."

Ma Woodburn kept the class going for twenty years, until, indeed, her daughter was old enough to take it over from her.

Boy Woodburn had been born to the apparently incongruous couple some years after their marriage.

From the very beginning she had always been Boy. Mrs. Haggard, who didn't quite approve of the name—and there were many things Mrs. Haggard didn't quite approve of—once inquired the origin of it.

"I think it came," answered Mrs. Woodburn.

And certainly nobody but the vicar's wife ever thought or spoke of the girl as Joyce. She grew up in Mrs. Haggard's judgment quite uneducated. That lady, a good but somewhat officious creature, was genuinely distressed and made many protests.

The protests were invariably met by Mrs. Woodburn imperturbably as always.

"It's how my father was bred," she replied in that plain manner of hers, so plain indeed that conventional people sometimes complained of it as rude. "That's good enough for me."

Mrs. Haggard carried her complaint to her husband, the vicar.

"There was once a man called Wordsworth, I believe," was all the answer of that enigmatic creature.

"You're much of a pair, you and Mrs. Woodburn," snapped his wife as she left the room.

"My dear, you flatter me," replied the quiet vicar.

On the face of it, indeed, Mrs. Haggard had some ground for her anxiety about the girl.

Boy from the beginning was bred in the stables, lived in them, loved them.

At four she began to ride astride and had never known a side-saddle or worn a habit all her life. She took to the pigskin as a duck to water; and at seven, Monkey Brand, then in his riding prime, gave her up.

"She knows more'n me," he said, half in sorrow, half in pride, as his erstwhile pupil popped her pony over a Sussex heave-gate.

"Got wings, she have."

"Look-a-there!"

But the girl did not desert her first master. She would sit on a table in the saddle-room, swinging her legs, and shaking her fair locks as she listened bright-eyed while Monkey, busy on leather with soap and sponge, told again the familiar story of Cannibal's National.

It was on her ninth birthday that, at the conclusion of the oft-told tale, she put a solemn question:

"Monkey Brand!"

"Yes, Minie."

"Do-you-think-I-could-win-with-the National?"

"No sayin' but you might, Min."

The child's eyes became steel. She set her lips, and nodded her flaxen head with fierce determination.

She never recurred to the matter, or mentioned it to others. But from that time forth to ride the National winner became her secret ambition, dwelt upon by day, dreamed over by night, her constant companion in the saddle, nursed secretly in the heart of her heart, and growing always as she grew.

Certainly she was a Centaur if ever child was.

To the girl indeed her pony was like a dog. She groomed him, fed him, took him to be shod, and scampered over the wide-strewn Downs on him, sometimes bare-backed, sometimes on a numnah, hopping on and off him light as a bird and active as a kitten.

Mrs. Woodburn let the child go largely her own way.

"Plenty of liberty to enjoy themselves——" that was the principle she had found successful in the stockyard and the gardens, and she tried it on Boy without a tremor.