THE AMIN OF KALAA.

THE AMIN OF KALAA.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lippincott's Magazine, Volume 11, No. 26, May, 1873, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Lippincott's Magazine, Volume 11, No. 26, May, 1873 Author: Various Release Date: October 20, 2007 [EBook #23095] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LIPPINCOTT'S MAGAZINE *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873, by J. B. Lippencott & Co., in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Transcriber's Note: Minor typos have been corrected and footnotes moved to the end of the article. Table of contents has been created for the HTML version.

THE ROUMI IN KABYLIA.

OUR HOME IN THE TYROL

WILMINGTON AND ITS INDUSTRIES.

MARIE FAMETTE AND HER LOVERS.

SALMON FISHING IN CANADA.

A PRINCESS OF THULE.

AT ODDS.

PHILADELPHIA ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS.

BERRYTOWN.

OVERDUE.

QUEEN VICTORIA AS A MILLIONAIRE.

CRICKET IN AMERICA

OUR MONTHLY GOSSIP.

LITERATURE OF THE DAY.

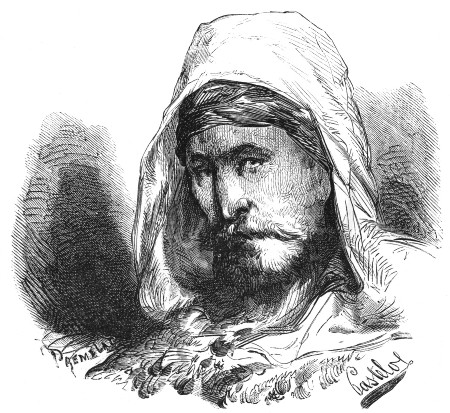

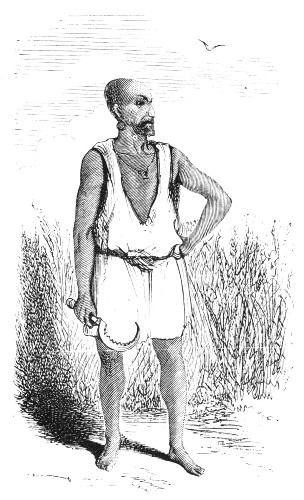

THE AMIN OF KALAA.

THE AMIN OF KALAA.

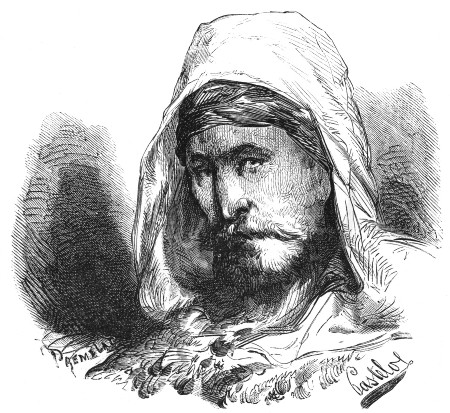

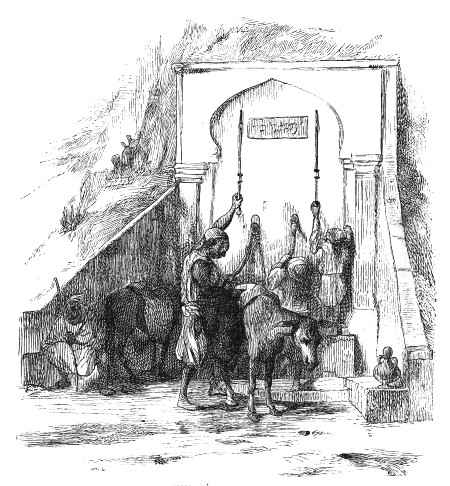

Emerging from these gloomy caflons, and passing the Beni-Mansour, the village of Thasaerth (where razors and guns are made), Arzou (full of blacksmiths), and some other towns, we enter the Beni-Aidel, where numerous white villages, wreathed with ash trees, lie crouched like nests of eggs on the summits of the primary mountains, with the [Pg 490]magnificent peaks of Atlas cut in sapphire upon the sky above them. At the back part of an amphitheatre of rocky summits, Hamet, the guide, points out a little city perched on a precipice, which is certainly the most remarkable site, outside of opera-scenery, that we have ever seen. It is Kalaa, a town of three thousand inhabitants, divided into four quarters, which contrive, in that confined situation, to be perpetually disputing with each other, although a battle would disperse the whole of [Pg 491]the tax-payers over the edges. Although apparently inaccessible but by balloon, Kalaa may be approached in passing by Bogni. It is hard to give an idea of the difficulties in climbing up from Bogni to the city, where the hardiest traveler feels vertigo in picking his way over a path often but a yard wide, with perpendiculars on either hand. Finally, after many [Pg 492]strange feelings in your head and along your spinal marrow, you thank Heaven that you are safe in Kalaa.

KALAA.

KALAA.

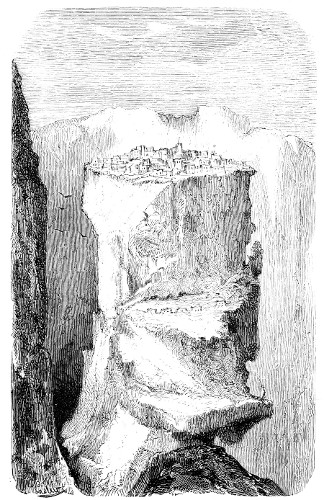

The inhabitants of Kalaa pass for rich, the women promenade without veils and covered with jewels, and the city is clean, which is rare in Kabylia. There are four amins (or sheikhs) in Kalaa, to one of whom we bear a letter of introduction. The anaya never fails, and we are received with cordiality, mixed with stateliness, by an imposing old man [Pg 493]in a white bornouse. "Enta amin?" asks the Roumi. He answers by a sign of the head, and reads our missive with care. Immediately we are made at home, but conversation languishes. He knows nothing but the pure Kabyle tongue, and cannot speak the mixed language of the coasts, called Sabir, which is the pigeon-French of Algiers and Philippeville.

COURTYARD IN KALAA.

COURTYARD IN KALAA.

"Enta sabir el arbi?"—"Knowest thou Arabic?" asks our host.

"Makach"—"No," we reply. "Enta sabir el Ingles?"—"Canst thou speak English?"

"Makach"—"Nay," answers the beautiful old sage, after which conversation naturally languishes.

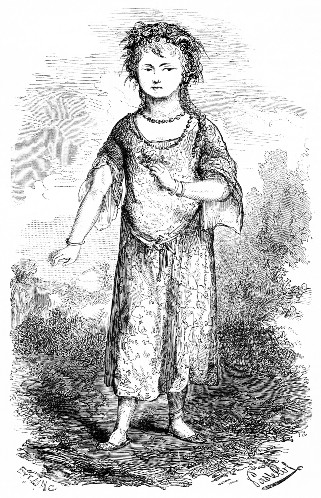

OURIDA, THE LITTLE ROSE.

OURIDA, THE LITTLE ROSE.

But the next morning, after the richest and most assiduous entertainment, we see the little daughter of the amin playing in the court, attended by a negress. The child-language is much the same in all nations, and in five minutes, in this land of the Barbarians, on this terrible rock, we are pleasing the infant with wiles learnt to please little English-speaking rogues across the Atlantic.

The amin's daughter, a child of six years, forms with her slave a perfect contrast. She is rosy and white, her mouth is laughing, her peeping eyes are laughing too. What strikes us particularly is the European air that she has, with her square chin, broad forehead, robust neck and sturdy body. A glance at her father by daylight reveals the same familiar type. Take away his Arab vestments, and he would almost pass for a brother of Heinrich Heine. His child might play among the towers of the Rhine or on the banks of the Moselle, and not seem to be outside her native country. We have here, in a strong presentment, the types which seem to connect some particular tribes of the Kabyles with the Vandal invaders, who, becoming too much enervated in a tropical climate to preserve their warlike fame or to care for retiring, amalgamated with the natives. The inhabitants on the slopes of the Djordjora, reasonably supposed to have descended from the warriors of Genseric, build houses which amaze the traveler by their utter unlikeness to Moorish edifices and their resemblance to European structures. They make bornouses which sell all over Algeria, Morocco, Tunis and Tripoli, and have factories like those of the Pisans in the Middle Ages.

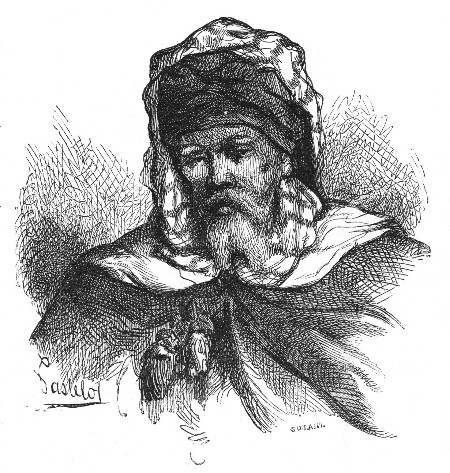

KABYLE SHOWING GERMANIC ORIGIN.

KABYLE SHOWING GERMANIC ORIGIN.

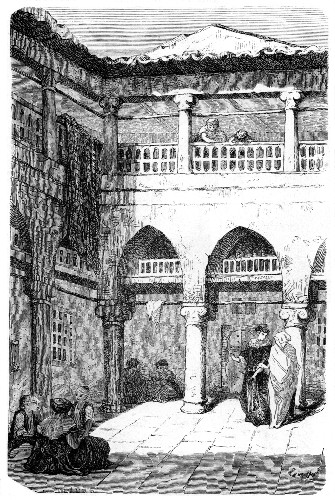

Contrast the square and stolid Kabyle head shown in the engraving on this page with the type of the Algerian Arab on page 494. The more we study them, or even rigidly compare our Arab with the amin of Kalaa, the more distinction we shall see between the Bedouin and either of his Kabyle compatriots. The amin, although rigged out as a perfect Arab, reveals the square jaw, the firm and large-cut mouth, the breadth about the temples, of the Germanic tribes: it is a head of much distinction, but it shows a large remnant of the purely animal[Pg 494] force which entered into the strength of the Vandals and distinguished the Germans of Cæsar's day. As for the Kabyle of more vulgar position, take away his haik and his bornouse, trim the points of his beard, and we have a perfect German head. Beside these we set a representative Arab head, sketched in the streets of Algiers. See the feline characteristics, the pointed, drooping moustache and chin-tuft, the extreme retrocession of the nostrils, the thin, weak and cruel mouth, the retreating forehead, the filmed eye, the ennui, the terrestrial detachment, of the Arab. He is a dandy, a creature of alternate flash and dejection, a wearer of ornaments, a man proud of his striped hood and ornamental agraffes. The Kabyle, of sturdier stuff, hands his ragged garment to his son like a tattered flag, bidding him cherish and be proud of the rents made by Roumi bayonets.

TYPE OF ALGERIAN ARAB.

TYPE OF ALGERIAN ARAB.

It must be admitted that the Kabyles, with a thousand faults, are far from the fatalism, the abuse of force and that merging of individualism which are found with the Islamite wherever he appears. Whence, then, have come these more humane tendencies, charitable customs and movements of compassion? There are respectable authorities who consider them, with emotion, as feeble gleams of the great Christian light which formerly, at its purest period, illuminated Northern Africa.

It is the opinion of some who have long been conversant with the Kabyles that the deeper you dive into their social mysteries the more traces you find of their having once been a Christian people. They observe, for instance, a set of statutes derived from their ancestors, and which, on points like suppression of thefts and murders, do not agree with the Koran. We have spoken of their name for the law—kanoun: evidently the resemblance of this to [Greek: chanôn] must be more than accidental. Another sign is the mark of the cross, tattooed on the women of many of the tribes. These fleshly inscriptions are an incarnate evidence of the Christian past of some of the Kabyles, particularly such as are probably of Vandal origin. They are found especially among the tribes of the Gouraya, are probably a result of the Vandal invasion, and consist in the mark or sign of the cross, half an inch in dimension, on their forehead, cheeks and the palms of their hands. It appears that all the natives who were found to be Christians were freed from certain taxes by their Aryan conquerors; and it was arranged that they should profess their faith by making the cross on their persons, which practice was thus universalized. The tattooing is of a beautiful blue color, and is more ornamental than the patches worn by our grandmothers.[Pg 495]

Our final inference, then, is, that the Kabyles preserve strong traces of certain primitive customs, which in certain cases are attributable to a Christian origin.

A true city of romance, a Venice isolated by waves of mountains, and built upon piles whose beams are of living crystal, Kalaa, all but inaccessible, attracts the tourist as the roc's egg attracted Aladdin's wife. For ages it has been a city of refuge, a sanctuary for person and property in a land of anarchy. Nowhere else are the proud Kabyles so skillful and industrious—nowhere else are their women so much like Western women in beauty and freedom.

KABYLE WOMEN

KABYLE WOMEN

The Kabyle woman preserves the liberty which the female of the Orient possessed in the old times, before the jealousy of Mohammed made her a bird in a cage, or, as the Arab poet says, "an attar which must not be given to the winds." In Kabylia the women talk and gossip with the men: their villages present pretty spectacles at sunset, when groups of workers and gossipers mingled are seen laughing, chatting and singing to the accompaniment of the drum. Some of these women are really handsome, and are freely decorated, even in public, with the singular enamels which are their peculiar manufacture, and with threads of gold in their graceful cheloukas or tunics.

But Kalaa, like the picturesque "Peasant's Nest" described by Cowper in his Task, pays one natural penalty for the rare beauty of its site. It pants on a rock whose gorges of lime are the seat of a perpetual thirst. In vain have the suffering natives sunk seven basins in one alley of the town, the cleft separating the quarter of the Son of David from that of the children of Jesus (Aissa). The water only trickles by drops, and, though plentiful in winter, deserts them altogether in the season when their air-hung gardens, planted in earth brought up from the plains, need it the most. As the mellowing of the season brings with it its plague of aridity, recourse is had to the river at the bottom of the ravine, the Oued-Hamadouch. Then[Pg 496] from morning to night perpendicular chains of diminutive, shrewd donkeys are seen descending and ascending the precipice with great jars slung in network.

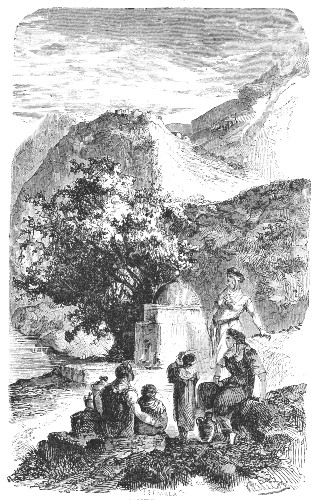

KABYLE GROUP.

KABYLE GROUP.

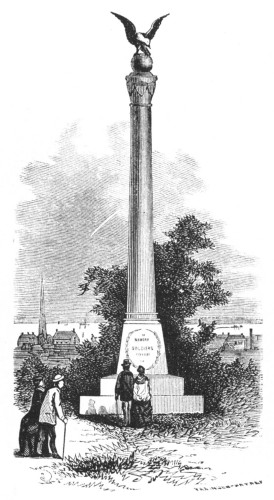

But the Hamadouch itself in the sultry season is but a thread of water, easily exhausted by the needs of a population counting three thousand mouths. Then the folks of Kalaa would die of thirst were it not for the foresight of a[Pg 497] marabout of celebrity, whom chance or miracle caused to discover a hidden spring at the bottom of the rock. By the aid of subscriptions among the rich he built a fountain over the sources of the spring.

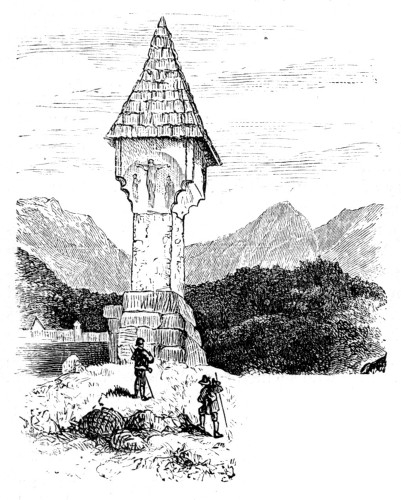

It is a small Moorish structure, with two stone pilasters supporting a pointed arch. In the centre is an inscription forbidding to the pious admirers of the marabout the use of the fountain while a drop remains in the Hamadouch. To assist their fidelity, the spring is effectually closed except when all other sources have peremptorily failed, in the united opinion of three amins (Kabyle sheikhs). When the amins give permission the chains which restrain the mechanism are taken off, and the conduits are opened by means of iron handles operating on small valves of the same metal. In the great droughts the fountain of Marabout Yusef-ben-Khouia may be seen surrounded with a throng of astute, white-nosed asses, waiting in philosophic calm amid the excitement and struggle of the attendant water-bearers.

YUSEF'S FOUNTAIN.

YUSEF'S FOUNTAIN.

Seen hence, from the base of the precipice, where abrupt pathways trace their zigzags of white lightning down the rock, and where no vegetation relieves the harsh stone, the town of Kalaa seems some accursed city in a Dantean Inferno. Seen from the peaks of Bogni, on the contrary, the nest of white houses covered with red tiles, surmounted by a glittering minaret and by the poplars which decorate the porch of the great mosque, has an aspect as graceful as unique. In a vapory distance floats off from the eye the arid and thankless country of the Beni-Abbes. On every level spot, on[Pg 498] every plateau, is detected a clinging white town, encircled with a natural wreath of trees and hedges. They are all visible one from the other, and perk up their heads apparently to signal each other in case of sudden appeal: it is by a telegraphic system from distance to distance that the Kabyles are collected for their incorrigible revolutions. Two ruined towers are pointed out, called by the Kabyles the Bull's Horns, which in 1847 poured down from their battlements a cataract of fire on Bugeaud's chasseurs d'Orléans, who climbed to take them, singing their favorite army-catch as well as they could for want of breath:

Far away, at the foot of the Azrou-n'hour, an immense peak lifting its breadth of snow-capped red into the pure azure, the populous town of Azrou is spread out over a platform almost inaccessible.

THE LATEST IMPROVED REAPER.

THE LATEST IMPROVED REAPER.

What a strange landscape! And what a race, brooding over its nests in the eagles' crags! Where on earth can be found so peculiar a people, guarding their individuality from the hoariest antiquity, and snatching the arts into the clefts of the mountains, to cover the languid races of the plains with luxuries borrowed from the clouds! The jewelry and the tissues, the bornouses and haiks, the blacksmith-work and ammunition, which fill the markets of Morocco, Tunis and the countries toward the desert, are scattered from off these crags, which Nature has forbidden to man by her very strongest prohibitions.

We are now in the midst of what is known as Grand Kabylia. The coast from Algiers eastward toward Philippeville, and the relations of some of the towns through which we have passed, may be understood from the following sketch:

The scale of distances may be imagined from the fact that it is eighty-seven and a half miles by sea from Algiers to Bougie. The country known as Grand Kabylia, or Kabylia par excellence, is that part of Algeria forming the great square whose corners are Dellys, Aumale, Setif and Bougie. Though these are fictitious and not geographical limits, they are the nearest approach that can be made to fixing the nation on a map. Besides their Grand Kabylia, the ramifications of the tribe are rooted in all the habitable parts of the Atlas Mountains between Morocco and Tunis, controlling an irregular portion of Africa which it is impossible to define. It will be seen that the country of the tribe is not deprived of seaboard nor completely mountainous. The two ports of Dellys and Bougie were their sea-cities, and gave the French infinite[Pg 499] trouble: the plain between the two is the great wheat-growing country, where the Kabyle farmer reaps a painful crop with his saw-edged sickle.

In this trapezoid the fire of rebellion never sleeps long. As we write comes the report of seven hundred French troops surrounded by ten thousand natives in the southernmost or Atlas region of Algeria. The bloody lessons of last year have not taught the Kabyle submission. It seems that his nature is quite untamable. He can die, but he is in his very marrow a republican.

"Do not go to the Tyrol," said some of our friends in Rome. "You will be starved. It is a beautiful country, but with the most wretched accommodation and the worst living in the world."

"Come to Perugia, where it is always cool in summer," said a painter. "You can study Perugino's exquisite 'Annunciation' and other gems of the Umbrian school, and thus blend Art with the relaxation of Nature."

"Come rather to Zemetz in the Engadine, where good Leonhard Wohlvend of the Lion will help us to bag bears one day and glaciers the next," exclaimed a sporting friend, the possessor of the most exuberant spirits.

SHRINE AT ADELSHEIM.

SHRINE AT ADELSHEIM.

"But," remarked the fourth adviser, a lady, "I recommend, after all, the Tyrol. I went weak and ill last year to the Pusterthal, and returned to Rome as fresh and strong as a pony. I found the inns very clean and the prices low; and if you can live on soup, delicious trout and char, fowls, veal, puddings and fruit, you will fare famously at an outside average of five francs a day."

As this advice exactly coincided with our own inclinations, we naturally considered it the wisest of all, especially as the invitation to bear-hunts and glacier-scrambles was not particularly tempting to our party. The kind reader will perceive this for himself when he learns that it consisted of an English writer, who, still hale and hearty in spite of his threescore years and ten, regarded botany as the best rural sport; his wife, his faithful companion through many years of sunshine and shadow, who had grown old so naturally that whilst anticipating a joyful Hereafter she still clothed this present life with the poetic hues of her girlhood; their daughter, the present narrator; and their joint friend, another Margaret, who, whilst loyal to her native country, America, had created for herself, through her talent, her[Pg 500] love of true work and her self-dependence, a bright social and artistic life in Italy. As for Perugia, our happy quartette had plenty of opportunities for studying the old masters in the winter months. Now we were anxious to exchange the oppressive, leaden air of the Italian summer for the invigorating breezes of the Alps.

Yet how fresh and graceful Italy still looked as we traveled northward in the second week of June! The affluent and at the same time gentle sunshine streamed through the broad green leaves of the vines, which were flung in elegant festoons from tree to tree. It intensified the bright scarlet of the myriad poppies, which glowed amongst the brilliant green corn. It lighted up the golden water-lilies lying on the surface of the slowly-gliding streams, and brought into still greater contrast the tall amber-colored campanile or the black cypress grove cut in sharp outline against the diaphanous blue sky. We knew, however, that fever could lurk in this very luxury of beauty, while health was awaiting us in the more sombre scenes of gray mountain and green sloping pasture. We traveled on, therefore, by the quickest and easiest route, and alighting from the express-train to Munich at the Brixen station on the Brenner Pass, were shortly deposited, bag and baggage, at that comfortable and thoroughly German inn, the renowned Elephant.

We prided ourselves on being experienced travelers, and consequently immediately secured four places in the Eilwagen, which was to start from the inn at six o'clock the next morning for our destination, Bruneck. We handed over our luggage to the authorities, partook of supper and then retired contentedly to rest—in the case of the two Margarets to the soundest of slumbers—until in the morning we were suddenly awoke, not by the expected knock of the chambermaid, but by a hurrying to and fro of feet, and the sound of several eager voices resounding through the echoing corridors. Fortunately, it was not only perfectly light, but exhausted Nature had enjoyed its allotted spell of sleep; for we found, to our astonishment, that it was past five o'clock. The storm continued outside no whit abated, and in the midst of the human hubbub the father's voice sounded clear and distinct.

"The British lion is roaring," exclaimed Margaret: then, snatching at my attire, I was in the midst of the disturbance in a very few minutes.

My father stood at his door and held in his upraised hand a pair of villainous boots, old and "clouted," fit for the Gibeonites, very different from the substantial English aids to the understanding which he had placed in all good faith outside his door the previous night. A meagre-faced chambermaid was wringing her hands beside him. Two waiters vociferated, whilst a third, whose eyes were still heavy with sleep, was blindly groping at the other doors.

"My excellent London boots, made on a special last, have disappeared," said my father, trying to moderate his indignation, "and this vile rubbish has been substituted in their stead.—Where is your master?" he demanded of the sobbing woman. "Fetch either your master or my boots."

"Herr Je! Herr Je! I've hunted high and low, up stairs and down," murmured the weeping maid, "and the gracious gentleman's boots are nowhere."

"Sir," said a little round-headed man, who seemed to have his wits about him, "I know very well that these are not your boots. I cleaned your grace's boots, and placed them at your door at four o'clock. It is some beggarly Welschers who have crept up stairs and exchanged for them, unawares, their old leather hulks."

"Ah yes," said the wailing woman: "three Welschers, who came for the fair, slept in the barn, and had some bread and cheese before they left, an hour ago."

In the midst of this explanation the door of No. 2 was slightly opened, and an arm in a shirt sleeve appeared and drew in a pair of boots. Hardly, however, was the door closed when the bell of No. 2 began to ring violently.

"Heavens! another pair gone!" exclaimed[Pg 501] a waiter. Then with one accord the whole bevy of distracted servants rushed to No. 2, declaring their innocence.

"My good people, I cannot understand one word you say," replied a mild English voice. "I request you to be gone, and let one of you bring me my own proper boots."

The British lion—who, it must be owned, had reason to roar—became calmed at the evident innocence of the servants and the gentle sounds of this British lamb. He therefore went to the rescue, and explained the matter to No. 2, who in his turn meekly expostulated: "Very vexatious! Dear me! My capital boots made expressly for Alpine climbing! But we must make the best of it, my dear sir."

Maids and men still remained in an excited group, when at this juncture the head-waiter appeared, bringing with him the landlord, a respectable middle-aged man, who, bowing repeatedly, assured the gentlemen of his extreme annoyance at the whole affair, especially as it compromised the fame of his noted house. Indeed, he would gladly refund the loss were the two pairs of boots not forthcoming.

Forthcoming! How could they be forthcoming when at this moment the clock was striking six, and the Eilwagen (Margaret termed it the oil-wagon) was to start at once, and we with it, though minus breakfast? The British lamb departed hurriedly, but we were detained to be told of another complication. Not only were the boots gone, but the royal imperial post-direction of Austria, after duly weighing and measuring our luggage, had adjudged it too heavy and bulky for the roof of its mail-coach. It would, however, restore our money, and even suggest another mode of conveyance, but take us by its Eilwagen it would not.

"The delay is indeed advantageous, mein Herr," said the landlord, addressing my father, who walked about in slippers, "as time will thereby be gained for a thorough investigation of the boot question."

One trouble always modifies another. The disappearance of the boots made us bear the departure of the Eilwagen philosophically. Nay, at the conclusion of a substantial breakfast of hot coffee, ham and eggs we began greatly to enjoy ourselves. Rejected by the post-direction for the Eilwagen, we felt at liberty to choose our time of departure. For the present, therefore, acting as our own masters, we leisurely sauntered out of doors, admired the clean, attractive exterior of the roomy inn, and smiled at the fresco of the huge elephant, which, possessed of gigantic tusks and diminutive tail, carried a man, spear in hand, on his back. A giant bearing a halbert, accompanied by two youths in tunics, completed the group. An inscription informed us that this was the first elephant which had ever visited Teutschland, and that the inn derived its name from the fact of the august quadruped sleeping there on its journey, which took place in the sixteenth century. The worthy landlord had also ordered a fresco to be painted on his inn to the honor of the Virgin. She was depicted standing upon the crescent moon, and her aid was invoked by the good man in rhyme to protect the house "from lightning's rod, O thou Mother of God! From rain and fire, and sickness dire;"—but, alas! there was no mention of thieves.

We were deploring the fact when the worthy Wirth appeared in person, attended by a slim youth in blue-and-silver uniform, whom he introduced to us with considerable emphasis as representing the police. The officer of justice stepped forward and with a low bow took the length and breadth of the Welschers' offending, and promised that the Austrian government would do its best to see the distinguished, very noble Herrschaft righted. We cannot be quite certain that he promised that the emperor would seek the boots in person, but something was said about that mighty potentate. At the assurance of governmental interference how could the British lion fail of being pacified? He declared that the landlord had acted as a gentleman,[Pg 502] shook hands with him, and returning to the house exchanged his slippers for his second pair of boots—very inferior in make and comfort to the missing treasures—and then conferred with the landlord as to the best method for the continuance of our journey.

The Herr Wirth, with whom and the whole household we had now become excellent friends, declared that with our unusual amount of luggage the only plan was a "separat Eilfahrt," which means a separate express-journey to Bruneck. It had, however, its advantages: we should travel quickly and with the greatest ease. As we were willing to accede to his proposition, he handed us over to his clerks in the royal imperial post-bureau, who, having received a round sum of florins, filled in and sanded an important document, which being delivered to us conveyed the satisfactory information that we four individuals, whose ages, personal appearance and social position the head-official had magnanimously passed over with a compassionate flourish, were, on this fourteenth day of June, 1871, to be conveyed to the town of Bruneck in the caleche No. 1990; which said vehicle would be duly furnished with cloth or leather cushions, one foot-carpet, two lamps, main-braces, axletree, etc., including one portion of grease. So far, well and good, but on our inquiring when the said No. 1990 would be ready to start, the head-official merely looked over his spectacles at his subordinate, who in his turn, leaning back in his tall chair and stroking his beard, called out, "Klaus! Klaus!"—a call which was answered by a tall, stolid-looking man, also in livery, who seemed to occupy the post of official hostler.

"Klaus," demanded the second chef, "the Herrschaft ask when the vehicle will be ready."

Klaus gave an astonished stare, and articulated some rapid sounds in a dialect quite unintelligible to us.

"Precisely," returned the subordinate. "The horses are sent for, and when they arrive the Herrschaft will be expedited forthwith."

Whereupon the clerks of the post-direction became suddenly immersed in the duties of their office. We took the hint and good-naturedly retired.

It certainly looked like business when outside we perceived Klaus dragging forth with all his might and main, from a dark and dusty coach-house, a still dustier old coach. Darker it was not, for the color was that of canary, emblazoned with the black double-headed Austrian eagle. This, then, was the caleche No. 1990. It had the air of a veteran officer in the imperial army who had not seen active service for many a long day.

Klaus was too busy to pay much attention to us. He pulled the piece of antiquity into the street, and with an uneasy expression, as if he knew before-hand what he had to expect, he tried and tugged at one of the door-handles. "Sacrament!" he muttered as he at last let go and began hunting in the boot of the coach, under the driver's cushion and in secret nooks and corners, which proved, at the best, mere receptacles for fag-ends of whipcord and cobwebs.

"It is gone, sure enough, the key of the right-hand door." I am afraid it had disappeared three years before, at least, to the fellow's knowledge, for he added in an apologetic but hopeful tone, "It matters not the least, for, see you, all the inns are on the left-hand side."

A glimpse into the coach-house had convinced us of the fact of this vehicle alone being at our disposal; so we determined to manage as best we might, and bore even philosophically the smell of the musty, dust-filled cushions, which Klaus triumphantly pulled out of the open door and beat, as it were, within an inch of their lives.

Briefly, to make two long hours short after several tedious quarters of expectation, a square-set, rosy-faced and middle-aged postilion appeared round the far corner of the village street, resplendent in silver lace and yellow livery, leading three gaunt but sturdy horses. In ten minutes my father was seated on the box and we ladies inside, receiving the good wishes of Klaus, of the landlord,[Pg 503] the men and the maids, now all smiles and curtsies, and with the postilion blowing triumphantly his horn we dashed out of the quaint, dreamy little cathedral town of Brixen.

The road speedily began to ascend, and we looked down from a considerable height on the vast Augustine monastery of Neustift, with its large church, its picturesque cluster of wings, refectories and separate residences of every stage of architecture, lying snugly amongst vineyards, Spanish chestnuts and fig trees. Ever upward, by but above the waters of the rapid Brienz, until at the fortress of Mühlbach we entered the Pusterthal proper.

This old fort commands the valley and spans the road. Our driver, who, according to Austrian regulation, went on foot wherever the ascent was particularly steep, could not enter into our admiration of its romantic position. Hans—for such was his name—could not perceive any grace or beauty in a scene which had often disturbed his imagination and awakened his fear. "Ah," said he, "it is a God-forsaken spot. It is here that many slaughtered Bavarians wander about at night with candles, seeking for their bodies or their souls—I know not which. Look you! My grandmother came from Schliers in Bavaria, and the two countries speak the same language. However, in my father's day, in 1809, Emperor Franz drove the Bavarians and French out of this part of the Tyrol. It was in April, when the Austrian Schatleh came marching through the Pusterthal with his soldiers, and drove the Bavarians before him. Though these were only a handful, they would not make truce, but broke down all the bridges in their retreat. They wanted to burn the bridge at Lorenzen, only the country-folks with blunderbusses, cudgels and pitchforks protected it, and made them run; so they marched on, pursued by the Landsturm, to this fortress, where they fought like devils until many were killed, and the others, at their wits' end, managed to push on to Innsbruck. Yes, glorious days, and long may the Tyrolese cry God, Emperor and Fatherland! But those wandering spirits make my flesh creep. Ugh!"

The road now allowed of the horses being put to a lively trot, interrupting further conversation. We drove steadily on, stopping at comfortable inns in large well-to-do villages, where even the poorest appeared to enjoy in their houses unlimited space. The landlords politely demanded our journey-certificate, solemnly inserted the hour of our arrival and departure, and confirmed the important fact of our remaining exactly the same number of travelers as at the beginning of our journey. We exchange Hans for a youthful Jacobi, and Jacobi for an aged Seppl, who all agreed in their livery if not in their ages; each stage also being at a slightly higher elevation, so that by degrees we had changed the Italian vegetation, which had lingered as far as the neighborhood of Brixen, for the more northern crops of young oats and flax. Yet one prominent reminder of comparatively adjacent Italy accompanied us the greater portion of the three hours' drive. Hundreds of agile, swarthy figures were busily boring, blasting, shoveling and digging for the new railway, which is to convey next season shoals of passengers and civilization, rightly or wrongly so called, into this great yet primitive artery of Southern Tyrol, the Pusterthal already forming, by means of the Ampezzo, a highway between Venice and the Brenner Pass. As the morning advanced the busy sounds of labor ceased, and we saw groups of dark-eyed men reclining in the shade of the rocks, partaking of their frugal dinners of orange-colored polenta—plenten, as our Seppl called it.

So onward by soft slopes bordered by mountain-ridges, all scarped and twisted, having dark green draperies of pine trees cast round their strong limbs, with bees humming in the aromatic yet invigorating breeze fresh from the snow-fields, and swallows wheeling in the clear blue air, until we reached a fertile amphitheatre. A confusion of flourishing villages was scattered over its verdant meadows, and here and there on a jutting rock or mountain-spur a solitary[Pg 504] mediaeval tower or imposing castle stood forth, the most conspicuous of all being a fortress situated on a natural bulwark of rock. Half around its base a little town, which appeared stunted in its growth by the course of the river, confidingly rested. A hill covered with wood screened the other side of the castle, whilst exactly opposite a broad valley ran northward, hemmed in by lofty snow-fields and glaciers that sparkled in the noonday sun. Natural hummocks or knolls covered with wood broke the uniformity of this upland plain, which still ascended eastward to the higher, bleaker Upper Pusterthal. This valley continues to mount to yet more sterile regions, until, reaching the great watershed of the Toblacher Plain, which sends part of its streams to the Adriatic, the others to the more distant Black Sea, it gradually dips down again to the fruitful wine-regions of Lienz.

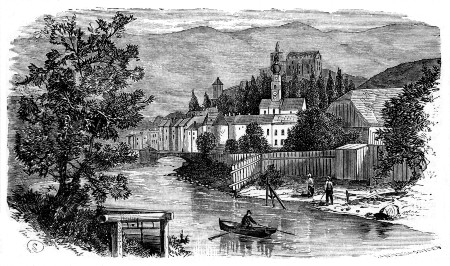

BRUNECK.

BRUNECK.

We have now, however, to do with Bruneck, where our venerable 1990 had safely deposited us at the modern inn, the Post. We might almost style it the fashionable inn, for it was kept by a gentleman of noble birth and the representative of the province, who, having a large family of growing children, had wisely let his gentility take care of itself and permitted his guests to be entertained at their own rather than at his expense. As the noble landlady was suffering from headache, the dapper waitress took charge of us, provided us with rooms, and then installed us at the early table-d'hôte, where a number of the officers of the garrison, with some other regular diners, whom we learnt to recognize in time as the town bailiff, the apothecary and the advocate, were despatching, in the midst of great clatter and bustle, the inevitable kalbsfleisch and mehlspeis.

The lady who had recommended us to go to the Pusterthal had likewise assured us that the Post at Bruneck would satisfy all our requirements. In this she was mistaken. It is true that tastes differ, especially amongst tourists, who may be divided into two classes—those who merely care for the country, let them disguise it as they will, when they can endue it with the features of their town-life; and those who love the country for the sake of Nature, and thus endeavor to carry trails of freshness back with them to town. Now, it was all artificial dust and din that we desired to get rid of. We had traveled in search of verdant meadows, brawling streams and sweet-scented woods. We could not find solace and relaxation in sitting at the windows of our respectable inn to watch every passer-by on the dusty boulevard below, in spending half the day indoors, let it be ever so comfortably, or in merely turning out in the evening to shop in the puny town, whilst we bemoaned the want of a circulating library and a brass band. It was even more intolerable, as the Post had been built perversely with its back to the fine view of the glaciers. Moreover, the whole establishment was in the hands of bricklayers, painters and glaziers, who were enlarging and repairing it for the comfort and convenience of future but certainly not of present visitors.

As trade was evidently flourishing, we had not the slightest hesitation in ringing for Maria, the kellnerin, and consulting with her about the mode of our procuring country lodgings as soon as possible. Maria was a good-natured girl and willing to serve us, but our ideas could not be so easily carried out as we had anticipated. One of us had the folly to suggest vacant rooms being to let in the castle.

"Gracious!" replied Maria, casting her eyes up to the sky. "In the castle! Why, that's crown property, and filled with the military. Really, I don't know how I can help you, since the gentlemen officers have engaged for themselves every apartment inside or outside the town."

We spoke of the many neighboring villages, which were filled with grand old houses.

Maria declared they were better outside than inside, and that the Bauers who dwelt in them could scarcely find bedding for their cattle, much less for Christian gentlefolks. "There is the Herr Apotheker's house at Unterhofen, but he will not let that. There is the Hof at Adelsheim: it's out of the question. There is also Frau Sieger's in the same village, but that is let to the Herr Major for the season. Look you! you had better go to Frau Sieger. Stay, I will send Lina with you."

Lina proved to be one of the blossoms of the noble family tree. She led my[Pg 505] mother and me to Frau Sieger, but what came of our afternoon's expedition deserves to be told in a fresh chapter.

Now, this house-hunting was a piece of business to be got through as soon as possible. Nevertheless, three hours elapsed before we returned to the hotel. We found the father and Margaret leaning their heads out of a corridor window, and when we asked them what they were about, she replied, "We have been wishing that the grand old mansion in yonder village were only a pension, where we could obtain rooms. But have you met with any success?"

"A pension! That sounds like Meran or Switzerland, instead of this primitive Pusterthal. Only let us have tea, and we will tell you what we have done."

"Very good! We will be patient; but you do not look dissatisfied with your afternoon," said my father.

Nor in truth were we. Sipping our mild tea, we related our adventures. The little girl Lina had taken us into the town, which consisted of one narrow street in the shape of a half-moon, where houses of all ages and ranks squeezed against each other and peeped into each other's windows with the greatest familiarity. In one of the largest of these Frau Sieger lived. Her husband was the royal imperial tobacco agent, and the house was crammed full of chests of the noxious and obnoxious weed, the passages and landing being pervaded with a sweet, sickly smell of decomposing tobacco. In the parlor, however, where Frau Sieger sat drinking coffee with her lady friends, the aromatic odor of the beverage acted as a disinfectant. The hostess drew us aside, listened complacently to our message, and then graciously volunteered to let us rooms under her very roof.

We should have chosen chemical works in preference! There was, then, nothing to be done but to take leave with thanks. Accompanied by the little Lina, we passed under the town-gate,[Pg 506] and whilst sorely perplexed perceived a pleasant village, at the distance of about a mile, lying on the hillside in a wealth of orchards and great barns. The way thither led across fields of waving green corn, the point where the path diverged from the high-road being marked by a quaint mediaeval shrine, one of the many shrines which, sown broadcast over the Tyrol, are intended to act as heavenly milestones to earth-weary pilgrims.

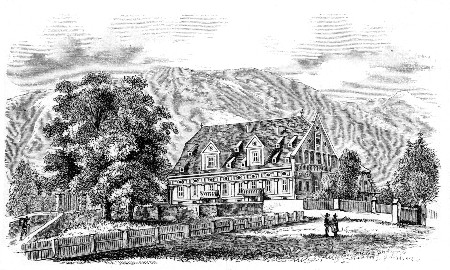

ADELSHEIM—OUR HOME IN THE TYROL.

ADELSHEIM—OUR HOME IN THE TYROL.

That was the village of Adelsheim, Lina said, where their own country-house was situated, and Freieck, belonging to Frau Sieger; and there, at the farther extremity of the village, was Schönburg, where old Baron Flinkenhorn lived. The biggest house of all on the hill was the Hof, and that below, with the gables and turrets, the carpenter's.

The bare possibility of finding a resting-place in that little Arcadia made us determine to go thither. We would try the inn, and then the carpenter's.

The inn proved a little beer-shop, perfectly impracticable. A woman with a bright scarlet kerchief bound round her head, who was washing outside the carpenter's, told us in Italian that she and her husband, an overseer on the new railway, occupied with their family every vacant room, which was further confirmed by the carpenter popping his head out of an upper window, and in answer to Lina's question giving utterance to an emphatic "Na, na, I hab koan" ("No, no, I have none").

Lina was so sure that the Hofbauer would not let rooms, for he was a wealthy man and owned land for miles around, that she stayed at a respectful distance whilst we approached nearer to at least admire the grand old mansion, even if it were closed against us as a residence. The village was full of marvelous old houses rich in frescoes, oriel windows, gables and turrets, but this dwelling, standing in a dignified situation on an eminence, was a prince amongst its compeers. The architecture, which was Renaissance, might belong to a bad style, but the long slopes of roof, the jutting balconies, the rich iron-work on the oblong façade, the painted sun-dial and the coats-of-arms now fading away into oblivion, the grotesque gargoyle which in the form of a dragon's head frowned upon the world,—each detail, that had once been carefully studied, helped to form a complete whole which it was a pleasure to look upon. The grand entrance, no longer used, was guarded by a group of magnificent trees, the kings of the region. Traces of an old pleasure-garden[Pg 507] and the dried-up basin of a fountain were visible within.

At this point in the narrative Margaret exclaimed, "None other than my would-be pension! I have known it from the first, so pray do not keep me on tenterhooks. Were you or were you not successful? Yet all hope has died within me already, for such a treasure-trove we never could get."

"Well, listen," said the mother. "As we were admiring the house, a handsome, fair-haired young man, one's perfect ideal of a peasant, came along the road, bowed to us, and when we expressed our interest in the mansion said that he was the son of the house, and that we might see the rooms if we liked. Grand old rooms they are, with a great lack of furniture, but nevertheless perfectly charming. The young man, who is named Anton, thought his father would probably have no objection to let us rooms. At all events, we could all go over and see the Hofbauer at ten o'clock to-morrow morning, when he would be in: he was in his fields this afternoon. The whole, in fact, was a pastoral poem."

The next day we were as punctual as clock-work. A pleasant, comely young peasant woman, who looked as if she had lived on fresh air all her life, met us in the great stone entrance-hall. She told us that her father would soon be at liberty, and that, with our permission, she would again show us the rooms if we wished to see them. This promised well. Fetching a huge bunch of handsome iron-wrought keys, she conducted us into the great hall of the first floor, hung with large unframed pictures of the Holy Sacrament. Then unlocking a handsome door which had once been green and gold, we entered the vast reception-room, almost bereft of furniture, but possessing a pine floor of milky whiteness and a remarkably fine stove of faience eight feet high. My father measured the length of the apartment: it was forty feet, and could have seated a hundred guests. The casements were filled with old lozenge-shaped glass set in lead, and the fine old iron trellis-work on the outside of the windows gave a wonderfully mediaeval look to the apartment. There was, moreover, a magnificent bay window, which formed a little room of itself, besides a second room much less, which, with carved wood wainscot and ceiling, could have served as an oratory.

Margaret's delight was unbounded. The father smiled quietly, and we the pioneers could scarcely refrain our pride and pleasure. But there was more to be seen. Crossing the great hall once more, we entered a large and beautiful room overlooking the main entrance. This had other furniture besides its handsome porcelain stove and inlaid floor of dark wood. There was not only a comfortable modern bed, but chairs, sofa and table; a chest of drawers too, which was covered with innumerable religious knickknacks—little sacred pictures in glass frames, miniature saints, and artificial flowers in small china pots. Having dipped her finger in a holy-water shell hanging on the wall, our guide drew back a long chintz curtain which covered the end of the room, and showed us a large and handsome chapel below. A fald-stool ran along the front of the window which, with an additional lattice of gilt and carved wood, separated the room from the church. This had evidently been in old times the apartment of the lord and his lady, and here they had knelt and listened to the holy office without mingling with their dependants below. This room, if we had the good fortune to obtain lodgings in the mansion, was to belong to the poetess, for it was full of inspiration and old-world memories.

Then out again into the hall and up another flight of stone stairs, through a second great lobby into a corridor, which communicated on either side with two charming rooms, spotlessly clean and perfectly empty, if I except the stoves; but still, if we chose, these two rooms could be Margaret's and mine, and the corridor as well, with a beautiful balcony which commanded an enchanting view of the rich Pusterthal up and down, right and left, with a row of jagged, contorted dolomite mountains thrown into[Pg 508] the bargain. All this was to be ours if only the Hofbauer would have us. So down we went, casting longing looks around us—down into the entrance-hall, where a crowd of poor people were streaming out of the stube, the parlor of the family, such as in the midland counties of England would be called the house-place, and so into the grassy court in front, where we awaited with anxious hearts the fiat of the Hofbauer.

We were not long kept waiting. In another minute the master of the house stood before us, a tall, thin, elderly man, dressed in the full costume of the district—an embroidered cloth jacket, black leather breeches, which displayed a broad band of naked knee, green ribbed stockings, shoes and buckles, with a silver cord and tassel on his broad beaver hat. Saluting us with the grace and ease of a courtier, he apologized for keeping us waiting, but he had been entertaining the poor of the parish at dinner, according to an old custom of his. These simple Tyrolese dined, then, at ten o'clock in the morning!

An elderly woman, also tall and spare, now appeared in a bright blue linen apron, that half hid her thickly-plaited black woolen petticoat, which was short enough to give full effect to scarlet knit stockings and low, boat-shaped shoes. She carried in her hand a plate of large hot fat cakes, which she pressed upon us; then pitied the smallness of our appetites, and urged two apiece at least. Two mouthfuls, however, were sufficient, as the cakes were not only extremely greasy, but filled with white curds, aniseed and chives. Having received in good part this intended hospitality, we were rejoiced to hear the Hofbauer express his perfect willingness that we should take up our abode at the mansion. We need merely pay him a trifle, but we must furnish ourselves the extra bedsteads. Moidel, his daughter, could cook for us, for she understood making dishes for bettermost people, having been sent by him to Brixen for a year to learn cooking; for what was a moidel (maiden) good for that could not cook? He should not make any charge for her services. Also, if we saw any bits of furniture about the house that suited us we might take them; and lastly, we could stay until Jacobi, the 25th of July, but on that day the best bedroom must be given up, as it belonged to his son, the student, who would return from Innsbruck about that day. All this was charming. We promised to procure beds and bedding in Bruneck, and arranged to take possession of our new quarters on the following morning.

I will not enter into the rashness of our promise respecting the bedsteads, merely hinting at the difficulties and complications which beset us. Some of these can be imagined when it is known that, firstly, there proved not to be an upholsterer, nor even a seller of old furniture, at Bruneck; and that, secondly, the officers and soldiers of the garrison now quartered there occupied by night every available spare bed in the township. So it seemed until in our embarrassment the landlady of the Post arose from her bed to help us to procure some. The interview ended again with the prudent advice, "Go to Frau Sieger." We went, and that incomparable lady, who bore us no malice for refusing her rooms, generously provided for a small sum three bedsteads and an amazing, and what appeared to us superfluous, amount of bolsters, pillows, feather beds, winter counterpanes; but she would hear no nay, declaring, "It often turned very chilly in the Pusterthal, and at such times a warm bed was a godsend."

We now began to dream of beds of roses, but we were mistaken: we were crying before we were out of the wood. We arrived at the Hof the following afternoon with our bag and baggage, and found Moidel, otherwise Maria, busily preparing the newly-erected bed in the state-room. She received us cordially, until my mother, laying her shawl on the bedstead belonging to the house, remarked that she wished that for herself.

Maria seemed suddenly thunderstruck. She turned a deep red, and with a gesture of astonishment let drop a pillow, exclaiming, "Heavens alive! that is the Herr Student's bed!"[Pg 509]

She fled from the chamber, bringing back her aunt to the rescue. The latter looked stern and aggrieved. "Never, never! no one must lay his head on that pillow but the student," she cried. Had my mother asked to repose on the altar of the chapel they could not have been more dumbfoundered.

As Frau Sieger's beds were truly spare, and as she could merely provide three, this second complication ended in the family giving up a bed of their own—one which was adorned at the head and foot with a cross, a bleeding heart and sacred monogram—one, in fact, which bore more marks of sanctity about it than the sacred bed of the student. It was obvious that this mysterious individual was consecrated to the Church, and that even before his ordination all that he touched was holy.

The storm had again given place to sunshine, and the two quiet women passed gently to and fro with coarse but sweet-scented linen, which they fetched from an old chest adorned with red tulips, a crown of thorns and the legend "K. M., 1820," on a bright blue ground. Good old Kaetana! That chest had once been crammed full to overflowing with linen which, like other young women, she had spun for her own dowry, but when the Hofbauerin died Kathi became the housekeeper and mother to the little children. Thus the contents of the chest had gradually decreased, until the maiden aunt drew forth the four last pair of new sheets for these passing strangers. She felt it no sacrifice. It would have grieved her more to touch the piles of fine new linen which she and Moidel had spun through many a long winter evening, and which were now safely hidden away in the great mahogany wardrobe, which the Hofbauer, in harmony with the more luxurious ideas of the age, had given to his daughter. It occupied the place of honor in the great saloon, having three companion chests of drawers of lesser dimensions, which the father at the same time had presented to each of his sons. That of the eldest, Anton, was emptied by the owner and placed by him at our disposal; that of the second, the student, was carefully guarded from the sun by a covering formed of newspapers; the third, belonging to Jacobi, the youngest, appeared to us filled with books. Jacob was shy, and some days elapsed before we became acquainted. Anton, however, appeared modestly ready to attend to our least beck and call. The first evening, perceiving that we had no candlesticks, we conferred with Anton.

"Freilich," he said. "We have none of our own, but I am sure that, as you will take care of them, there can be no great harm in lending you some of the Virgin's." We demurred at first, but with a smile on his open, ingenuous face he added, "The Herrschaft may be quite sure that I would not sin against my conscience." He then brought half a dozen plated candlesticks from the little sacristy, which he committed to our care.

The reader must not suppose that this was a disused chapel: far from it. In the dusk of the summer evening a murmuring chant like the musical hum of bees pervaded the vast old mansion, which was otherwise hushed in perfect silence. It was the Rosenkranz (or rosary) repeated by the household in the chapel. The Hofbauer knelt on one side near the altar, and led the service, his two sons, the four men-servants, the aunt and Moidel, with the three maid-servants, reciting the responses on their respective sides. The even-song over, the household quietly retired to rest.

Chance had graciously brought us to the Hof in the midst of preparations for the festival of the Holy Father. On Sunday, June 18, the whole Catholic world was to celebrate the astounding fact of Pio Nono having exceeded the days of Saint Peter. We, who had come from Rome, where thirty upstart papers were denouncing time-honored usages and formulas, where many of the people had begun to sneer at the Papacy and to take gloomy views of the Church, were not prepared for the religious fervor and devotion to the Papal See which greeted us in the Tyrol, especially at Bruneck, where from time immemorial a race of[Pg 510] the staunchest adherents to Rome had flourished. The mere fact that we came from the Eternal City clothed us with brilliant but false colors. Endless were the questions put to us about the health and looks of the Holy Father, whom they believed to be kept in a dungeon and fed on bread and water—a diet, however, turned into heavenly food by the angels. Perhaps the most perplexing question of all was, whether the Herr Baron Flinkenhorn, who had been born in exactly the same year as the Holy Father, bore the faintest resemblance to that saintly martyr. We could but shake our heads as the old nobleman was pointed out to us on the morning of the festival. Decrepit and bent with age, he shuffled along by the side of his old tottering sister, an antiquated couple dressed in the French fashions of 1810. They hardly perceived, so blind and old were they, the bows and greetings which they received. They knew, however, that it was Pio's festival, and they made great offerings to the Church and to the poor.

Deafness even has its compensations. Thus this old couple had not been kept awake all night by the ringing of bells and the firing of small cannon, which had continued incessantly since the setting of the sun had ushered in the festival on the previous evening. The firing lasted all day—a popular but very startling and disturbing mode of expressing joy and satisfaction. Bruneck wreathed and flagged its houses: there were processions, the prettiest being considered that of the female pupils of the convent of the Sacred Heart, who walked in white, bearing lilies. At night the good Sisters made a grand display of sacred transparencies in their convent windows—rhymes about the age of Saint Peter and the Pope; the Virgin rescuing the sinking vessel of the Church; Saint Peter seated on his emblematic rock, with his present successor at his side; and so forth—all wondered, gaped at and admired by the people, until the great spectacle of the evening commenced. As soon as night had fairly set in a hundred fires blazed upon the mountains—far as the eye could reach, for miles and many miles, one dazzling gigantic illumination. Papal monograms, crosses, tiaras shone forth in startling proportions. High up, far from any human habitation, on the verge of the snow, in clearings of the mountain forests, on Alpine pastures, these fiery letters had been patiently traced by toiling men and lads. Anton and Jacobi were not behind-hand, and by means of two hundred little bonfires had devised the papal initials on the upland common behind the house. The illumination, however, had not begun to reach its full splendor when one quick flash of lightning succeeded another, followed by a rolling artillery of thunder, the precursors of heavy down-pouring rain. In five minutes the storm had extinguished every bright emblem, and plunged the illuminated mountains into impenetrable blackness. The weather, grimly triumphant, drove lads and lasses drenched to their homes. So ended the festival, but in the morning, in dry clothes, every one had the pleasure of imagining how beautiful the spectacle would have been but for the rain.

Margaret Howitt.

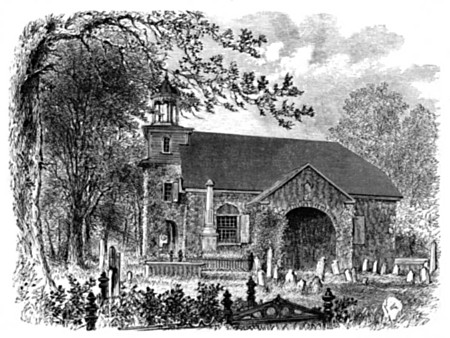

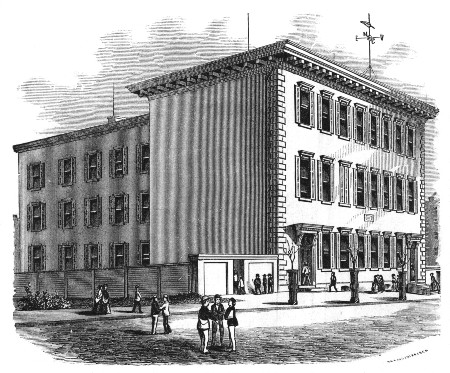

OLD SWEDES' CHURCH.

OLD SWEDES' CHURCH.

We have pointed out the metropolis of Delaware as being a distinctly Northern city, planted in the distinct South. Among other things, this complication has led to some singularities in its settlement. As a community regulated by the most liberal traditions of Penn, but placed under the legal conditions of a slave State, it has held a position perfectly anomalous. No other spot could be indicated where the contrasts of North and South came to so sharp an edge; and there are few where a skilled pen could set down so many curiosities of folk-lore and confusions of race. The Dutch, the Swedes and the English Quakers formed the substratum, upon which were poured the émigrés of the French Revolution and the fugitives from Santo Domingo. The latter sometimes brought slaves who had continued faithful, and who retained their serfdom under the laws of Delaware. The French bonnes stood on washing-benches in the Brandywine, and taught the amazed Quaker wives that laundry-work could be done in cold water. The names of grand old French families, prefaced by the proprietarial forms of le and du, became mixed by marriage with such Swedish names as Svensson and such Dutch names as Staelkappe. (The first Staelkappe was a ship's cook, nicknamed from his oily and glossy bonnet.) As for the refugees from Santo Domingo, they absolutely invaded Wilmington, so that the price of butter and eggs was just doubled in 1791, and house-rents rose in proportion. They found themselves with rapture where the hills were rosy with peach-blossoms, and where every summer was simply an extract from Paradise.

We cannot linger, as we fain would[Pg 512] do, over the quaint and amusing Paris en Amerique which reigned here for a period following the events of '93. At Sixth and French streets lived a marchioness in a cot, which she adorned with the manners of Versailles, the temper of the Faubourg St. Germain and the pride of Lucifer. This Marquise de Sourci was maintained by her son, who made pretty boxes of gourds, and afterward boats, in one of which he was subsequently wrecked on the Delaware, before the young marquis was of age to claim his title. In a farm-house, whose rooms he lined with painted canvas, lived Colonel de Tousard. On Long Hook Farm resided, in honor and comfort, Major Pierre Jaquette, son of a Huguenot refugee who married a Swedish girl, and became a Methodist after one of Whitefield's orations: as for the son, he served in thirty-two pitched battles during our Revolution. Good Joseph Isambrie, the blacksmith, used to tell in provincial French the story of his service with Bonaparte in Egypt, while his wife blew the forge-bellows. Le Docteur Bayard, a rich physician, cured his compatriots for nothing, and Doctor Capelle, one of Louis XVI.'s army-surgeons, set their poor homesick old bones for them when necessary. Monsieur Bergerac, afterward professor in St. Mary's College, Baltimore, was a teacher: another preceptor, M. Michel Martel, an émigré of 1780, was proficient in fifteen languages, five of which he had imparted to the lovely and talented Theodosia Burr. Aaron Burr happened to visit Wilmington when the man who had trained his daughter's intellect was lying in the almshouse, wrecked and paralytic, with the memory of all his many tongues gone, except the French. Some benevolent Wilmingtonians approached Burr in his behalf, showing the colonel's own letter which had introduced him to the town.

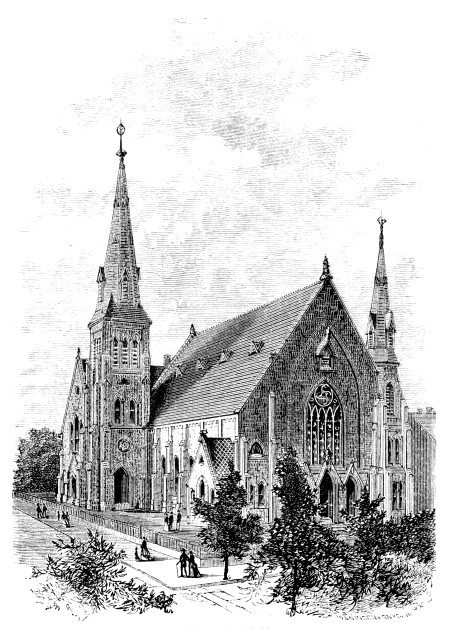

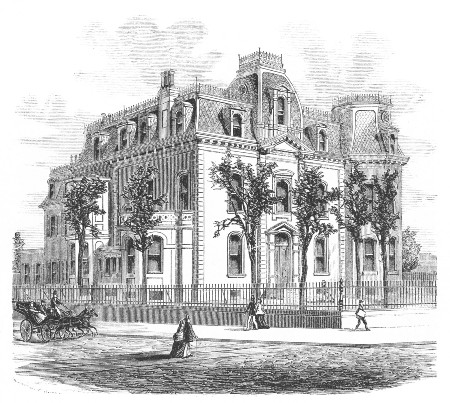

GRACE CHURCH.

GRACE CHURCH.

"I wrote that letter when I knew him," said the diplomatic Colonel Burr, "but I know him no more."

The day quickly came when Burr's speech of denial was reflected upon himself, and those who then honored him "knew him no more."

Another French teacher, by the by, was not of Gallic race, but that of Albion le perfide: this was none other than William Cobbett, with his reputation all before him, known only to the Wilmington millers for the French lessons he[Pg 513] gave their daughters and the French grammar he had published. He lived on "Quaker Hill" from 1794 to 1796. He then went to Philadelphia, and began to publish Peter Porcupine's Gazette. "I mean to shoot my quills," said Cobbett, "wherever I can catch game." With the sinews of Wilmington money he soon made his way back to England, became a philosopher, and sat in the House of Commons. Another British exile was Archibald Hamilton Rowan, an Irish patriot, and one of the "United Irishmen" of 1797. Escaping from a Dublin jail in woman's clothes, he found his way to Wilmington after adventures like those of Boucicault's heroes; lived here several years in garrets and cottages, carrying fascination and laughter wherever he went among his staid neighbors; and after some years flew back to Ireland, glorious as a phoenix, resuming the habits proper to his income of thirty thousand pounds a year.

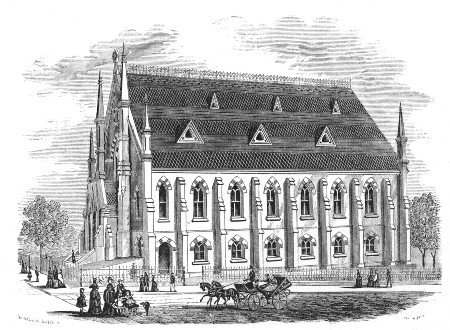

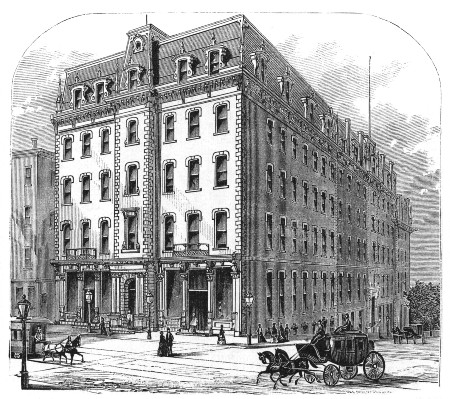

WEST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH.

WEST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH.

A familiar figure on the wharves of Wilmington was the gigantic one of Captain Paul Cuffee, looking like a character in a masquerade. His athletic limbs forced into the narrow garments of the Quakers, and a brim of superior development shading his dark negro face, he talked sea-lingo among the trading captains, mixed with phrases from Robert Barclay and gutturals picked up on the coast of Sierra Leone. Captain Cuffee owned several vessels, manned by sailors as black as shoemaker's wax, and he conducted one of his ships habitually to the African ports. Coming back rich from Africa, this figure of darkness has often led its crew of shadows into port at the Brandywine mouth, passing modestly amongst the whalers and wheat-shallops, dim as the Flying Dutchman and mum as Friends' meeting. It is possible that from some visit of his arose the legend that Blackbeard, the terrible pirate, who always hid his booty on the margins of streams, had used the Brandywine for this purpose. At any rate, some clairvoyants, in their dreams, saw in 1812 the glittering pots of Blackbeard's gold lying beneath the rocks of Harvey's waste-land, next to Vincent Gilpin's mill. They paid forty thousand dollars for a small tract, and searched[Pg 514] and found nothing; but Job Harvey hugged his purchase money.

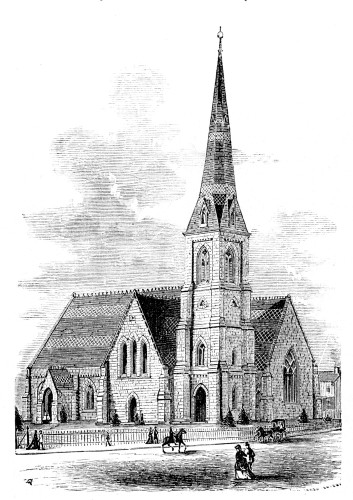

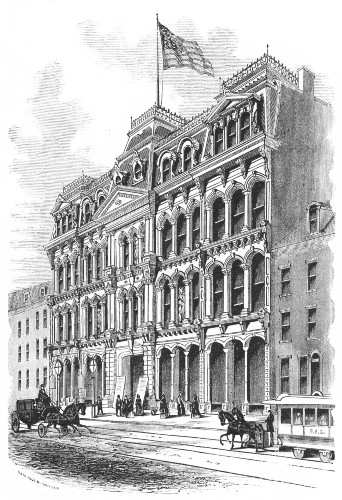

ST. JOHN'S PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCH.

ST. JOHN'S PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCH.

Latrobe the architect lived here in the first quarter of the century, midway between Philadelphia (where he was building waterworks and banks) and Washington (where he was seating a young nation in legislative halls worthy of its greatness); using Wilmington meanwhile as a pleasant retirement, where he could wear his thinking-cap, educate his beautiful young daughter, and mix with the French and other cultured society of the place. Here, too, about fifty years ago, a pretty French girl used to play and eat peaches, maintained by funds mysteriously supplied from Louisiana, and ignorant of all connections except a peculating guardian. It was little Myra Clark (now Mrs. Gaines), who woke up one day to find herself the heroine of the greatest of modern lawsuits, and the credited possessor of a large part of New Orleans—the same who has recently gained a million, while she expects to gain a million more, and to be richer than Lady Burdett-Coutts.

Thus has the pretty city ever played its part as a storing-house where things and people and ideas might be set by to ripen. It is not wonderful that it now and then found itself, quite unintentionally, a museum, where the far-brought rarities were living souls. In a heavenly climate, just where the winged songsters of the South held tryst with those of the North, and where the plants of both latitudes embowered the gardens together, Nature arranged a new garden wherein were brought together almost all the races that had diverged from Babel.

The antiquities we have been examining, however, yield in age to the venerable walls which were built to shelter a worship no longer promulgated among us. The Swedes' churches of Philadelphia and Wilmington are among the oldest civilized fabrics to be found in this new country of ours. That of Wilmington was built in 1698, and that at Wicaco in Philadelphia in 1700. Rudman, a missionary from Sweden, preached the first sermon to the Wilmingtonians in May, 1699; and after him a succession of Swedish apostles arrived, trembling at their own courage, and feeling as our preachers would do if assigned to posts in Nova Zembla or Patagonia. The salary offered was a hundred rixdollars, with house and glebe, and the creed was the Lutheran doctrines according to "the Augsburg Confession of Faith, free from all human superstition and tradition." Dutch ministers alternated peaceably with the Swedish ones, who bore such Latinized names as Torkillus, Lokenius, Fabricius, Hesselius, Acrelius. The last wrote in his own language an excellent history of the Swedish settlements on the Delaware, only a part of which has been rendered into English by the New York Historical Society. William Penn proved his tolerance by giving the little church a folio Bible and[Pg 515] a shelf of pious books, together with a bill of fifty pounds sterling. The building was planted half a mile away from the then city, in the village of Christinaham. Its site was on the banks of the Christine, and its congregation, in the comparative absence of roads, came in boats or sleighs, according to the season. The church was well built of hard gray stone, with fir pews and a cedar roof: iron letters fixed in the walls spelled out such holy mottoes as "Lux L. I. Tenebr. oriens ex Alto," and "Si de. pro Nobis Quis contra Nos," and commemorated side by side the names of William III., king of England, William Penn, proprietary, and Charles XI. of Sweden. Swedish services were continued up to about the epoch of the Revolution, when, the language being no longer intelligible in the colony, they were merged into English ones: the last Swedish commissary, Girelius, returned by order of the archbishop in 1786, and the intercourse between the American Swedish churches and the ecclesiastical see in the fatherland ceased for ever. The oldest headstone in the churchyard is that of William Vandevere, who died in 1719. Service was long celebrated by means of the chalice and plate sent over by the Swedish copper-miners to Biorch, the first missionary at Cranehook, and the Bible given[Pg 516] by Queen Anne in 1712. The sexes sat separately. In our grandfathers' day the old sanctuary used to be dressed for Christmas by the sexton, Peter Davis: he was a Hessian deserter, with a powder-marked face and murderous habits toward the English language. Descending from their sledges and jumpers, the congregation would crowd toward the bed of coals raked out in the middle of the brick floor from the old cannon stove: to do this they must brush by the cedars which "Old Powderproof" had covered with flour, in imitation of snow; and then Dutch Peter, as they complimented him on his efforts, would whisper the astonishing invocation, "God be tankful for all dish plessins and tings!"

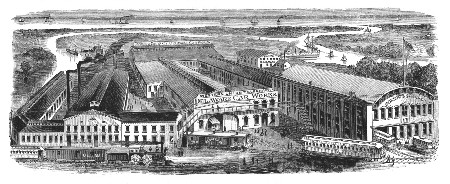

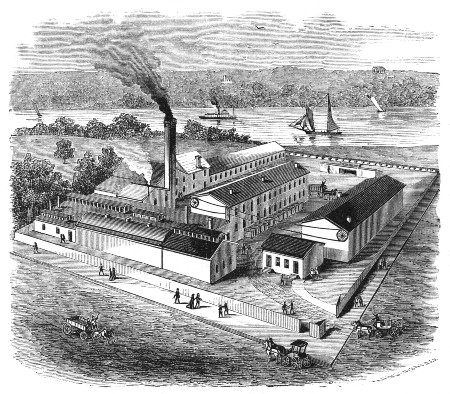

CAR-BUILDING WORKS.

CAR-BUILDING WORKS.

Modern improvement has a particular spite against the landmarks of antiquity. The railroad to Baltimore slices off a part of the Swedish graveyard—an institution much more ancient than the church which stands on it. And the rock by old Fort Christina, upon which Governor Stuyvesant—Irving's Stuyvesant—stood on his silver leg and took the surrender of the Swedish governor-general, is now quarried out and reconstructed into Delaware Breakwater.

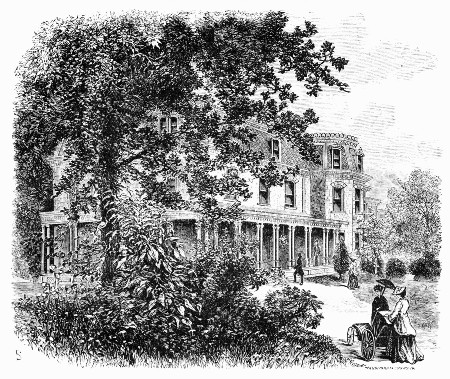

RESIDENCE OF JOB JACKSON, ESQ.

RESIDENCE OF JOB JACKSON, ESQ.

Doubtless we dwell too fondly on the old memories, but it appears that the souvenirs of this region are somewhat remarkable for their contrast of nationalities. Perhaps the colonization of other spots would yield better romances than any we have to offer; yet we cannot help feeling that a better pen than ours would find brilliant matter for literary effects in the paradise revealed to good Elizabeth Shipley by her dream-guide.

Delawarean Wilmington is perhaps hardly known to the general public except through two of its products. Everybody buys Wilmington matches, and everybody knows that Du Pont's powder is made in the vicinity. Ignoring the foundries and shipyards, the popular imagination recognizes but these two commodities—the powder which could[Pg 517] blow up the obstructions to all the American harbors, and the match which could touch off the train. A million dollars' worth of gunpowder and three hundred thousand dollars' worth of matches are the annual product.

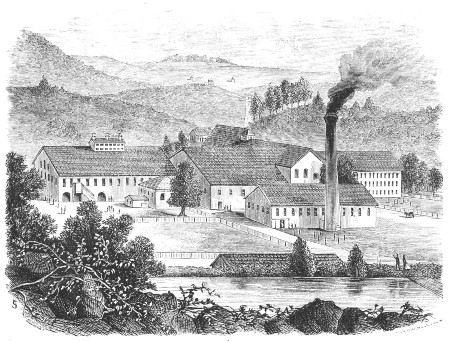

CAR-WHEEL CASTING WORKS.

CAR-WHEEL CASTING WORKS.

Eleuthère Irenée Du Pont, a French gentleman of honorable family, appeared in Wilmington in 1802. The town had at that time hardly three thousand inhabitants. He amazed all the quidnuncs by buying, for fifty thousand dollars, Rumford Dawes' old tract of rocks on the Brandywine, which everybody knew was perfectly useless. The stranger was pitied as he began to blast away the stone. Out of a single rock, separated into fragments, he built a cottage: it was a lonely spot, and the snakes from the fissures were in the habit of sharing the contents of his well-bucket. Such was the beginning of the Eleuthère Powder-works. M. Du Pont, who died some forty years ago, was much beloved for his benevolence and probity. In 1825, La Fayette, during his celebrated visit of reminiscence, was the guest of the brave old Frenchman for several days, during which he examined the battle-ground of Brandywine. He here received the ball with which he got his wound in that battle, from the hands of Bell McClosky, a kind of camp-follower and nurse, who had extracted the bullet with her[Pg 518] scissors and preserved it. The general wrote in the album of Mademoiselle Du Pont the following graceful sentiment:

"After having seen, nearly half a century ago, the bank of the Brandywine a scene of bloody fighting, I am happy now to find it the seat of industry, beauty and mutual friendship.

While on a Revolutionary topic we may mention that among a great many relics of '76 preserved in the town is the sword of General Wayne—"Mad Anthony"—a straight, light blade in leather scabbard, possessed by Mr. W. H. Naff.

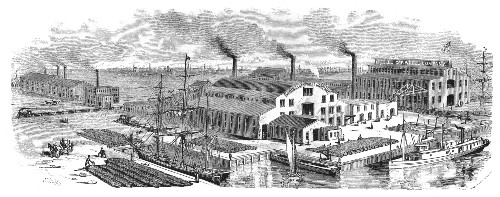

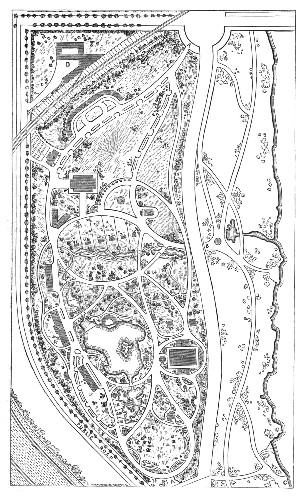

JESSUP & MOORE'S PAPER-MILLS.

JESSUP & MOORE'S PAPER-MILLS.

The citizens of this pleasant town have ever been orderly and pious, just as they have ever been loyal. Their religious institutions have grown and flourished. Godfearing and unspeculative, they have attached themselves to such creeds as appealed most powerfully to the heart with the least possible admixture of form. "The words Fear God" says Joubert, "have made many men pious: proofs of the existence of God have made many men atheists." Since the day when Whitefield poured out his eloquence among the Brandywine valleys and touched the hearts of the French exiles, Methodism, with its almost entire absence of dogma, has had great success in the community. This success is now indicated by a rich congregation, and a church-building that would be called noble in any city. Grace Church, on Ninth and West streets, is a large Gothic temple, seating nearly eight hundred persons—warmed, frescoed and heavily carpeted inside, and walled externally with brownstone mixed with the delicate pea-green serpentine of Chadd's Ford. The architect was a native Wilmingtonian—Thomas Dixon—now of Baltimore. The windows, including a very brilliant oriel, are finely stained: the font is a delicate piece of carving, the organ is grand, and the accommodations for Sunday-schools and lectures are of singular perfection. Few shrines in this country show better the modern movement of Methodism toward luxury and elegance, as compared with the repellant humiliations of Wesley's day.[Pg 519]

It is to be hoped that this advance in attractiveness does not indicate any lapse in the more solid qualities of spiritual earnestness. "Whenever this altar," well said Bishop Simpson in dedicating the building on the centenary anniversary of the rise of Methodism—"whenever this altar shall be too fine for the poorest penitent sinner to kneel here, the Spirit of God will depart, and that of Ichabod will come in."

We have indicated the Swedish Lutheran missionaries exhorting under the roof of their antique church in a language which their congregations were beginning to forget, and afterward in a broken English hardly more intelligible. Their place is largely taken now by predicators of the faith of John Knox, with a plentiful following of pious believers. Among the family of Presbyterian kirks in Wilmington the youngest is a large brick edifice built in 1871, for sixty-one thousand dollars, on Eighth and Washington streets, able to seat nearly a thousand persons, most comfortably and invitingly furnished, and supplied with lecture-, infant- and Sunday-school-rooms, together with a huge kitchen, suggesting the agapæ or love-feasts of the primitive Christians. Meantime, Anglicanism does not lack supporters. The descendants of Monsieur Du Pont, cultured and influential, have done much to advance the creed, and about fifteen years ago Mr. Alexis I. Du Pont, pulling down a low tavern in the suburbs, prepared to erect a church upon the site, to be built mainly through his own liberality. Unhappily, Mr. Du Pont died from the effects of an explosion at the powder-works ten weeks after the laying of the corner-stone; but the building was soon completed through the pious munificence of his widow, and the Bible of St. John's Protestant Episcopal Church now rests on its lectern upon the site of the old liquor-bar, and the gambling-den of former days is replaced by its pews. The rector is Mr. T. Gardiner Littell, a man of eminent goodness and intelligence. St. John's has a beautiful open roof, stained windows and a fine organ: it can offer seats to seven hundred worshipers.

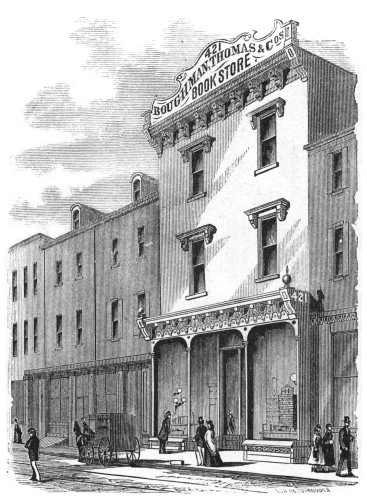

"AT THE SIGN OF SHAKESPEARE."

"AT THE SIGN OF SHAKESPEARE."

These few specimen churches—and especially the last, which blots out a grogshop—are good instances, with the large congregations they accommodate, of the way in which a sane, flourishing manufacturing community provides for the spiritual needs of its members. The tone and moral well-being which Boz found, or thought he found, among the operatives at Lowell are largely realized here. But our picture of Wilmington as a hive of industry is not yet complete, and before we enter upon the highly-interesting[Pg 520] problem of its dealings with its working family, we should enter a few more of its sample manufactories.

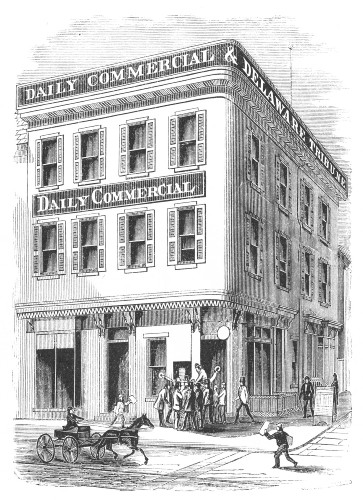

OFFICE OF THE DAILY COMMERCIAL.

OFFICE OF THE DAILY COMMERCIAL.