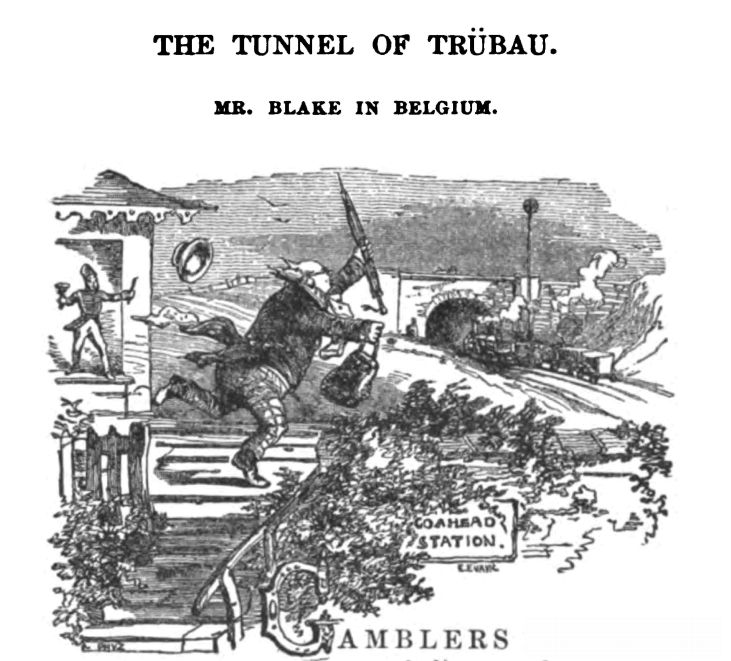

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Tales Of The Trains, by Charles James Lever

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Tales Of The Trains

Being Some Chapters of Railroad Romance by Tilbury Tramp,

Queen's Messenger

Author: Charles James Lever

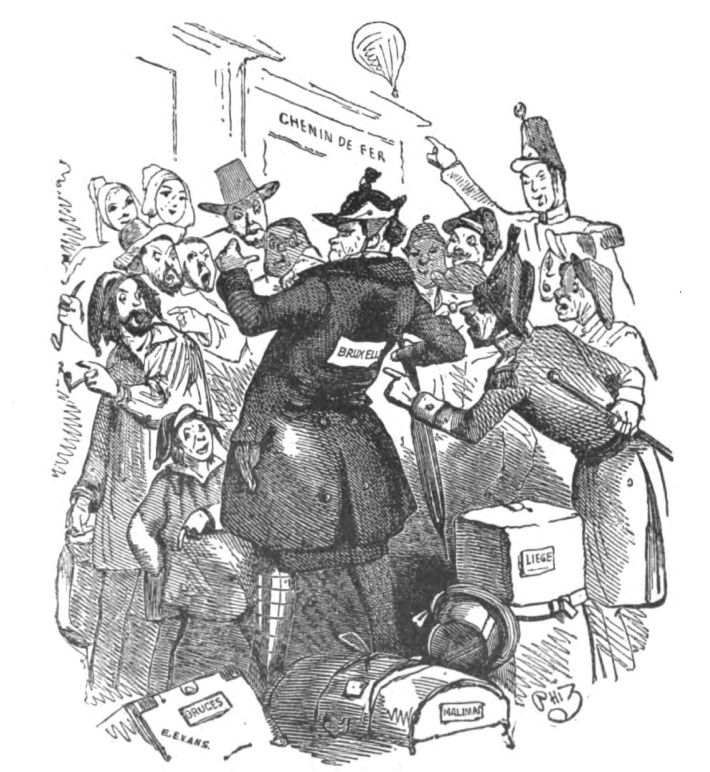

Illustrator: Phiz.

Release Date: January 8, 2011 [EBook #34884]

Last Updated: November 6, 2012

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TALES OF THE TRAINS ***

Produced by David Widger

Bang, bang, bang!

Shake, shiver, and throb;

The sound of our feet Is the piston's beat,

And the opening valve our sob!

|

THE COUPÉ OF THE NORTH MIDLAND |

Let no enthusiast of the pastoral or romantic school, no fair reader with eyes "deeply, darkly, beautifully blue," sneer at the title of my paper. I have written it after much and mature meditation.

It would be absurd to deny that the great and material changes which our progress in civilization and the arts effect, should not impress literature as well as manners; that the tone of our thoughts, as much as the temper of our actions, should not sympathize with the giant strides of inventive genius. We have but to look abroad, and confess the fact. The facilities of travel which our day confers, have given a new and a different impulse to the human mind; the man is no longer deemed a wonder who has journeyed some hundred miles from home,—the miracle will soon be he who has not been everywhere.

To persist, therefore, in dwelling on the same features, the same fortunes, and the same characters of mankind, while all around us is undergoing a great and a formidable revolution, appears to me as insane an effort as though we should try to preserve our equilibrium during the shock of an earthquake.

The stage lost much of its fascination when, by the diffusion of literature, men could read at home what once they were obliged to go abroad to see. Historical novels, in the same way, failed to produce the same excitement, as the readers became more conversant with the passages of history which suggested them. The battle-and-murder school, the raw-head-and-bloody-bones literature, pales before the commonest coroner's inquest in the "Times;" and even Boz can scarce stand competition with the vie intime of a union workhouse. What, then, is to be done? Quæ regio terræ remains to be explored? Have we not ransacked every clime and country,—from the Russian to the Red Man, from the domestic habits of Sweden to the wild life of the Prairies? Have we not had kings and kaisers, popes, cardinals, and ministers, to satiety? The land service and the sea service have furnished their quota of scenes; and I am not sure but that the revenue and coast-guard may have been pressed into the service. Personalities have been a stock in trade to some, and coarse satires on well-known characters of fashionable life have made the reputation of others.

From the palace to the poorhouse, from the forum to the factory, all has been searched and ransacked for a new view of life or a new picture of manners. Some have even gone into the recesses of the earth, and investigated the arcana of a coal-mine, in the hope of eliciting a novelty. Yet, all this time, the great reformer has been left to accomplish his operations without note or comment; and while thundering along the earth or ploughing the sea with giant speed and giant power, men have not endeavored to track his influence upon humanity, nor work out any evidences of those strange changes he is effecting over the whole surface of society. The steam-engine is not merely a power to turn the wheels of mechanism,—it beats and throbs within the heart of a nation, and is felt in every fibre and recognized in every sinew of civilized man.

How vain to tell us now of the lover's bark skimming the midnight sea, or speak of a felucca and its pirate crew stealing stealthily across the waters! A suitor would come to seek his mistress in the Iron Duke, of three hundred horse-power; and a smuggler would have no chance, if he had not a smoking-galley, with Watt's patent boilers!

What absurdity to speak of a runaway couple, in vain pursued by an angry parent, on the road to Gretna Green! An express engine, with a stoker and a driver, would make the deserted father overtake them in no time!

Instead of the characters of a story remaining stupidly in one place, the novelist now can conduct his tale to the tune of thirty miles an hour, and start his company in the first class of the Great Western. No difficulty to preserve the unities! Here he journeys with bag and baggage, and can bring twenty or more families along with him, if he like. Not limiting the description of scenery to one place or spot, he whisks his reader through a dozen counties in a chapter, and gives him a bird's-eye glance of half England as he goes; thus, how original the breaks which would arise from an occasional halt, what an afflicting interruption to a love story, the cry of the guard, "Coventry, Coventry, Coventry;" or, "Any gentleman, Tring, Tring, Tring;" with the more agreeable interjection of "Tea or coffee, sir?—one brandy and soda-water—'Times,' 'Chronicle,' or 'Globe.'"

How would the great realities of life flash upon the reader's mind, and how insensibly would he amalgamate fact with fiction! And, lastly, think, reflect, what new catastrophe would open upon an author's vision; for while, to the gentler novelist, like Mrs. Gore, an eternal separation might ensue from starting with the wrong train, the bloody-minded school would revel in explosions and concussions, rent boilers, insane luggage-trains, flattening the old gentlemen like buffers. Here is a vista for imagination, here is scope for at least fifty years to come. I do not wish to allude to the accessory consequences of this new literary school, though I am certain music and the fine arts would both benefit by its introduction; and one of the popular melodies of the day would be "We met; 't was in a tunnel." I hope my literary brethren will appreciate the candor and generosity with which I point out to them this new and unclaimed spot in Parnassus. No petty jealousies, no miserable self-interests, have weighed with me. I am willing to give them a share in my discovered country, well aware that there is space and settlement for us all,—locations for every fancy, allotments for every quality of genius. For myself I reserve nothing; satisfied with the fame of a Columbus, I can look forward to a glorious future, and endure all the neglect and indifference of present ingratitude. Meanwhile, less with the hope of amusing the reader than illustrating my theory, I shall jot down some of my own experiences, and give them a short series of the "Romance of a Railroad."

But, ere I begin, let me make one explanation for the benefit of the reader and myself.

The class of literature which I am now about to introduce to the public, unhappily debars me from the employment of the habitual tone and the ordinary aids to interest prescriptive right has conferred on the novelist. I can neither commence with "It was late in the winter of 1754, as three travellers," etc., etc.; or, "The sun was setting" or, "The moon was rising;" or, "The stars were twinkling;" or, "On the 15th Feb., 1573, a figure, attired in the costume of northern Italy, was seen to blow his nose;" or, in fact, is there a single limit to the mode in which I may please to open my tale. My way lies in a country where there are no roads, and there is no one to cry out, "Keep your own side of the way." Now, then, for—

"The English are a lord-loving people, there's no doubt of it," was the reflection I could not help making to myself, on hearing the commentaries pronounced by my fellow-travellers in the North Midland, on a passenger who had just taken his departure from amongst us. He was a middle-aged man, of very prepossessing appearance, with a slow, distinct, and somewhat emphatic mode of speaking. He had joined freely and affably in the conversation of the party, contributing his share in the observations made upon the several topics discussed, and always expressing himself suitably and to the purpose; and although these are gifts I am by no means ungrateful enough to hold cheaply, yet neither was I prepared to hear such an universal burst of panegyric as followed his exit.

"The most agreeable man, so affable, so unaffected." "Always listened to with such respect in the Upper House."

"Splendid place, Treddleton,—eighteen hundred acres, they say, in the demesne,—such a deer-park too." "And what a collection of Vandykes!" "The Duke has a very high opinion of his—"

"Income,—cannot be much under two hundred thousand, I should say."

Such and such-like were the fragmentary comments upon one who, divested of so many claims upon the respect and gratitude of his country, had merely been pronounced a very well-bred and somewhat agreeable gentleman. To have refused sympathy with a feeling so general would have been to argue myself a member of the anti-corn law league, the repeal association, or some similarly minded institution; so that I joined in the grand chorus around, and manifested the happiness I experienced in common with the rest, that a lord had travelled in our company, and neither asked us to sit on the boiler nor on the top of the luggage, but actually spoke to us and interchanged sentiments, as though we were even intended by Providence for such communion. One little round-faced man with a smooth cheek, devoid of beard, a. pair of twinkling gray eyes, and a light brown wig, did not, however, contribute his suffrage to the measure thus triumphantly carried, but sat with a very peculiar kind of simper on his mouth, and with his head turned towards the window, as though to avoid observation. He, I say, said nothing, but there was that in the expression of his features that said, "I differ from you," as palpably as though he had spoken it out in words.

The theme once started was not soon dismissed; each seemed to vie with his neighbor in his knowledge of the habits and opinions of the titled orders, and a number of pleasant little pointless stories were told of the nobility, which, if I could only remember and retail here, would show the amiable feeling they entertain for the happiness of all the world, and how glad they are when every one has enough to eat, and there is no "leader" in the "Times" about the distress in the manufacturing districts. The round-faced man eyed the speakers in turn, but never uttered a word; and it was plain that he was falling very low in the barometer of public opinion, from his incapacity to contribute a single noble anecdote, even though the hero should be only a Lord Mayor, when suddenly he said,—

"There was rather a queer sort of thing happened to me the last time I went the Nottingham circuit."

"Oh, do you belong to that circuit?" said a thin-faced old man in spectacles. "Do you know Fitzroy Kelly?"

"Is he in the hardware line? There was a chap of that name travelled for Tingle and Crash; but he's done up, I think. He forged a bill of exchange in Manchester, and is travelling now in another line of business."

"I mean the eminent lawyer, sir,—I know nothing of bagmen."

"They're bagmen too," replied the other, with a little chuckling laugh, "and pretty samples of honesty they hawk about with them, as I hear; but no offence, gentlemen,—I'm a CG. myself."

"A what?" said three or four together.

"A commercial gentleman, in the tape, bobbin, and twist line, for Rundle, Trundle, and Winningspin's house, one of the oldest in the trade."

Here was a tumble down with a vengeance,—from the noble Earl of Heaven knows what and where, Knight of the Garter, Grand Cross of the Bath, Knight of St. Patrick, to a mere C. G.,—a commercial gentleman, travelling in the tape, bobbin, and twist line for the firm of Rundle, Trundle, and Winningspin, of Leeds. The operation of steam condensing, by letting in a stream of cold water, was the only simile I can find for the sudden revulsion; and as many plethoric sobs, shrugs, and grunts issued from the party as though they represented an engine under like circumstances. All the aristocratic associations were put to flight at once; it seemed profane to remember the Peerage in such company; and a general silence ensued, each turning from time to time an angry look towards the little bagman, whose mal-à-propos speech had routed their illustrious allusions.

Somewhat tired of the stiff and uncomfortable calm that succeeded, I ventured in a very meek and insinuating tone to remind the little man of the reminiscence he had already begun, when interrupted by the unlucky question as to his circuit.

"Oh! it ain't much of a story," said he. "I should n't wonder if the same kind of thing happens often,—mayhap, too, the gentlemen would not like to hear it, though they might, after all, for there's a Duke in it."

There was that in the easy simplicity with which he said these words, vouching for his good temper, which propitiated at once the feelings of the others; and after a few half-expressed apologies for having already interrupted him, they begged he would kindly relate the incident to which he alluded.

"It is about four years since," said he. "I was then in the printed-calico way for a house in Nottingham; business was not very good, my commission nothing to boast of—cotton looking down—nothing lively but quilted woollens, so that I generally travelled in the third class train. It wasn't pleasant, to be sure; the company, at the best of times, a pretty considerable sprinkling of runaway recruits, prisoners going to the assizes, and wounded people run over by the last train; but it was cheap, and that suited me. Well, one morning I took my ticket as usual, and was about to take my place, when I found every carriage was full; there was not room for my little portmanteau in one of them; and so I wandered up and down while the bell was ringing, shoving my ticket into every one's face, and swearing I would bring the case before Parliament, if they did not put on a special train for my own accommodation, when a smart-looking chap called out to one of the porters,—

"'Put that noisy little devil in the coupé; there's room for him there.'

"And so they whipped my legs from under me, and chucked me in, banged the door, and said, 'Go on;' and just as if the whole thing was waiting for a commercial traveller to make it all right, away went the train at twenty miles an hour. When I had time to look around, I perceived that I had a fellow-traveller, rather tall and gentlemanly, with a sallow face and dark whiskers; he wore a brown upper-coat, all covered with velvet,—the collar, the breasts, and even the cuffs,—and I perceived that he had a pair of fur shoes over his boots,—signs of one who liked to make himself comfortable. He was reading the 'Morning Chronicle,' and did not desist as I entered, so that I had abundant time to study every little peculiarity of his personal appearance, unnoticed by him.

"It was plain, from a number of little circumstances, that he belonged to that class in life who have, so to say, the sunny side of existence. The handsome rings which sparkled on his fingers, the massive gold snuff-box which he coolly dropped into the pocket of the carriage, the splendid repeater by which he checked the speed of the train, as though to intimate you had better not be behind time with me, made me heave an involuntary sigh over that strange but universal law of Providence by which the goods of fortune are so unequally distributed. For about two hours we journeyed thus, when at last my companion, who had opened in succession some half-dozen newspapers, and, after skimming them slightly, thrown them at his feet, turned to me, and said,—

"'Would you like to see the morning papers, sir?' pointing as he spoke, with a kind of easy indifference, to the pile before him. 'There's the "Chronicle," "Times," "Globe," "Sun," and "Examiner;" take your choice, sir.'

"And with that he yawned, stretched himself, and, letting down the glass, looked out; thereby turning his back on me, and not paying the slightest attention to the grateful thanks by which I accepted his offer.

"'Devilish haughty,' thought I; 'should n't wonder if he was one of the great mill-owners here,—great swells they are, I hear.'

"'Ah! you read the "Times," I perceive,' said he, turning round, and fixing a steadfast and piercing look on me; 'you read the "Times,"—a rascally paper, an infamous paper, sir, a dishonest paper. Their opposition to the new poor law is a mere trick, and their support of the Peel party a contemptible change of principles.'

"Lord! how I wished I had taken up the 'Chronicle'! I would have paid a week's subscription to have been able to smuggle the 'Examiner' into my hand at that moment.

"'I 'm a Whig, sir,' said he; 'and neither ashamed nor afraid to make the avowal,—a Whig of the old Charles Fox school,—a Whig who understands how to combine the happiness of the people with the privileges of the aristocracy.'

"And as he spoke he knitted his brows, and frowned at me, as though I were Jack Cade bent upon pulling down the Church, and annihilating the monarchy of these realms.

"'You may think differently,' continued he,—'I perceive you do: never mind, have the manliness to avow your opinions. You may speak freely to one who is never in the habit of concealing his own; indeed, I flatter myself that they are pretty well known by this time.'

"'Who can he be?' thought I. 'Lord John is a little man, Lord Melbourne is a fat one; can it be Lord Nor-manby, or is it Lord Howick?' And so I went on to myself, repeating the whole Whig Peerage, and then, coming down to the Lower House, I went over every name I could think of, down to the lowest round of the ladder, never stopping till I came to the member for Sudbury.

"'It ain't him,' thought I; 'he has a lisp, and never could have such a fine coat as that.'

"'Have you considered, sir,' said he, 'where your Toryism will lead you to? Have you reflected that you of the middle class—I presume you belong to that order?'

"I bowed, and muttered something about printed cottons.

"'Have you considered that by unjustly denying the rights of the lower orders under the impression that you are preserving the prerogative of the throne, that you are really undermining our order?'

"'God forgive us,' ejaculated I. 'I hope we are not.'

"'But you are,' said he; 'it is you, and others like you, who will not see the anomalous social condition of our country. You make no concessions until wrung from you; you yield nothing except extorted by force; the finances of the country are in a ruinous condition,—trade stagnated.'

"'Quite true,' said I; 'Wriggles and Briggs stopped payment on Tuesday; there won't be one and fourpence in the pound.'

"'D—n Wriggles and Briggs!' said he; 'don't talk to me of such contemptible cotton-spinner—'

"'They were in the hardware line,—plated dish-covers, japans, and bronze fenders.'

"'Confound their fenders!' cried he again; 'it is not of such grubbing fabricators of frying-pans and fire-irons I speak; it is of the trade of this mighty nation,—our exports, our imports, our colonial trade, our foreign trade, our trade with the East, our trade with the West, our trade with the Hindoos, our trade with the Esquimaux.'

"'He's Secretary for the Colonies; he has the whole thing at his finger-ends.'

"'Yes, sir,' said he, with another frown, 'our trade with the Esquimaux.'

"'Bears are pretty brisk, too,' said I; 'but foxes is falling,—there will be no stir in squirrels till near spring. I heard it myself from Snaggs, who is in that line.'

"'D—n Snaggs,' said he, scowling at me.

"'Well, d—n him,' said I, too; 'he owes me thirteen and fonrpence, balance of a little account between us.'

"This unlucky speech of mine seemed to have totally disgusted my aristocratic companion, for he drew his cap down over his eyes, folded his arms upon his breast, stretched out his legs, and soon fell asleep; not, however, with such due regard to the privileges of the humbler classes as became One of his benevolent Whig principles, for he fell over against me, flattening me into a corner of the vehicle, where he used me as a bolster, and this for thirty-two miles of the journey.

"'Where are we?' said he, starting up suddenly; 'what's the name of this place?'

"'This is Stretton,' said I. 'I must look sharp, for I get out at Chesterfield.'

"'Are you known here,' said my companion, 'to any one in these parts?'

"'No,' said I, 'it is my first turn on this road.'

"He seemed to reflect for some moments, and then said, 'You pass the night at Chesterfield, don't you?' and, without waiting for my answer, added, 'Well, we 'll take a bit of dinner there. You can order it,—six sharp. Take care they have fish,—it would be as well that you tasted the sherry; and, mark me! not a word about me;' and with that he placed his finger on his lips, as though to impress me with inviolable secrecy. 'Do you mind, not a word.'

"'I shall be most happy,' said I, 'to have the pleasure of your company; but there's no risk of my mentioning your name, as I have not the honor to know it.'

"'My name is Cavendish,' said he, with a very peculiar smile and a toss of his head, as though to imply that I was something of an ignoramus not to be aware of it.

"'Mine is Baggs,' said I, thinking it only fair to exchange.

"'With all my heart, Raggs,' said he, 'we dine together,—that's agreed. You 'll see that everything's right, for I don't wish to be recognized down here;' and at these words, uttered rather in the tone of a command, my companion opened a pocket-book, and commenced making certain memoranda with his pencil, totally unmindful of me and of my concurrence in his arrangements.

"'Chesterfield, Chesterfield, Chesterfield,—any gentleman for Chesterfield?' shouted the porters, opening and shutting doors, as they cried, with a rapidity well suited to their utterance.

"'We get out here,' said I; and my companion at the same moment descended from the carriage, and, with an air of very aristocratic indifference, ordered his luggage to be placed in a cab. It was just at this instant that my eye caught the envelope of one of the newspapers which had fallen at my feet, and, delighted at this opportunity of discovering something more of my companion, I took it up and read—what do you think I read?—true as I sit here, gentlemen, the words were, 'His Grace the Duke of Devonshire, Devonshire House.' Lord bless me, if all Nottingham, had taken the benefit of the act I could n't be more of a heap,—a cold shivering came over me at the bare thought of anything I might have said to so illustrious a personage. 'No wonder he should d—n Snaggs,' thought I. 'Snaggs is a low, sneaking scoundrel, not fit to clean his Grace's shoes.'

"'Hallo, Raggs, are you ready?' cried the Duke.

"'Yes, your Grace—my Lord—yes, sir,' said I, not knowing how to conceal my knowledge of his real station. I would have given five shillings to be let sit outside with the driver, rather than crush myself into the little cab, and squeeze the Duke up in the corner.

"'We must have no politics, friend Raggs,' said he, as we drove along,—'you and I can't agree, that's plain.'

"'Heaven forbid, your Grace; that is, sir,' said I, 'that I should have any opinions displeasing to you. My views—'

"'Are necessarily narrow-minded and miserable. I know it, Raggs. I can conceive how creatures in your kind of life follow the track of opinion, just as they do the track of the road, neither daring to think or reflect for themselves. It is a sad and a humiliating picture of human nature, and I have often grieved at it.' Here his Grace blew his nose, and seemed really affected at the degraded condition of commercial travellers.

"I must not dwell longer on the conversation between us,—if that, indeed, be called conversation where the Duke spoke and I listened; for, from the moment the dinner appeared,—and a very nice little clinner it was: soup, fish, two roasts, sweets, and a piece of cheese,—his Grace ate as if he had not a French cook at home, and the best cellar in England.

"'What do you drink, Raggs?' said he; 'Burgundy is my favorite, though Brodie says it won't do for me; at least when I have much to do in "the House." Strange thing, very strange thing I am going to mention to you,—no Cavendish can drink Chambertin,—it is something hereditary. Chambers mentioned to me one day that very few of the English nobility are without some little idiosyncrasy of that kind. The Churchills never can taste gin; the St. Maurs faint if they see strawberries and cream.'

"'The Baggs,' said I, 'never could eat tripe.' I hope he did n't say 'D—n the Baggs;' but I almost fear he did.

"The Duke ordered up the landlord, and, after getting the whole state of the cellar made known, desired three bottles of claret to be sent up, and despatched a messenger through the town to search for olives. 'We are very backward, Raggs,' said he. 'In England we have no idea of life, nor shall we, as long as these confounded Tories remain in power. With free trade, sir, we should have the productions of France and Italy upon our tables, without the ruinous expenditure they at present cost.'

"'You don't much care for that,' said I, venturing a half-hint at his condition.

"'No,' said he, frankly; 'I confess I do not. But I am not selfish, and would extend my good wishes to others. How do you like that Lafitte? A little tart,—a Very little. It drinks cold,—don't you think so?'

"'It is a freezing mixture,' said I. 'If I dare to ask for a warm with—'

"'Take what you like, Raggs—only don't ask me to be of the party;' and with that he gazed at the wine between himself and the candle with the glance of a true connoisseur.

"'I'll tell you,' said he, 'a little occurrence which happened me some years since, not far from this; in fact, I may confess to you, it was at Chatsworth. George the Forth came down on a visit to us for a few days in the shooting-season,—not that he cared for sport, but it was an excuse for something to do. Well, the evening he arrived, he dined in his own apartment, nobody with him but—'

"Just at this instant the landlord entered, with a most obsequious face and an air of great secrecy.

"'I beg pardon, gentlemen,' said he; 'but there's a carriage come over from Chats worth, and the footman won't give the name of the gentleman he wants.'

"'Quite right,—quite right,' said the Duke, waving his hand. 'Let the carriage wait. Come, Raggs, you seem to have nothing before you.'

"'Bless your Grace,' said I, 'I 'm at the end of my third tumbler.'

"'Never mind,—mix another;' and with that he pushed the decanter of brandy towards me, and filled his own glass to the brim.

"'Your health, Raggs,—I rather like you. I confess,' continued he, 'I've had rather a prejudice against your order. There is something d——d low in cutting about the country with patterns in a bag.'

"'We don't,' said I, rather nettled; 'we carry a pocket-book like this.' And here I produced my specimen order; but with one shy of his foot the Duke sent it flying to the ceiling, as he exclaimed,—

"'Confound your patchwork!—try to be a gentleman for once!'

"'So I will, then,' said I. 'Here's your health, Devonshire.'

"'Take care,—take care,' said he, solemnly. 'Don't dare to take any liberties with me,—they won't do;' and the words made my blood freeze.

"I tossed off a glass neat to gain courage; for my head swam round, and I thought I saw his Grace sitting before me, in his dress as Knight of the Garter, with a coronet on his head, his 'George' round his neck, and he was frowning at me most awfully.

"'I did n't mean it,' said I, pitifully. 'I am only a bagman, but very well known on the western road,—could get security for three hundred pounds, any day, in soft goods.'

"'I am not angry, old Raggs,' said the Duke. 'None of my family ever bear malice. Let us have a toast,—"A speedy return to our rightful position on the Treasury benches."'

"I pledged his Grace with every enthusiasm; and when I laid my glass on the table, he wrung my hand warmly and said,—

"'Raggs, I must do something for you.'

"From that moment I felt my fortune was made. The friendship—and was I wrong in giving it that title?—the friendship of such a man was success assured; and as I sipped my liquor, I ran over in my mind the various little posts and offices I would accept of or decline. They 'll be offering me some chief-justiceship in Gambia, or to be port-surveyor in the Isle of Dogs, or something of that kind; but I won't take it, nor will I go out as bishop, nor commander of the forces, nor collector of customs to any newly discovered island in the Pacific Ocean. 'I must have something at home here; I never could bear a sea-voyage,' said I, aloud, concluding my meditation by this reflection.

"'Why, you are half-seas-over already, Raggs,' said the Duke, as he sat puffing his cigar in all the luxury of a Pacha. 'I say,' continued he, 'do you ever play a hand at écarté, or vingt-et-un, or any other game for two?'

"'I can do a little at five-and-ten,' said I, timidly; for it is rather a vulgar game, and I did n't half fancy confessing it was my favorite.

"'Five-and-ten!' said the Duke; 'that is a game exploded even from the housekeeper's room. I doubt if they'd play it in the kitchen of a respectable family. Can you do nothing else?'

"Pope-joan and pitch-and-toss were then the extent of my accomplishments; but I was actually afraid to own to them; and so I shook my head in token of dissent.

"'Well, be it so,' said he, with a sigh. 'Touch that bell, and let us see if they have a pack of cards in the house.'

"The cards were soon brought, a little table with a green baize covering—it might have been a hearth-rug for coarseness—placed at the fire, and down we sat. We played till the day was beginning to break, chatting and sipping between time; and although the stakes were only sixpences, the Duke won eight pounds odd shillings, and I had to give him an order on a house in Leeds for the amount. I cared little for the loss, it is true. The money was well invested,—somewhat more profitably than the 'three-and-a-halfs,' any way.

"'Those horses,' said the Duke,—'those horses will feel a bit cold or so by this time. So I think, Raggs, I must take my leave of you. We shall meet again, I 've no doubt, some of these days. I believe you know where to find me in town?'

"'I should think so,' said I, with a look that conveyed more than mere words. 'It is not such a difficult matter.'

"'Well, then, good-bye, old fellow,' said he, with as warm a shake of the hand as ever I felt in my life. 'Goodbye. I have told you to make use of me, and, I repeat it, I 'll be as good as my word. We are not in just now; but there 's no knowing what may turn up. Besides, whether in office or out, we are never without our influence.'

"What extent of professions my gratitude led me into, I cannot clearly remember now; but I have a half-recollection of pledging his Grace in something very strong, and getting a fit of coughing in an attempt to cheer, amid which he drove off as fast as the horses could travel, waving me a last adieu from the carriage window.

"As I jogged along the road on the following day, one only passage of the preceding night kept continually recurring to my mind. Whether it was that his Grace spoke the words with a peculiar emphasis, or that this last blow on the drum had erased all memory of previous sounds; but so it was,—I continued to repeat as I went, 'Whether in office or out, we have always our influence.'

"This sentence became my guiding star wherever I went. It supported me in every casualty and under every misfortune. Wet through with rain, late for a coach, soaked in a damp bed, half starved by a bad dinner, overcharged in an inn, upset on the road, without hope, without an 'order,' I had only to fall back upon my talisman, and rarely had to mutter it twice, ere visions of official wealth and power floated before me, and imagination conjured up gorgeous dreams of bliss, bright enough to dispel the darkest gloom of evil fortune; and as poets dream of fairy forms skipping from the bells of flowers by moonlight, and light-footed elves disporting in the deep cells of water-lilies or sailing along some glittering stream, the boat a plantain-leaf, so did I revel in imaginary festivals, surrounded by peers and marquises, and thought I was hobnobbing with 'the Duke,' or dancing a cotillon with Lord Brougham at Windsor.

"I began to doubt if a highly imaginative temperament, a richly endowed fancy, a mind glowing with bright and glittering conceptions, an organization strongly poetical, be gifts suited to the career and habits of a commercial traveller. The base and grovelling tastes of manufacturing districts, the low tone of country shopkeepers, the mean and narrow-minded habits of people in the hardware line, distress and irritate a man with tastes and aspirations above smoke-jacks and saucepans. He may, it is true, sometimes undervalue them; they never, by any chance, can understand him. Thus was it from the hour I made the Duke's acquaintance,—business went ill with me; the very philosophy that supported me under all my trial seemed only to offend them; and more than once I was insulted, because I said at parting, 'Never mind,—in office or out, we have always our influence.' The end of it was, I lost my situation; my employers coolly said that my brain did n't seem all right, and they sent me about my business,—a pleasant phrase that,—for when a man is turned adrift upon the world, without an object or an occupation, with nowhere to go to, nothing to do, and, mayhap, nothing to eat, he is then said to be sent about his business. Can it mean that his only business then is to drown himself? Such were not my thoughts, assuredly. I made my late master a low bow, and, muttering my old refrain 'In office or out,' etc., took my leave and walked off. For a day or two I hunted the coffee-houses to read all the newspapers, and discover, if I could, what government situations were then vacant; for I knew that the great secret in these matters is always to ask for some definite post or employment, because the refusal, if you meet it, suggests the impression of disappointment, and, although they won't make you a Treasury Lord, there 's no saying but they may appoint you a Tide-waiter. I fell upon evil days,—excepting a Consul for Timbuctoo, and a Lord Lieutenant for Ireland, there was nothing wanting,—the latter actually, as the 'Times' said, was going a-begging. In the corner of the paper, however, almost hidden from view, I discovered that a collector of customs—I forget where exactly—had been eaten by a crocodile, and his post was in the gift of the Colonial Office. 'Come, here's the very thing for me,' thought I. '" In office or out"—now for it;' and with that I hurried to my lodgings to dress for my interview with his Grace of Devonshire.

"There is a strange flutter of expectancy, doubt, and pleasure in the preparation one makes to visit a person whose exalted sphere and higher rank have made him a patron to you. It is like the sensation felt on entering a large shop with your book of patterns, anxious and fearful whether you may leave without an order. Such in great part were my feelings as I drove along towards Devonshire House; and although pretty certain of the cordial reception that awaited me, I did not exactly like the notion of descending to ask a favor.

"Every stroke of the great knocker was answered by a throb at my own side, if not as loud, at least as moving, for my summons was left unanswered for full ten minutes. Then, when I was meditating on the propriety of a second appeal, the door was opened and a very sleepy-looking footman asked me, rather gruffly, what I wanted.

"'To see his Grace; he is at home, is n't he?'

"'Yes, he is at home, but you cannot see him at this hour; he's at breakfast.'

"'No matter,' said I, with the easy confidence our former friendship inspired; 'just step up and say Mr. Baggs, of the Northern Circuit,—Baggs, do you mind?'

"'I should like to see myself give such a message,' replied the fellow, with an insolent drawl; 'leave your name here, and come back for your answer.'

"'Take this, scullion,' said I, haughtily, drawing forth my card, which I did n't fancy producing at first, because it set forth as how I was commercial traveller in the long hose and flannel way, for a house in Glasgow. 'Say he is the gentleman his Grace dined with at Chesterfield in March last.'

"The mention of a dinner struck the fellow with such amazement that without venturing another word, or even a glance at my card, he mounted the stairs to apprise the Duke of my presence.

"'This way, sir; his Grace will see you,' said he, in a very modified tone, as he returned in a few minutes after.

"I threw on him a look of scowling contempt at the alter-ation his manner had undergone, and followed him upstairs. After passing through several splendid apartments, he opened one side of a folding-door, and calling out 'Mr. Baggs,' shut it behind me, leaving me in the presence of a very distinguished-looking personage, seated at breakfast beside the fire.

"'I believe you are the person that has the Blenheim spaniels,' said his Grace, scarce turning his head towards me as he spoke.

"'No, my Lord, no,—never had a dog in my life; but are you—are you the Duke of Devonshire?' cried I, in a very faltering voice.

"'I believe so, sir,' said he, standing up and gazing at me with a look of bewildered astonishment I can never forget.

"'Dear me,' said I, 'how your Grace is altered! You were as large again last April, when we travelled down to Nottingham. Them light French wines, they are ruining your constitution; I knew they would.'

"The Duke made no answer, but rang the bell violently for some seconds.

"'Bless my heart,' said I, 'it surely can't be that I 'm mistaken. It's not possible it wasn't your Grace.'

"'Who is this man?' said the Duke, as the servant appeared in answer to the bell. 'Who let him upstairs?'

"'Mr. Baggs, your Grace,' he said. 'He dined with your Grace at—'

"'Take him away, give him in charge to the police; the fellow must be punished for his insolence.'

"My head was whirling, and my faculties were all astray. I neither knew what I said, nor what happened after, save that I felt myself half led, half pushed, down the stairs I had mounted so confidently five minutes before, while the liveried rascal kept dinning into my ears some threats about two months' imprisonment and hard labor. Just as we were passing through the hall, however, the door of a front-parlor opened, and a gentleman in a very elegant dressing-gown stepped out. I had neither time nor inclination to mark his features,—my own case absorbed me too completely. 'I am an unlucky wretch,' said I, aloud. 'Nothing ever prospers with me.'

"'Cheer up, old boy,' said he of the dressing-gown: 'fortune will take another turn yet; but I do confess you hold miserable cards.'

"The voice as he spoke aroused me. I turned about, and there stood my companion at Chesterfield.

"'His Grace wants you, Mr. Cavendish,' said the footman, as he opened the door for me.

"'Let him go, Thomas,' said Mr. Cavendish. 'There's no harm in old Raggs.'

"'Isn't he the Duke?' gasped I, as he tripped upstairs without noticing me further.

"'The Duke,—no, bless your heart, he's his gentleman!'

"Here was an end of all my cherished hopes and dreams of patronage. The aristocratic leader of fashion, the great owner of palaces, the Whig autocrat, tumbled down into a creature that aired newspapers and scented pocket-handkerchiefs. Never tell me of the manners of the titled classes again. Here was a specimen that will satisfy my craving for a life long; and if the reflection be so strong, what must be the body which causes it!"

It is about two years since I was one of that strange and busy mob of some five hundred people who were assembled on the platform in the Euston-Square station a few minutes previous to the starting of the morning mail-train for Birmingham. To the unoccupied observer the scene might have been an amusing one; the little domestic incidents of leave-taking and embracing, the careful looking after luggage and parcels, the watchful anxieties for a lost cloak or a stray carpet-bag, blending with the affectionate farewells of parting, are all curious, while the studious preparation for comfort of the old gentleman in the coupé oddly contrast with similar arrangements on a more limited scale by the poor soldier's wife in the third-class carriage.

Small as the segment of humanity is, it is a type of the great world to which it belongs.

I sauntered carelessly along the boarded terrace, investigating, by the light of the guard's lantern, the inmates of the different carriages, and, calling to my assistance my tact as a physiognomist as to what party I should select for my fellow-passengers,—"Not in there, assuredly," said I to myself, as I saw the aquiline noses and dark eyes of two Hamburgh Jews; "nor here, either,—I cannot stand a day in a nursery; nor will this party suit me, that old gentleman is snoring already;" and so I walked on until at last I bethought me of an empty carriage, as at least possessing negative benefits, since positive ones were denied me. Scarcely had the churlish determination seized me, when the glare of the light fell upon the side of a bonnet of white lace, through whose transparent texture a singularly lovely profile could be seen. Features purely Greek in their character, tinged with a most delicate color, were defined by a dark mass of hair, worn in a deep band along the cheek almost to the chin. There was a sweetness, a look of guileless innocence, in the character of the face which, even by the flitting light of the lantern, struck me strongly. I made the guard halt, and peeped into the carriage as if seeking for a friend. By the uncertain flickering, I could detect the figure of a man, apparently a young one, by the lady's side; the carriage had no other traveller. "This will do," thought I, as I opened the door, and took my place on the opposite side.

Every traveller knows that locomotion must precede conversation; the veriest commonplace cannot be hazarded till the piston is in motion or the paddles are flapping. The word "Go on" is as much for the passengers as the vehicle, and the train and the tongues are set in movement together; as for myself, I have been long upon the road, and might travesty the words of our native poet, and say,—

"My home is on the highway."

I have therefore cultivated, and I trust with some success, the tact of divining the characters, condition, and rank of fellow-travellers,—the speculation on whose peculiarities has often served to wile away the tediousness of many a wearisome road and many an uninteresting journey.

The little lamp which hung aloft gave me but slight opportunity of prosecuting my favorite study on this occasion. All that I could trace was the outline of a young and delicately formed girl, enveloped in a cashmere shawl,—a slight and inadequate muffling for the road at such a season. The gentleman at her side was attired in what seemed a dress-coat, nor was he provided with any other defence against the cold of the morning.

Scarcely had I ascertained these two facts, when the lamp flared, flickered, and went out, leaving me to speculate on these vague but yet remarkable traits in the couple before me. "What can they be?" "Who are they?" "Where do they come from?" "Where are they going?" were all questions which naturally presented themselves to me in turn; yet every inquiry resolved itself into the one, "Why has she not a cloak, why has not he got a Petersham?" Long and patiently did I discuss these points with myself, and framed numerous hypotheses to account for the circumstances,—but still with comparatively little satisfaction, as objections presented themselves to each conclusion; and although, in turn, I had made him a runaway clerk from Coutts's, a Liverpool actor, a member of the swell-mob, and a bagman, yet I could not, for the life of me, include her in the category of such an individual's companions. Neither spoke, so that from their voices, that best of all tests, nothing could be learned.

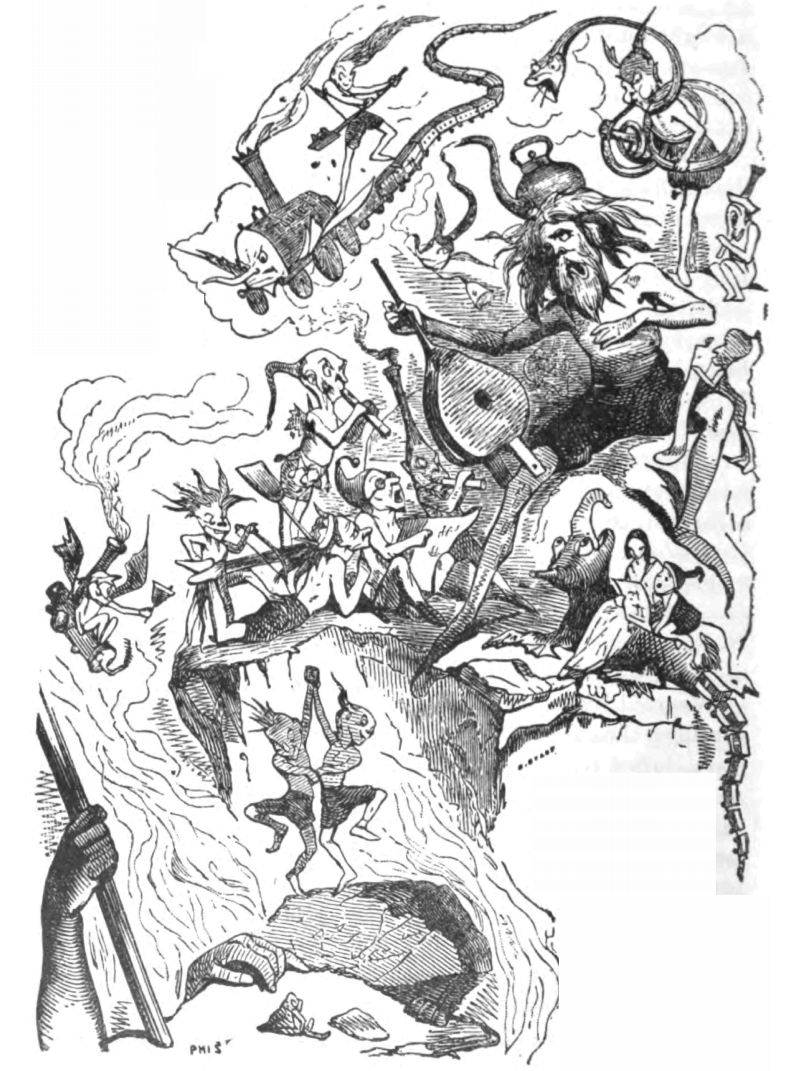

Wearied by my doubts, and worried by the interruption to my sleep the early rising necessitated, I fell soon into a sound doze, lulled by the soothing "strains" a locomotive so eminently is endowed with. The tremulous quavering of the carriage, the dull roll of the heavy wheels, the convulsive beating and heaving of the black monster itself, gave the tone to my sleeping thoughts, and my dreams were of the darkest. I thought that, in a gloomy silence, we were journeying over a wild and trackless plain, with no sight nor sound of man, save such as accompanied our sad procession; that dead and leafless trees were grouped about, and roofless dwellings and blackened walls marked the dreary earth; dark sluggish streams stole heavily past, with noisome weeds upon their surface; while along the sedgy banks sat leprous and glossy reptiles, glaring with round eyes upon us. Suddenly it seemed as if our speed increased; the earth and sky flew faster past, and objects became dim and indistinct; a misty maze of dark plain and clouded heaven were all I could discern; while straight in front, by the lurid glare of a fire fitted round and about two dark shapes danced a wild goblin measure, tossing their black limbs with frantic gesture, while they brandished in their hands bars of seething iron; one, larger and more dreadful than the other, sung in a "rauque" voice, that sounded like the clank of machinery, a rude song, beating time to the tune with his iron bar. The monotonous measure of the chant, which seldom varied in its note, sank deep into my chilled heart; and I think I hear still

THE SONG OF THE STOKER.

Rake, rake, rake,

Ashes, cinders, and coal;

The fire we make,

Must never slake,

Like the fire that roasts a soul.

Hurrah! my boys, 't is a glorious noise,

To list to the stormy main;

But nor wave-lash'd shore

Nor lion's roar

E'er equall'd a luggage train.

'Neath the panting sun our course we run,

No water to slake our thirst;

Nor ever a pool

Our tongue to cool,

Except the boiler burst.

The courser fast, the trumpet's blast,

Sigh after us in vain;

And even the wind

We leave behind

With the speed of a special train.

Swift we pass o'er the wild morass,

Tho' the night be starless and black;

Onward we go,

Where the snipe flies low,

Nor man dares follow our track.

A mile a minute, on we go,

Hurrah for my courser fast;

His coal-black mane,

And his fiery train,

And his breath—a furnace blast

On and on, till the day is gone,

We rush with a goblin scream;

And the cities, at night,

They start with affright,

At the cry of escaping steam.

Bang, bang, bang!

Shake, shiver, and throb;

The sound of our feet

Is the piston's beat,

And the opening valve our sob!

Our union-jack is the smoke-train black,

That thick from the funnel rolls;

And our bounding bark

Is a gloomy ark,

And our cargo—human souls.

Rake, rake, rake,

Ashes, cinders, and coal;

The fire we make,

Must never slake,

Like the fire that roasts a soul.

"Bang, bang, bang!" said I, aloud, repeating this infernal "refrain," and with an energy that made my two fellow-travellers burst out laughing. This awakened me from my sleep, and enabled me to throw off the fearful incubus which rested on my bosom; so strongly, however, was the image of my dream, so vivid the picture my mind had conjured up, and, stranger than all, so perfect was the memory of the demoniac song, that I could not help relating the whole vision, and repeating for my companions the words, as I have here done for the reader. As I proceeded in my narrative, I had ample time to observe the couple before me. The lady—for it is but suitable to begin with her—was young, she could scarcely have been more than twenty, and looked by the broad daylight even handsomer than by the glare of the guard's lantern; she was slight, but, as well as I could observe, her figure was very gracefully formed, and with a decided air of elegance detectable even in the ease and repose of her attitude. Her dress was of pale blue silk, around the collar of which she wore a profusion of rich lace, of what peculiar loom I am, unhappily, unable to say; nor would I allude to the circumstance, save that it formed one of the most embarrassing problems in my efforts at divining her rank and condition. Never was there such a travelling-costume; and although it suited perfectly the frail and delicate beauty of the wearer, it ill accorded with the dingy "conveniency" in which we journeyed. Even to her shoes and stockings (for I noticed these,—the feet were perfect) and gloves,—all the details of her dress had a freshness and propriety one rarely or ever sees encountering the wear and tear of the road. The young gentleman at her side—for he, too, was scarcely more than five-and-twenty, at most—was also attired in a costume as little like that of a traveller; a dress-coat and evening waistcoat, over which a profusion of chains were festooned in that mode so popular in our day, showed that he certainly, in arranging his costume, had other thoughts than of wasting such attractions on the desert air of a railroad journey. He was a good-looking young fellow, with that mixture of frankness and careless ease the youth of England so eminently possess, in contradistinction to the young men of other countries; his manner and voice both attested that he belonged to a good class, and the general courtesy of his demeanor showed one who had lived in society. While he evinced an evident desire to enter into conversation and amuse his companion, there was still an appearance of agitation and incertitude about him which showed that his mind was wandering very far from the topic before him. More than once he checked himself, in the course of some casual merriment, and became suddenly grave,—while from time to time he whispered to the young lady, with an appearance of anxiety and eagerness all his endeavors could not effectually conceal. She, too, seemed agitated,—but, I thought, less so than he; it might be, however, that from the habitual quietude of her manner, the traits of emotion were less detectable by a stranger. We had not journeyed far, when several new travellers entered the carriage, and thus broke up the little intercourse which had begun to be established between us. The new arrivals were amusing enough in their way,—there was a hearty old Quaker from Leeds, who was full of a dinner-party he had been at with Feargus O'Connor, the day before; there was an interesting young fellow who had obtained a fellowship at Cambridge, and was going down to visit his family; and lastly, a loud-talking, load-laughing member of the tail, in the highest possible spirits at the prospect of Irish politics, and exulting in the festivities he was about to witness at Derrynane Abbey, whither he was then proceeding with some other Danaïdes, to visit what Tom Steele calls "his august leader." My young friends, however, partook little in the amusement the newly arrived travellers afforded; they neither relished the broad, quaint common-sense of the Quaker, the conversational cleverness of the Cambridge man, or the pungent though somewhat coarse drollery of the "Emeralder." They sat either totally silent or conversing in a low, indistinct murmur, with their heads turned towards each other. The Quaker left us at Warwick, the "Fellow" took his leave soon after, and the O'Somebody was left behind at a station; the last thing I heard of him, being his frantic shouting as the train moved off, while he was endeavoring to swallow a glass of hot brandy and water. We were alone then once more; but somehow the interval which had occurred had chilled the warm current of our intercourse; perhaps, too, the effects of a long day's journey were telling on us all, and we felt that indisposition to converse which steals over even the most habitual traveller towards the close of a day on the road. Partly from these causes, and more strongly still from my dislike to obtrude conversation upon those whose minds were evidently preoccupied, I too lay back in my seat and indulged my own reflections in silence. I had sat for some time thus, I know not exactly how long, when the voice of the young lady struck on my ear; it was one of those sweet, tinkling silver sounds which somehow when heard, however slightly, have the effect at once to dissipate the dull routine of one's own thoughts, and suggest others more relative to the speaker.

"Had you not better ask him?" said she; "I am sure he can tell you." The youth apparently demurred, while she insisted the more, and at length, as if yielding to her entreaty, he suddenly turned towards me and said, "I am a perfect stranger here, and would feel obliged if you could inform me which is the best hotel in Liverpool." He made a slight pause and added, "I mean a quiet family hotel."

"I rarely stop in the town myself," replied I; "but when I do, to breakfast or dine, I take the Adelphi. I 'm sure you will find it very comfortable."

They again conversed for a few moments together; and the young man, with an appearance of some hesitation, said, "Do you mean to go there now, sir?"

"Yes," said I, "my intention is to take a hasty dinner before I start in the steamer for Ireland; I see by my watch I shall have ample time to do so, as we shall arrive full half an hour before our time."

Another pause, and another little discussion ensued, the only words of which I could catch from the young lady being, "I'm certain he will have no objection." Conceiving that these referred to myself, and guessing at their probable import, I immediately said, "If you will allow me to be your guide, I shall feel most happy to show you the way; we can obtain a carriage at the station, and proceed thither at once."

I was right in my surmise—both parties were profuse in their acknowledgments—the young man avowing that it was the very request he was about to make when I anticipated him. We arrived in due time at the station, and, having assisted my new acquaintances to alight, I found little difficulty in placing them in a carriage, for luggage they had none, neither portmanteau nor carpet-bag—not even a dressing-case—a circumstance at which, however, I might have endeavored to avoid expressing my wonder, they seemed to feel required an explanation at their hands; both looked confused and abashed, nor was it until by busying myself in the details of my own baggage, that I was enabled to relieve them from the embarrassment the circumstance occasioned.

"Here we are," said I: "this is the Adelphi," as we stopped at that comfortable and hospitable portal, through which the fumes of brown gravy and ox-tail float with a savory odor as pleasant to him who enters with dinner intentions as it is tantalizing to the listless wanderer without.

The lady thanked me with a smile, as I handed her into the house, and a very sweet smile too, and one I could have fancied the young man would have felt a little jealous of, if I had not seen the ten times more fascinating one she bestowed on him.

The young man acknowledged my slight service with thanks, and made a half gesture to shake hands at parting, which, though a failure, I rather liked, as evidencing, even in its awkwardness, a kindness of disposition—for so it is. Gratitude smacks poorly when expressed in trim and measured phrase; it seems not the natural coinage of the heart when the impression betrays too clearly the mint of the mind.

"Good-bye," said I, as I watched their retiring figures up the wide staircase. "She is devilish pretty; and what a good figure! I did not think any other than a French woman could adjust her shawl in that fashion." And with these very soothing reflections I betook myself to the coffee-room, and soon was deep in discussing the distinctive merits of mulligatawny, mock-turtle, or mutton chops, or listening to that everlasting paean every waiter in England sings in praise of the "joint."

In all the luxury of my own little table, with my own little salt-cellar, my own cruet-stand, my beer-glass, and its younger brother for wine, I sat awaiting the arrival of my fare, and puzzling my brain as to the unknown travellers. Now, had they been but clothed in the ordinary fashion of the road,—if the lady had worn a plaid cloak and a beaver bonnet,—if the gentleman had a brown Taglioui and a cloth cap, with a cigar-case peeping out of his breast-pocket, like everybody else in this smoky world,—had they but the ordinary allowance of trunks and boxes,—I should have been coolly conning over the leading article of the "Times," or enjoying the spicy leader in the last "Examiner;" but, no,—they had shrouded themselves in a mystery, though not in garments; and the result was that I, gifted with that inquiring spirit which Paul Pry informs us is the characteristic of the age, actually tortured myself into a fever as to who and what they might be,—the origin, the course, and the probable termination of their present adventure,—for an adventure I determined it must be. "People do such odd things nowadays," said I, "there's no knowing what the deuce they may be at. I wish I even knew their names, for I am certain I shall read to-morrow or the next day in the second column of the 'Times,' 'Why will not W. P. and C. P. return to their afflicted friends? Write at least,—write to your bereaved parents, No. 12 Russell Square;' or, 'If F. M. S. will not inform her mother whither she has gone, the deaths of more than two of the family will be the consequence.'" Now, could I only find out their names, I could relieve so much family apprehension—Here comes the soup, however,—admirable relief to a worried brain! how every mouthful swamps reflection!—even the platitude of the waiter's face is, as the Methodists say, "a blessed privilege," so agreeably does it divest the mind of a thought the more, and suggest that pleasant vacuity so essential to the hour of dinner. The tureen was gone, and then came one of those strange intervals which all taverns bestow, as if to test the extent of endurance and patience of their guests.

My thoughts turned at once to their old track. "I have it," said I, as a bloody-minded suggestion shot through my brain. "This is an affair of charcoal and oxalic acid, this is some damnable device of arsenic or sugar-of-lead,—these young wretches have come down here to poison themselves, and be smothered in that mode latterly introduced among us. There will be a double-locked door and smell of carbonic gas through the key-hole in the morning. I have it all before me, even to the maudlin letter, with its twenty-one verses of maudlin poetry at the foot of it. I think I hear the coroner's charge, and see the three shillings and eightpence halfpenny produced before the jury, that were found in the youth's possession, together with a small key and a bill for a luncheon at Birmingham. By Jove, I will prevent it, though; I will spoil their fun this time; if they will have physic, let them have something just as nauseous, but not so injurious. My own notion is a basin of this soup and a slice of the 'joint,' and here it comes;" and thus my meditations were again destined to be cut short, and revery give way to reality.

I was just helping myself to my second slice of mutton, when the young man entered the coffee-room, and walked towards me. At first his manner evinced hesitation and indecision, and he turned to the fireplace, as if with some change of purpose; then, as if suddenly summoning his resolution, he came up to the table at which I sat, and said,—

"Will you favor me with five minutes of your time?"

"By all means," said I; "sit down here, and I'm your man; you must excuse me, though, if I proceed with my dinner, as I see it is past six o'clock, and the packet sails at seven."

"Pray, proceed," replied he; "your doing so will in part excuse the liberty I take in obtruding myself upon you."

He paused, and although I waited for him to resume, he appeared in no humor to do so, but seemed more confused than before.

"Hang it," said he at length, "I am a very bungling negotiator, and never in my life could manage a matter of any difficulty."

"Take a glass of sherry," said I; "try if that may not assist to recall your faculties."

"No, no," cried he; "I have taken a bottle of it already, and, by Jove, I rather think my head is only the more addled. Do you know that I am in a most confounded scrape. I have run away with that young lady; we were at an evening-party last night together, and came straight away from the supper-table to the train."

"Indeed!" said I, laying down my knife and fork, not a little gratified that I was at length to learn the secret that had so long teased me. "And so you have run away with her!"

"Yes; it was no sudden thought, however,—at least, it was an old attachment; I have known her these two months."

"Oh! oh!" said I; "then there was prudence in the affair."

"Perhaps you will say so," said he, quickly, "when I tell you she has £30,000 in the Funds, and something like £1700 a year besides,—not that I care a straw for the money, but, in the eye of the world, that kind of thing has its éclat."

"So it has," said I, "and a very pretty éclat it is, and one that, somehow or another, preserves its attractions much longer than most surprises; but I do not see the scrape, after all."

"I am coming to that," said he, glancing timidly around the room. "The affair occurred this wise: we were at an evening-party,—a kind of déjeûné, it was, on the Thames,—Charlotte came with her aunt,—a shrewish old damsel, that has no love for me; in fact, she very soon saw my game, and resolved to thwart it. Well, of course I was obliged to be most circumspect, and did not venture to approach her, not even to ask her to dance, the whole evening. As it grew late, however, I either became more courageous or less cautious, and I did ask her for a waltz. The old lady bristled up at once, and asked for her shawl. Charlotte accepted my invitation, and said she would certainly not retire so early; and I, to cut the matter short, led her to the top of the room. We waltzed together, and then had a 'gallop,' and after that some champagne, and then another waltz; for Charlotte was resolved to give the old lady a lesson,—she has spirit for anything! Well, it was growing late by this time, and we went in search of the aunt at last; but, by Jove! she was not to be found. We hunted everywhere for her, looked well in every corner of the supper-room, where it was most likely we should discover her; and at length, to our mutual horror and dismay, we learned that she had ordered the carriage up a full hour before, and gone off, declaring that she would send Charlotte's father to fetch her home, as she herself possessed no influence over her. Here was a pretty business,—the old gentleman being, as Charlotte often told me, the most choleric man in England. He had killed two brother officers in duels, and narrowly escaped being hanged at Maidstone for shooting a waiter who delayed bringing him the water to shave,—a pleasant old boy to encounter on such an occasion at this!

"'He will certainly shoot me,—he will shoot you,—he will kill us both!' were the only words she could utter; and my blood actually froze at the prospect before us. You may smile if you like; but let me tell you that an outraged father, with a pair of patent revolving pistols, is no laughing matter. There was nothing for it, then, but to 'bolt.' She saw that as soon as I did; and although she endeavored to persuade me to suffer her to return home alone, that, you know, I never could think of; and so, after some little demurrings, some tears, and some resistance, we got to the Euston-Square station, just as the train was going. You may easily think that neither of us had much time for preparation. As for myself, I have come away with a ten-pound note in my purse,—not a shilling more have I in my possession; and here we are now, half of that sum spent already, and how we are to get on to the North, I cannot for the life of me conceive."

"Oh! that's it," said I, peering at him shrewdly from under my eyelids.

"Yes, that 's it; don't you think it is bad enough?" and he spoke the words with a reckless frankness that satisfied all my scruples. "I ought to tell you," said he, "that my name is Blunden; I am lieutenant in the Buffs, on leave; and now that you know my secret, will you lend me twenty pounds? which perhaps, may be enough to carry us forward,—at least, it will do, until it will be safe for me to write for money."

"But what would bring you to the North?" said I; "why not put yourselves on board the mail-packet this evening, and come to Dublin? We will marry you there just as cheaply; pursuit of you will be just as difficult; and I 'd venture to say, you might choose a worse land for the honeymoon."

"But I have no money," said he; "you forgot that."

"For the matter of money," said I, "make your mind easy. If the young lady is going away with her own consent,—if, indeed, she is as anxious to get married as you are,—make me the banker, and I 'll give her away, be the bridesmaid, or anything else you please."

"You are a trump," said he, helping himself to another glass of my sherry; and then filling out a third, which emptied the bottle, he slapped me on the shoulder, and said, "Here 's your health; now come upstairs."

"Stop a moment," said I, "I must see her alone,—there must be no tampering with the evidence."

He hesitated for a second, and surveyed me from head to foot; and whether it was the number of my double chins or the rotundity of my waistcoat divested his mind of any jealous scruples, but he smiled coolly, and said, "So you shall, old buck,—we will never quarrel about that."

Upstairs we went accordingly, and into a handsome drawing-room on the first floor, at one end of which, with her head buried in her hands, the young lady was sitting.

"Charlotte," said he, "this gentleman is kind enough to take an interest in our fortunes, but he desires a few words with you alone."

I waved my hand to him to prevent his making any further explanation, and as a signal to withdraw; he took the hint and left the room.

Now, thought I, this is the second act of the drama; what the deuce am I to do here? In the first place, some might deem it my duty to admonish the young damsel on the impropriety of the step, to draw an afflicting picture of her family, to make her weep bitter tears, and end by persuading her to take a first-class ticket in the up-train. This would be the grand parento-moral line; and I shame to confess it, it was never my forte. Secondly, I might pursue the inquiry suggested by myself, and ascertain her real sentiments. This might be called the amico-auxiliary line. Or, lastly, I might try a little, what might be done on my own score, and not see £30,000 and £1700 a year squandered by a cigar-smoking lieutenant in the Buffs. As there may be different opinions about this line, I shall not give it a name. Suffice it to say, that, notwithstanding a sly peep at as pretty a throat and as well rounded an instep as ever tempted a "government Mercury," I was true to my trust, and opened the negotiation on the honest footing.

"Do you love him, my little darling?" said I; for somehow consolation always struck me as own-brother to love-making. It is like indorsing a bill for a friend, which, though he tells you he 'll meet, you always feel responsible for the money.

She turned upon me an arch look. By St. Patrick, I half regretted I had not tried number three, as in the sweetest imaginable voice she said,—

"Do you doubt it?"

"I wish I could," thought I to myself. No matter, it was too late for regrets; and so I ascertained, in a very few minutes, that she corroborated every portion of the statement, and was as deeply interested in the success of the adventure as himself.

"That will do," said I. "He is a lucky fellow,—I always heard the Buffs were;" and with that I descended to the coffee-room, where the young man awaited me with the greatest anxiety.

"Are you satisfied?" cried he, as I entered the room.

"Perfectly," was my answer. "And now let us lose no more time; it wants but a quarter to seven, and we must be on board in ten minutes."

As I have already remarked, my fellow-travellers were not burdened with luggage, so there was little difficulty in expediting their departure; and in half an hour from that time we were gliding down the Mersey, and gazing on the spangled lamps which glittered over that great city of soap, sugar, and sassafras, train-oil, timber, and tallow. The young lady soon went below, as the night was chilly; but Blunden and myself walked the deck until near twelve o'clock, chatting over whatever came uppermost, and giving me an opportunity to perceive that, without possessing any remarkable ability or cleverness, he was one of those offhand, candid, clear-headed young fellows, who, when trained in the admirable discipline of the mess, become the excellent specimens of well-conducted, well-mannered gentlemen our army abounds with.

We arrived in due course in Dublin. I took my friends up to Morrison's, drove with them after breakfast to a fashionable milliner's, where the young lady, with an admirable taste, selected such articles of dress as she cared for, and I then saw them duly married. I do not mean to say that the ceremony was performed by a bishop, or that a royal duke gave her away; neither can I state that the train of carriages comprised the equipages of the leading nobility. I only vouch for the fact that a little man, with a black eye and a sinister countenance, read a ceremony of his own composing, and made them write their names in a great book, and pay thirty shillings for his services; after which I put a fifty-pound note into Blunden's hand, saluted the bride, and, wishing them every health and happiness, took my leave.

They started at once with four posters for the North, intending to cross over to Scotland. My engagements induced me to leave town for Cork, and in less than a fortnight I found at my club a letter from Blunden, enclosing the fifty pounds, with a thousand thanks for my prompt kindness, and innumerable affectionate reminiscences from Madame. They were as happy as—confound it, every one is happy for a week or a fortnight; so I crushed the letter, pitched it into the fire, was rather pleased with myself for what I had done, and thought no more of the whole transaction.

Here then my tale should have an end, and the moral is obvious. Indeed, I am not certain but some may prefer it to that which the succeeding portion conveys, thinking that the codicil revokes the body of the testament. However that may be, here goes for it.

It was about a year after this adventure that I made one of a party of six travelling up to London by the "Grand Junction." The company were chatty, pleasant folk, and the conversation, as often happens among utter strangers, became anecdotic; many good stories were told in turn, and many pleasant comments made on them, when at length it occurred to me to mention the somewhat singular rencontre I have already narrated as having happened to myself.

"Strange enough," said I, "the last time I journeyed along this line, nearly this time last year, a very remarkable occurrence took place. I happened to fall in with a young officer of the Buffs, eloping with an exceedingly pretty girl; she had a large fortune, and was in every respect a great 'catch;' he ran away with her from an evening party, and never remembered, until he arrived at Liverpool, that he had no money for the journey. In this dilemma, the young fellow, rather spooney about the whole thing, I think would have gone quietly back by the next train, but, by Jove, I could n't satisfy my conscience that so lovely a girl should be treated in such a manner. I rallied his courage; took him over to Ireland in the packet, and got them married the next morning."

"Have I caught you at last, you old, meddling scoundrel!" cried a voice, hoarse and discordant with passion, from the opposite side; and at the same instant a short, thickset old man, with shoulders like a Hercules, sprung at me. With one hand he clutched me by the throat, and with the other he pummelled my head against the panel of the conveyance, and with such violence that many people in the next carriage averred that they thought we had run into the down train. So sudden was the old wretch's attack, and so infuriate withal, it took the united force of the other passengers to detach him from my neck; and even then, as they drew him off, he kicked at me like a demon. Never has it been my lot to witness such an outbreak of wrath; and, indeed, were I to judge from the symptoms it occasioned, the old fellow had better not repeat it, or assuredly apoplexy would follow.

"That villain,—that old ruffian," said he, glaring at me with flashing eyeballs, while he menaced me with his closed fist,—"that cursed, meddling scoundrel is the cause of the greatest calamity of my life."

"Are you her father, then?" articulated I, faintly, for a misgiving came over me that my boasted benevolence might prove a mistake. "Are you her father?" The words were not out, when he dashed at me once more, and were it not for the watchfulness of the others, inevitably had finished me.

"I've heard of you, my old buck," said I, affecting a degree of ease and security my heart sadly belied. "I 've heard of your dreadful temper already,—I know you can't control yourself. I know all about the waiter at Maidstone. By Jove, they did not wrong you; and I am not surprised at your poor daughter leaving you—" But he would not suffer me to conclude; and once more his wrath boiled over, and all the efforts of the others were barely sufficient to calm him into a semblance of reason.

There would be an end to my narrative if I endeavored to convey to my reader the scene which followed, or recount the various outbreaks of passion which ever and anon interrupted the old man, and induced him to diverge into sundry little by-ways of lamentation over his misfortune, and curses upon my meddling interference. Indeed his whole narrative was conducted more in the staccato style of an Italian opera father than in the homely wrath of an English parent; the wind-up of these dissertations being always to the one purpose, as with a look of scowling passion directed towards me, he said, "Only wait till we reach the station, and see if I won't do for you."

His tale, in few words, amounted to this. He was the Squire Blunden,—the father of the lieutenant in the "Buffs." The youth had formed an attachment to a lady whom he had accidentally met in a Margate steamer. The circumstances of her family and fortune were communicated to him in confidence by herself; and although she expressed her conviction of the utter impossibility of obtaining her father's consent to an untitled match, she as resolutely refused to elope with him. The result, however, was as we have seen; she did elope,—was married,—they made a wedding tour in the Highlands, and returned to Blunden Hall two months after, where the old gentleman welcomed them with affection and forgiveness. About a fortnight after their return, it was deemed necessary to make inquiry as to the circumstances of her estate and funded property, when the young lady fell upon her knees, wept bitterly, said she had not a sixpence,—that the whole thing was a "ruse;" that she had paid five pounds for a choleric father, three ten for an aunt warranted to wear "satin;" in fact, that she had been twice married before, and had heavy misgivings that the husbands were still living.

There was nothing left for it but compromise. "I gave her," said he, "five hundred pounds to go to the devil, and I registered, the same day, a solemn oath that if ever I met this same Tramp, he should carry the impress of my knuckles on his face to the day of his death."

The train reached Harrow as the old gentleman spoke. I waited until it was again in motion, and, flinging wide the door, I sprang out, and from that day to this have strictly avoided forming acquaintance with a white lace bonnet, even at a distance, or ever befriending a lieutenant in the Buffs.

I got into the Dover "down train" at the station, and after seeking for a place in two or three of the leading carriages, at last succeeded in obtaining one where there were only two other passengers. These were a lady and a gentleman,—the former, a young, pleasing-looking girl, dressed in quiet mourning; the latter was a tall, gaunt, bilious-looking man, with grisly gray hair, and an extravagantly aquiline nose. I guessed, from the positions they occupied in the carriage, that they were not acquaintances, and my conjecture proved subsequently true. The young lady was pale, like one in delicate health, and seemed very weary and tired, for she was fast asleep as I entered the carriage, and did not awake, notwithstanding all the riot and disturbance incident to the station. I took my place directly in front of my fellow-travellers; and whether from mere accident, or from the passing interest a pretty face inspires, cast my eyes towards the lady; the gaunt man opposite fixed on me a look of inexpressible shrewdness, and with a very solemn shake of his head, whispered in a low undertone,—

"No! no! not a bit of it; she ain't asleep,—they never do sleep,—never!"

"Oh!" thought I to myself, "there's another class of people not remarkable for over-drowsiness; "for, to say truth, the expression of the speaker's face and the oddity of his words made me suspect that he was not a miracle of sanity. The reflection had scarcely passed through my mind, when he arose softly from his seat, and assumed a place beside me.