The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Origins and Destiny of Imperial Britain, by

J. A. Cramb

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Origins and Destiny of Imperial Britain

Nineteenth Century Europe

Author: J. A. Cramb

Release Date: December 19, 2009 [EBook #30710]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ORIGINS, DESTINY--IMPERIAL BRITAIN ***

Produced by Al Haines

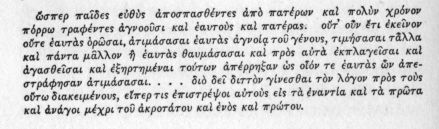

[Transcriber's note: transliterated Greek is surrounded by plus signs, e.g. "+agôníai+".]

"For the noveltie and strangenesse of the matter which I determine and deliberate to entreat upon, is of efficacie and force enough to draw the mindes both of young and olde to the diligent reading and digesting of these labours. For what man is there so despising knowledge, or any so idle and slothfull to be found, which will eschew or avoide by what policies or by what kinde of government the most part of nations in the universall world were vanquished, subdued and made subject unto the one empire of the Romanes, which before that time was never seen or heard? Or who is there that hath such earnest affection to other discipline or studie, that he suposeth any kind of knowledge to be of more value or worthy to be esteemed before this?"

The Histories of the most famous Chronographer, POLYBIUS.

(Englished by C. W., and imprinted at London, Anno 1568).

The following pages are a reprint of a course of lectures delivered in May, June, and July, 1900. Their immediate inspiration was the war in South Africa (two of the lectures deal directly with that war), but in these pages, written fifteen years ago, will be found foreshadowed the ideals and deeds of the present hour. When the book first appeared, Mr. Cramb wrote that he "had been induced to publish these reflections by the belief or the hope that at the present grave crisis they might not be without service to his country." In the same hope his lectures are now reprinted.

John Adam Cramb was born at Denny, in Scotland, on the 4th of May, 1862. On leaving school he went to Glasgow University, where he graduated in 1885, taking 1st Class Honours in Classics. In the same year he was appointed to the Luke Fellowship in English Literature. He also studied at Bonn University. He subsequently travelled on the Continent, and in 1887 married the third daughter of the late Mr. Edward W. Selby Lowndes of Winslow, and left one son. From 1888 to 1890 he was Lecturer in Modern History at Queen Margaret College, Glasgow. Settling in London in 1890 he contributed several articles to the Dictionary of National Biography, and also occasional reviews to periodicals. For many years he was an examiner for the Civil Service Commission. In 1892 he was appointed Lecturer and in 1893 Professor of Modern History at Queen's College, London, where he lectured until his death. He was also an occasional lecturer on military history at the Staff College, Camberley, and at York, Chatham, and other centres. In London he gave private courses on history, literature, and philosophy. His last series of lectures was delivered in February and March, 1913, the subject being the relations between England and Germany. In response to many requests he was engaged in preparing these lectures for publication when, in October, 1913, he died.

The present age has rewritten the annals of the world, and set its own impress on the traditions of humanity. In no period has the burden of the past weighed so heavily upon the present, or the interpretation of its speculative import troubled the heart so profoundly, so intimately, so monotonously.

How remote we stand from the times when Raleigh could sit down in the Tower, and with less anxiety about his documents, State records, or stone monuments than would now be imperative in compiling the history of a county, proceed to write the History of the World! And in speculation it is the Tale, the fabula, the procession of impressive incidents and personages, which enthralls him, and with perfect fitness he closes his work with the noblest Invocation to Death that literature possesses. But beneath the variety or pathos of the Tale the present age ever apprehends a deeper meaning, or is oppressed by a sense of mystery, of wonder, or of sorrow unrevealed, which defies tears.

This revolution in our conception of History, this boundless industry which in Germany, France, England, Italy, has led to the printing of mountains of forgotten memoirs, correspondences, State papers, this endless sifting of evidence, this treasuring above riches of the slight results slowly and patiently drawn, is neither accident, nor transient caprice, nor antiquarian frenzy, but a phase of the guiding impulse, the supreme instinct of this age—the ardour to know all, to experience all, to be all, to suffer all, in a word, to know the Truth of things—if haply there come with it immortal life, even if there come with it silence and utter death. The deepened significance of history springs thus from the deepened significance of life, and the passion of our interest in the past from the passion of our interest in the present. The half-effaced image on a coin, the illuminated margin of a mediaeval manuscript, the smile on a fading picture—if these have become, as it were, fountains of unstable reveries, perpetuating the Wonder which is greater than Knowledge, it is a power from the present that invests them with this magic. Life has become more self-conscious; not of the narrow self merely, but of that deeper Self, the mystic Presence which works behind the veil.

World-history is no more the fairy tale whose end is death, but laden with eternal meanings, significances, intimations, swift gleams of the Timeless manifesting itself in Time. And the distinguishing function of History as a science lies in its ceaseless effort not only to lay bare, to crystallize the moments of all these manifestations, but to discover their connecting bond, the ties that unite them to each other and to the One, the hidden source of these varied manifestations, whether revealed as transcendent thought, art, or action.

Hence, as in prosecuting elsewhere our inquiry into the origin of the French Monarchy or the decline of oligarchic Venice, we examined not only the characters, incidents, policies immediately connected with the subject, but attempted an answer to the question—What is the place of these incidents in the universal scheme of things? so in the treatment of the theme now before us, the origins of Imperial Britain, pursuing a similar plan, we have to consider not merely the relations of Imperial Britain to the England and Scotland of earlier times, but its relations to mediaeval Europe, and to determine so far as is possible its place amongst the world-empires of the past. I use the phrase "Imperial Britain," and not "British Empire," because from the latter territorial associations are inseparable. It designates India, Canada, Egypt, and the like. But by "Imperial Britain" I wish to indicate the informing spirit, the unseen force from within the race itself, which in the past has shapen and in the present continues to shape this outward, this material frame of empire. With the rise of this spirit, this consciousness within the British race of its destiny as an imperial people, no event in recent history can fitly be compared. The unity of Germany under the Hohenzollern is an imposing, a far-reaching achievement. The aspirations of the period of the Aufklärung—Lessing, Schiller, Arndt, and Fichte—find in this edifice their political realization. But the incident is not unprecedented. Even the writings of Friedrich Gentz are not by it made obsolete. It has affected the European State-system as the sudden unity of Spain under Ferdinand or the completion of the French Monarchy under Louis XIV affected it. But in this unobserved, this silent growth of Imperial Britain—so unobserved that it presents itself even now as an unreal, a transient thing—a force intrudes into the State-systems of the world which, whether we view it in its effects upon the present age or seek to gauge its significance to the future, has few, if any, parallels in history.

What is the nature of this Consciousness? What is its historical basis? Is it possible to trace the process by which it has emerged?

In the history of every conscious organism, a race, a State, or an individual, there is a certain moment when the Unconscious desire, purpose, or ideal passes into the Conscious. Life's end is then manifest. The ideal unsuspected hitherto, or dimly discerned, now becomes the fixed law of existence. Such moments inevitably are difficult to localize. Bonaparte in 1793 fascinates the younger Robespierre—"He has so much of the future in his mind." But it is neither Toulon, nor Vendémiaire, nor Lodi, but the marshes of Arcola, two years after Robespierre has fallen on the scaffold, that reveal Napoleon to himself. So Diderot perceives the true bent of Rousseau's genius long before the Dijon essay reveals it to the latter himself and to France. Polybius discovers in the war of Regulus and of Mylae the beginning of Rome's imperial career, but a juster instinct leads Livy to devote his most splendid paragraphs to the heroism in defeat of Thrasymene and Cannae. It was the singular fate of Camoens to voice the ideal of his race, to witness its glory, and to survive its fall. The prose of Osorius[1] does but prolong the echoes of Camoens' mighty line. Within a single generation, Portugal traces the bounds of a world-empire, great and impressive; the next can hardly discover the traces. But to the limning of that sketch all the past of Portugal was necessary, though then it emerged for the first time from the Unconscious to the Conscious. Similarly in the England of the seventeenth century the conscious deliberate resolve to be itself the master of its fate takes complete possession of the nation. This is the ideal which gives essential meaning to the Petition of Right, to the Grand Remonstrance, to the return at the Restoration to the "principles of 1640"; it is this which gives a common purpose to the lives of Eliot, Pym, Shaftesbury, and Somers. It is the unifying motive of the politics of the whole seventeenth century. The eighteenth expands or curtails this, but originates nothing. An ideal from the past controls the genius of the greatest statesmen of the eighteenth century. But from the closing years of the century to the present hour another ideal, at first existing unperceived side by side with the former, has slowly but insensibly advanced, obscure in its origins and little regarded in its first developments, but now impressing the whole earth by its majesty—the Ideal of Imperial Britain.

It is vain or misleading for the most part to fix precisely the first beginnings of great movements in history. Nevertheless it is often convenient to select for special study even arbitrarily some incident or character in which that movement first conspicuously displays itself. And if the question were asked—When does monarchical or constitutional England first distinctively pass into Imperial Britain? I should point to the close of the eighteenth century, to the heroic patience with which the twenty-two years' war against France was borne, hard upon the disaster of Yorktown and the loss of an empire; and further, if you proceeded to search in speculative politics or actual speeches for a deliberate expression of this transition, I should select as a conspicuous instance Edmund Burke's great impeachment of Warren Hastings. There this first awakening consciousness of an Imperial destiny declares itself in a very dramatic and pronounced form indeed. Yet Burke's range in speculative politics, compared with that of such a writer as Montesquieu, is narrow. His conception of history at its highest is but an anticipation of the picturesque but pragmatic school of which Macaulay is coryphaeus. In religion he revered the traditions, and acquiesced in the commonplaces of his time. His literary sympathies were less varied, his taste less sure than those of Charles James Fox. In constitutional politics he clung obstinately to the ideals of the past; to Parliamentary reform he was hostile or indifferent. As Pitt was the first great statesman of the nineteenth century, so Burke was the last of the great statesmen of the seventeenth century; for it is to the era of Pym and of Shaftesbury that, in his constitutional theories, Burke strictly belongs. But if his range was narrow, he is master there. "Within that circle none durst walk but he." No cause in world-history has inspired a nobler rhetoric, a mightier language. And if he is a reactionary in constitutional politics, in his impeachment of Hastings he is the prophet of a new era, the annunciator of an ideal which the later nineteenth century slowly endeavours to realize—an empire resting not on violence, but on justice and freedom. This ideal influences the action, the policy, of statesmen earlier in the century; but in Chatham its precise character, that which differentiates the ideal of Britain from that, say, of Rome, is less clear than in Burke. And in the seventeenth century, unless in a latent unconscious form, it can hardly be traced at all. In the speculative politics of that century we encounter it again and again; but in practical politics it has no part. I could not agree with Lord Rosebery when in an address he spoke of Cromwell as "a great Briton." Cromwell is a great Englishman, but neither in his actions nor in his policy, neither in his letters, nor in any recorded utterance, public or private, does he evince definite sympathy with, or clear consciousness of the distinctive ideal of Imperial Britain. His work indeed leads towards this end, as the work of Raleigh, of the elder Essex, or of Grenville, leads towards it, but not consciously, not deliberately.

In Burke, however, and in his younger contemporaries, the conscious influence, the formative power of a higher ideal, of wider aspirations than moulded the actual statesmanship of the past, can no longer escape us. The Empire is being formed, its material bounds marked out, here definitely, there lost in receding vistas. On the battlefield or in the senate-house, or at the counter of merchant adventurers, this work is slowly elaborating itself. And within the nation at large the ideal which is to be the spirit, the life of the Empire is rising into ever clearer consciousness. Its influence throws a light upon the last speeches of the younger Pitt. If the Impeachment be Burke's chef d'oeuvre, Pitt never reached a mightier close than in the speech which ended as the first grey light touched the eastern windows of Westminster, suggesting on the instant one of the happiest and most pathetic quotations ever made within those walls.[2] The ideal makes great the life of Wilberforce; it exalts Canning; and Clarkson, Romilly, Cobbett, Bentham is each in his way its exponent. "The Cry of the Children" derived an added poignancy from the wider pity which, after errors and failures more terrible than crimes, extended itself to the suffering in the Indian village, in the African forest, or by the Nile. The Chartist demanded the Rights of Englishmen, and found the strength of his demand not diminished, but heightened, by the elder battle-cry of the "Rights of Man." Thus has this ideal, grown conscious, gradually penetrated every phase of our public life. It removes the disabilities of religion; enfranchises the millions, that they by being free may bring freedom to others. In the great renunciation of 1846 it borrows a page from Roman annals, and sets the name of Peel with that of Caius Gracchus. It imparts to modern politics an inspiration and a high-erected effort, the power to falter at no sacrifice, dread no responsibility.

Thus, then, as in the seventeenth century the ideal of national and constituted freedom takes complete possession of the English people, so in the nineteenth this ideal of Imperial Britain, risen at last from the sphere of the Unconscious to the Conscious, has gradually taken possession of all the avenues and passages of the Empire's life, till at the century's close there is not a man capable of sympathies beyond his individual walk whom it does not strengthen and uplift.

Definitions are perilous, yet we must now attempt to define this ideal, to frame an answer to the question—What is the nature of this ideal which has thus arisen, of this Imperialism which is insensibly but surely taking the place of the narrower patriotism of England, of Scotland, and of Ireland? Imperialism, I should say, is patriotism transfigured by a light from the aspirations of universal humanity; it is the passion of Marathon, of Flodden or Trafalgar, the ardour of a de Montfort or a Grenville, intensified to a serener flame by the ideals of a Condorcet, a Shelley, or a Fichte. This is the ideal, and in the resolution deliberate and conscious to realize this ideal throughout its dominions, from bound to bound, in the voluntary submission to this as to the primal law of its being, lies what may be named the destiny of Imperial Britain.

As the artist by the very law of his being is compelled to body forth his conceptions in colour, in words, or in marble, so the race dowered with the genius for empire is compelled to dare all, to suffer all, to sacrifice all for the fulfilment of its fate-appointed task. This is the distinction, this the characteristic of the empires, the imperial races of the past, of the remote, the shadowy empires of Media, of Assyria, of the nearer empires of Persia, Macedon, and Rome. To spread the name, and with the name the attributes, the civilizing power of Hellas, throughout the world is the ideal of Macedon. Similarly of Rome: to subdue the world, to establish there her peace, governing all in justice, marks the Rome of Julius, of Vespasian, of Trajan. And in this measureless devotion to a cause, in this surplus energy, and the necessity of realizing its ideals in other races, in other peoples, lies the distinction of the Imperial State, whether city or nation. The origin of these characteristics in British Imperialism we shall examine in a later lecture.

Let me now endeavour to set the distinctive ideal of Britain before you in a clearer light. Observe, first of all, that it is essentially British. It is not Roman, not Hellenic. The Roman ideal moulds every form of Imperialism in Europe, and even to a certain degree in the East, down to the eighteenth century. The theory of the mediaeval empire derives immediately from Rome. The Roman justice disguised as righteousness easily warrants persecution, papal or imperial. The Revocation of the Edict of Passau by a Hapsburg, and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by a Bourbon, trace their origin without a break to that emperor to whom Dante assigns so great a part in the Paradiso.[3] Lord Beaconsfield, with the levity in matters of scholarship which he sometimes displayed, once ascribed the phrase imperium ac libertas to a Roman historian. The voluntary or accidental error is nothing; but the conception of Roman Imperialism which it popularized is worth considering. It is false to the genius of Rome. It is not that the phrase nowhere occurs in a Roman historian; but no statesman, no Roman historian, not Sulla, not Caesar, nor Marcus, could ever have bracketed these words. Imperium ac justitia he might have said; but he could never have used together the conceptions of Empire and Freedom. The peoples subdued by Rome—Spain, Gaul, Africa—received from Rome justice, and for this gift blessed Rome's name, deifying her genius. But the ideal of Freedom, the freedom that allows or secures for every soul the power to move in the highest path of its being, this is no pre-occupation of a Roman statesman! Yet it is in this ideal of freedom that the distinction, or at least a distinction of Modern, as opposed to Roman or Hellenic, Europe consists; in the effort, that is to say, to spiritualize the conception of outward justice, of outward freedom, to rescue individual life from the incubus of the State, transfiguring the State itself by the larger freedom, the higher justice, which Sophocles seeks in vain throughout Hellas, which Virgil in Rome can nowhere find. The common traits in the Kreon of tragedy and the Kritias of history, in the hero of the Aeneid and the triumvir Octavianus, are not accident, but arise from the revolt of the higher freedom of Art, conscious or unconscious, against the essential egoism of the wrong masking as right of the ancient State. And it is in the Empire of Britain that this effort of Modern Europe is realized, not only in the highest, but in the most original and varied forms. The power of the Roman ideal, on the other hand, saps the preceding empires of Modern Europe down to the seventeenth century, the empire of the German Caesars, the Papacy itself, Venice, Spain, Bourbon France. Consider how completely the ideals of these States are enshrined in the De Monarchia, and how closely the De Monarchia knits itself to Caesarian and to consular Rome!

The political history of Venice, stripped of its tinsel and melodrama, is tedious as a twice-told tale. Her art, her palaces, are her own eternally, a treasury inexhaustible as the light and mystery of the waters upon which she rests like a lily, the changeful element multiplying her structured loveliness and the opalescent hues of her sky. But in politics Venice has not enriched the world with a single inspiring thought which Rome had not centuries earlier illustrated more grandly, more simply, and with yet profounder meanings.

Spain falls, not as Carlyle imagines, because it "rejects the Faith proffered by the visiting angel"—a Protestant Spain is impossible—but because Spain seeks to stifle in the Netherlands, in Europe at large, that freedom which modern Europe had come to regard as dearer than life—freedom to worship God after the manner nearest to its heart. But disaster taught Spain nothing—

Alas, for mortal history! In happy fortune

A shadow might overturn its height; whilst of disaster

A wet sponge at a stroke effaces the lesson;

And 'tis this last I deem life's greater woe.

The embittered wisdom of Aeschylus finds in all history no more shining comment than the decline of Spain.[4]

The gloomy resolution of the Austrian Ferdinand II, the internecine war of thirty years which he provokes, sullenly pursues, and in dying bequeaths to his son, are visited upon his house at Leuthen, Marengo, Austerlitz, and in the overthrow of the empire devised ten centuries before by Leo III and Charlemagne.

And with the Revocation, with Le Tellier and the Bull Unigenitus, the procession of the French kings begins, which ends in the Place de la Révolution:—"Son of St. Louis, ascend to Heaven."

From this thraldom to the past, to the ideal of Rome, Imperial Britain, first amongst modern empires, completely breaks. For it is a new empire which Imperial Britain presents to our scrutiny, a new empire moulded by a new ideal.

Let me illustrate this by a contrast—a contrast between two armies and what each brings to the vanquished.

Who that has read the historian of Alva can forget the march of his army through the summer months some three hundred and thirty years ago? That army, the most perfect that any captain had led since the Roman legions left the world, defies from the gorges of Savoy, and division behind division advances through the passes and across the plains of Burgundy and Lorraine. One simile leaps to the pen of every historian who narrates that march, the approach of some vast serpent, the glancing of its coils unwinding still visible through the June foliage, fateful, stealthy, casting upon its victim the torpor of its irresistible strength. And to the Netherlands what does that army bring? Death comes with it—death in the shape most calculated to break the resolution of the most dauntless—the rack, the solitary dungeon, the awful apparel of the Inquisition torture-chamber, the auto-da-fé, and upon the evening air that odour of the burning flesh of men wherewith Philip of Spain hallowed his second bridals. These things accompany the march of Alva. And that army of ours which day by day advances not less irresistibly across the veldt of Africa, what does that army portend? That army brings with it not the rack, nor the dungeon, nor the dread auto-da-fé; it brings with it, and not to one people only but to the vast complexity of peoples within her bounds, the assurance of England's unbroken might, of her devotion to that ideal which has exercised a conscious sway over the minds of three generations of her sons, and quickened in the blood of the unreckoned generations of the past—an ideal, shall I say, akin to that of the prophet of the French Revolution, Diderot, "élargissez Dieu!"—to liberate God within men's hearts, so that man's life shall be free, of itself and in itself, to set towards the lodestar of its being, harmony with the Divine. And it brings to the peoples of Africa, to whom the coming of this army is for good or evil so eventful, so fraught with consequences to the future ages of their race, some assurance from the designs, the purposes which this island has in early or recent times pursued, that the same or yet loftier purposes shall guide us still; whilst to the nations whose eyes are fastened upon that army it offers some cause for gratulation or relief, that in this problem, whose vast issues, vista receding behind vista, men so wide apart as Napoleon I. and Victor Hugo pondered spell-bound; that in this arena where conflicts await us beside which, in renunciation, triumph, or despair, this of to-day seems but a toy; that in this crisis, a crisis in which the whole earth is concerned, the Empire has intervened, definitely and for all time, which more than any other known to history represents humanity, and in its dealings with race distinctions and religious distinctions does more than any other represent the principle that "God has made of one blood all the nations of the earth."

In these two armies then, and in what each brings to the vanquished, the contrast between two forms of Imperialism outlines itself sharply. The earlier, that of the ancient world, little modified by mediaeval experiments, limits itself to concrete, to external justice, imparted to subject peoples from above, from some beneficent monarch or tyrant; the later, the Imperialism of the modern world, the Imperialism of Britain, has for its end the larger freedom, the higher justice whose root is in the soul not of the ruler but of the race. The former nowhere looks beyond justice; this sees in justice but a means to an end. It aims through freedom to secure that men shall find justice, not as a gift from Britain, but as they find the air around them, a natural presence. Justice so conceived is not an end in itself, but a condition of man's being. In the ancient world, government ever tends to identify itself with the State, even when, as in Rome or Persia, that State is imperial. In the modern, government with concrete justice, civic freedom as its aims, ever tends to become but a function of the State whose ideal is higher.

The vision of the De Monarchia—one God, one law, one creed, one emperor, semi-divine, far-off, immaculate, guiding the round world in justice, the crowning expression of Rome's ideal by a great poet whose imagination was on fire with the memory of Rome's grandeur—does but describe after all an exterior justice, a justice showered down upon men by a beneficent tyrant, a Frederick I, inspired by the sagas of Siegfried and of Charlemagne, or the second Frederick, the "Wonder of the World" to the thirteenth century, and ever alluring, yet ever eluding, the curiosity of the nineteenth; or a Henry VII, ineffectual and melancholic. Such "justice" passes easily by its own excess into the injustice which dispatches Alva's army or finds bizarre expression in the phrase of "le Roi soleil,"—"The State? I am the State." The ideal of modern life, the ideal of which Britain is the supreme representative amongst existing empires, starting not from justice but from freedom, may be traced beyond the French Revolution and the Reformation, back even to the command "Render unto Caesar." That word thrust itself like a wedge into the ancient unity of the State and God. It carried with it not merely the doom of the Roman Empire, but of the whole fabric of the ancient relations of State and Individual. Yet Sophocles felt the injustice of this justice four centuries before, as strongly as Tertullian, the Marat of dying Rome, felt it two centuries after that command was uttered.

Such then is the character of the ideal. And in the resolution as a people, for the furtherance of its great ends, to do all, to suffer all, as Rome resolved, lies what may be described as the destiny of Imperial Britain. None more impressive, none loftier has ever arisen within the consciousness of a people. And to England through all her territories and seas the moment for that resolution is now. If ever there came to any city, race, or nation, clear and high through the twilight spaces, across the abysses where the stars wander, the call of its fate, it is NOW! There is an Arab fable of the white steed of Destiny, with the thunder mane and the hoofs of lightning, that to every man, as to every people, comes once. Glory to that man, to that race, who dares to mount it! And that steed, is it not nearing England now? Hark! the ringing of its hoofs is borne to our ears on the blast!

Temptations to fly from this decision, to shrink from the great resolve, to temporize, to waver, have at such moments ever presented themselves to men and to nations. Even now they present themselves, manifold, subtly disguised, insidiously persuasive, as exhortations to humility, for instance, as appeals to the deference due to the opinion of other States. But in the faith, the undying faith, that it, and it alone, can perform the fate-appointed task, dwells the virtue of every imperial race that History knows. How shall any empire, any state, conscious of its destiny, imitate the self-effacement prescribed to the individual—"In honour preferring one another"? This in an imperial State were the premonition of decay, the presage of death.

But there is one great pledge, a solemn warrant of her resolve to swerve not, to blench not, which England has already offered. That pledge is Elandslaagte, it is Enslin, the Modder, and the bloody agony of Magersfontein. For it grows ever clearer as month succeeds month that it is by the invincible force of this ideal, this of Imperial Britain, that we have waged this war and fought these battles in South Africa. If it be not for this cause, it is for a cause so false to all the past, from Agincourt to Balaklava, that it has but to be named to carry with it its own refutation. There is a kind of tragic elevation in the very horror of the march of Attila, of Ginghis Khan, or of Timour. But to assemble a host from all the quarters of this wide Empire, to make Africa, as it were, the rendezvous of the earth, for the sake of a few gold, a few diamond mines, what language can equal a design thus base, ambition thus sordid? And if we call to memory the dead who have fallen in this war, those who at its beginning were with us in the radiance of their manhood, but now, still in the grave, all traces of life's majesty not yet gone from their brow, and if those dead lips ask us, "Why are we thus? And in what cause have we died?" were it not a hard thing for Britain, for Europe, indeed for all the world, if the only answer we could make to the question should be, "It is for the mines, it is for the mines!" No man can believe that; no man, save him whose soul faction has sealed in impenetrable night! The imagination recoils revolted, terror-struck. Great enterprises have ever attracted some base adherents, and these by their very presence seem to sully every achievement recorded of nations or cities. But to arraign the fountain and the end of the high action because of this baser alloy? To impeach on this account all the valour, all the wisdom long approved? Reply is impossible; the thing simply is not British.

Indeed, in very deed, it is for another cause, and for another ideal—an ideal that, gathering to itself down the ages the ardour of their battle-cries, falls in all the splendour of a new hope about the path of England now. For this these men have died, from the first battle of the war to that fought yesterday. And it is this knowledge, this certainty, which gives us heart to acquiesce, as each of us is compelled to acquiesce, in the presence of that army in South Africa. They have fallen, fighting for all that has made our race great in the past, for this, the mandate of destiny to our race in the future. They have fallen, those youths, self-devoted to death, with a courage so impetuous, casting their youth away as if it were a thing of no account, a careless trifle, life and all its promises! But yesterday in the flush of strength and beauty; to-night the winds from tropic seas stir the grass above their graves, the southern stars look down upon the place of their rest. For this ideal they have died—"in their youth," to borrow the phrase of a Greek orator, "torn from us like the spring from the year."

Fallen in this cause, in battle for this ideal, behold them advance to greet the great dead who fell in the old wars! See, through the mists of time, Valhalla, its towers and battlements, uplift themselves, and from their places the phantoms of the mighty heroes of all ages rise to greet these English youths who enter smiling, the blood yet trickling from their wounds! Behold, Achilles turns, unbending from his deep disdain; Rustum, Timoleon, Hannibal, and those of later days who fell at Brunanburh, Senlac, and Trafalgar, turn to welcome the dead whom we have sent thither as the avant-garde of our faith, that in this cause is our destiny in this the mandate of our fate.

[1] The Latin work of Osorius, De rebus gestis Emmanuelis regis Lusitaniae, appeared in 1574, two years later than Os Lusiadas. The twelve books of Osorius cover the twenty-six years between 1495 and 1521, thus traversing parts of the same ground as Camoens. But the hero of Osorius is Alboquerque. His affectation of Ciceronianism, the literary vice of the age, casts a suspicion upon the sincerity of many of his epithets and paragraphs, yet the work as a whole is composed with his eyes upon his subject. Seven years after the Latin, a French translation, a beautifully printed folio from Estienne's press, was published, containing eight additional books, by Lopez de Castanedo and others, bringing the history down to 1529.

[2] The first of Pitt's two remarkable speeches in the great debate of

April, 1792, on the Abolition of the Slave-trade was made on April and

Pitt, according to a pamphlet report printed by Phillips immediately

afterwards, rose after an all-night sitting to speak at four o'clock on

Tuesday morning (April 3rd). The close of the speech is thus reported:

"If we listen to the voice of reason and duty, and pursue this night

the line of conduct which they prescribe, some of us may live to see a

reverse of that picture, from which we now turn our eyes with pain and

regret. We may live to behold the natives of Africa engaged in the

calm occupations of industry, in the pursuits of a just and legitimate

commerce. We may behold the beams of science and philosophy breaking

in upon their land, which at some happy period in still later times may

blaze with full lustre, and joining their influence to that of pure

religion, may illumine and invigorate the most distant extremities of

that immense continent. Then may we hope that even Africa, though last

of all the quarters of the globe, shall enjoy at length, in the evening

of her days, those blessings which have descended so plentifully upon

us in a much earlier period of the world. Then also will Europe,

participating in her improvements and prosperity, receive an ample

recompense for the tardy kindness (if kindness it can be called) of no

longer hindering that continent from extricating herself out of the

darkness which in other more fortunate regions has been so much more

speedily dispelled—

Non primus equis oriens afflavit anhelis,

illic sera rubens accendit lumina Vesper.

Then, Sir, may be applied to Africa those words, originally indeed used

with a different view—

His demum exactis—

devenere locos laetos, et amoena vireta

fortunatorum nemorum, sedesque beatas;

largior hie campos aether, et lumine vestit

purpureo."

Pitt's second speech, of which only a brief impassioned fragment remains, was delivered on April 27th (Parl. Hist. xxix, pp. 1134-88).

[3] Justinian not only in his policy but in his laws sums the history of the three preceding centuries, and determines the history of the centuries which follow. To Dante he represents at once the subtleties of Jurisprudence and Theology. The Eagle's hymn in the Paradiso (Cantos xix, xx) defines the limitations and the glory of Roman and Mediaeval Imperialism. The essence of the entire treatise De Monarchia is in these cantos; and Canto vi, where Justinian in person speaks, is informed by the same spirit.

[4] Portugal in the first half of the sixteenth century presents a further instance of an empire actuated by the same ideals as those of Spain. Within a single century, almost within the memory of a single life, Portugal appears successively as a strong united nation, an empire of great and far-stretched renown, and then, by a revolution in fortune of which there are few examples, as a vanquished and subject State. Her merchants were princes, her monarchs, John II, Emmanuel, John III, and Sebastian, were in riches kings of the kings of Europe. But during the brief period of Portugal's glory, tyranny and bigotry went hand in hand. To the pride of her conquistadores was added the fanaticism of Xavier and his retinue, and in the very years when within the same region Baber and Akbar were raising the wise and tolerant administration of the first Moguls, the Inquisition, with its priests, incantations, and torture-chambers, was established at Goa. The resemblance in feature, bearing, and in character between the Gilberts, the Grenvilles, and the Alboquerques and Almeidas is indisputable; but certain ineffaceable and intrinsic distinctions ultimately force themselves upon the mind. And these distinctions mark the divergence between the fate and the designs of England and the fate and the designs of Lusitania, between the empire of Portugal and that of Britain. Indeed, upon the spirit of mediaeval imperialism the work of Osorius is hardly less illuminating than the deliberate treatise of Dante.

Man's path lies between the living and the dead, and History seems to move between two hemispheres that everywhere touch yet unite nowhere, the Past, shadowy, vast, illimitable, that at each moment ends, the Future not less shadowy, vast, illimitable, that at each moment begins. The question, "What is History?" is but the question, "What is Life?" transferred from the domain of the Present to the domain of the Past. To understand the whorl of a shell would require an intelligence that has grasped the universe, and for the knowledge of the history of an hour the aeons of the fathomless past were not excessive as a preliminary study. Massillon's injunction, "Look thou within," does but discover to our view in nerve-centres, in emotional or in instinctive tendencies, hieroglyphics graven by long vanished ancestral generations. But Nature, to guard man from despair, has fashioned him a contemporary of the remotest ages. The beam of light, however far into space it travel, yet remains unsevered from the orb whence it sprang, and Man, the youngest-born of Time, is yet one with the source whence he came. As age flies past after age, the immanence of the Divine grows more, not less insistent. Each moment indeed is rooted in the dateless past inextricably; but to its interpretation the soul comes, a wanderer from aeons not less distant, laden with the presaging memories, experiences, innumerable auxiliaries unseen, which the past itself has supplied for its own conquest or that of the present. Trusting to these, man is unmoved at the narrowness of his conscious sovereignty, as the eye is unmoved at the narrow bounds that hedge its vision, and finds peace where he would otherwise have found but despair.

Those affinities, those intimate relations of the past and present, are the basis of speculative politics. A judgment upon a movement in the present, an opinion hazarded upon the curve which a state, a nation, or an empire will describe in the future, is of little value unless from a wide enough survey the clear sanction of the past can be alleged in its support.

Assuming therefore that in the ideal delineated above we have the ideal of a race destined to Empire, and at last across the centuries grown conscious of that destiny, the question confronts us—is it possible out of the past, not surveying it from the vantage-ground of the present merely, but as it were living into the present from the past, to foreshadow the rise of this consciousness? Or turning back in the light of this consciousness to the past, is there offered by the past a justification of this interpretation of the present, of this movement styled "Imperialism"?

The heart of the matter lies in the transformation of mediaeval patriotism into modern imperialism, in the evolution or development which out of the Englishman of the earlier centuries has produced the Englishman of the present, moved by other and higher political ends. Is there any incident or series of incidents in our history, of magnitude enough profoundly to affect the national consciousness, to which we may look for the causes, or for the formative spirit, of this change? And in their effect upon the national consciousness of Britain have these incidents followed any law traceable in other nations or empires?

There is a kind of criticism directed against politics which, year by year or month by month, makes the discovery that between the code which regulates the action of States and the code which regulates the actions of individuals divergencies or contradictions are constantly arising. War violates the ordinances of religion; diplomacy, the ordinances of truth; expediency, those of justice. And the conclusion is drawn that whatever be the softening influences of civilization upon the relations of private life, within the sphere of politics, barbarism, brutally aggressive or craftily obsequious, reigns undisturbed. Era succeeds era, faiths rise and set, statesmen and thinkers, prophets and martyrs, act, speak, suffer, die, and are seen no more; but, scornful of all their strivings, the great Anarch still stands sullen and unaltered by the centuries. And these critics, undeterred by Burke's hesitation to "draw up an indictment against a whole nation," make bold to arraign Humanity itself, charging alike the present and the past with perpetual self-contradiction, an hypocrisy that never dies.

Underlying this impeachment of Nations and States in their relations to each other the assumption at once reveals itself, that every State, whether civic, national, or imperial, is but an aggregate of the individuals that compose it, and should accordingly be regulated in its actions by the same laws, the same principles of conduct, as control the actions of individuals. And he therefore is the greatest statesman who constrains the State as nearly as possible into the line prescribed to the individual—whatever ruin and disaster attend the rash adventure! The perplexity is old as the embassy of Carneades, young as the self-communings of Mazzini.

Yet certain terms, current enough amongst those who deliver or at least acquiesce in this indictment (such as "Organism" or "Organic Unity" as applied to the State), might of themselves suggest a reconsideration of the axiom that the State is but an aggregate of individuals. The unity of an organism, though arising from the constituent parts, is yet distinct from the unity of those parts. Even in chemistry the laws which regulate the molecule are not the laws which regulate the constituent atoms. And in that highest and most complex of all unities, the State, we find, as we might expect to find, laws of another range, and a remoter purport, obscurer to us in their origins, more mysterious in their tendencies, than the laws which meet us in the unities which compose it. In the region in which States act and interact, whether with Plato we regard it as more divine, or as Rousseau passionately insists, as lower, the laws which are valid must at least be other than the laws valid amongst individuals. The orbit described by the life of the State is of a wider, a mightier sweep than the orbit of the separate life. The life which the individual surrenders to the State is not one with the life which he receives in return; yet even of this interchange no analysis has yet laid bare the conditions.

These considerations are not designed to imply that in the relations between States the code of individual ethics is necessarily annulled; but to suggest that the laws which regulate the actions or the suffering of States, as such, have too peremptorily been assumed to be, by nature and the ground-plan of the universe, identical with the laws of individual life, its actions or its sufferings, and that it is something of a petitio principii, in the present stage of our knowledge, to judge the one by the standards applicable only to the other.

The profoundest students of the actions of States have in all times been aware, not of the fixed antagonism, but of the essential distinction, between the two codes. Every principle of Machiavelli is implicit in Thucydides, and Sulla, whom Montesquieu selects as the supreme type of Roman grandeur, does but follow principles which reappear in the politics of an Innocent III or a Richelieu, a Cromwell or an Oxenstiern.[1] The loss of Sulla's Commentaries[2] is irreparable as the loss of the fifth book of the Annals of Tacitus or the burnt Memoirs of Shaftesbury; in the literature of politics it is a disaster without a parallel. What Sulla felt as a first, most living impulse appears in later times as a colder, a critical judgment. It is thus that it presents itself to Machiavelli, not the writer of that jeu d'esprit, Il Principe, perplexing as Hamlet, and as variously interpreted, but the author of the stately periods of the Istorie and the Discorsi, the haughtiest of speculators, and in politics the profoundest of modern thinkers. M. Sorel encounters little difficulty in proving that the diplomacy of Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is but an exposition of the principles of the Discorsi; Frederick the Great, who started his literary activity by the refutation of the Prince, began and ended his political career as if his one aim were to illustrate the maxims that in the rashness of inexperience he had condemned; and within living memory, the vindicator of Oliver Cromwell found in the composition of the same Frederick's history the solace and the torment of his last and greatest years.

To press this inquiry further would be foreign to the present subject; enough has been said to indicate that from whatever deep unity they may spring, the laws which determine the life of a State, as displayed in History, are not identical with the laws of individual life. The region of Art, however, seems to offer a neutral territory, where it is possible to obtain some perception, or Ahnung as a German would say, of the operation in the life of States of a law which bears directly upon the problem before us.

In the history of past empires, their rise and decline, in the history of this Empire of Britain from the coming of Cerdic and Cynric to the present momentous crisis, there reveals itself a force, an influence, not without analogy to the influence ascribed by Aristotle to Attic Tragedy. The function of Tragedy he defined as the purification of the soul by Compassion and by Terror—+di eléou kaì phóbou kátharsis+.[3] Critics and commentators still debate the precise meaning of the definition; but my interpretation, or application of it to the present inquiry is this, that by compassion and terror the soul is exalted above compassion and terror, is lifted above the touch of pity or of fear, attaining to a state like that portrayed by Dante—

Io son fatta da Dio, sua merce, tale,

Che la vostra miseria non mi tange

Ne fiamma d' esto incendio non m' assale.[4]

In the tragic hour the soul is thus vouchsafed a deeper vision, discerns a remoter, serener, mightier ideal which henceforth it pursues unalterably, undeviatingly, as if swept on by a law of Nature itself. Sorrow, thus conceived, is the divinest thought within the Divine mind, and when manifested in that most complex of unities, the consciousness of a State, the soul of a race, it assumes proportions that by their very vagueness inspire but a deeper awe, presenting a study the loftiest that can engage the human intellect.

Genius for empire in a race supplies that impressiveness with which a heroic or royal origin invests the protagonist of a tragedy, an Agamemnon or a Theseus. Hence, though traceable in all, the operation of this law, analogous to the law of Tragedy, displays itself in the history of imperial cities or nations in grander and more imposing dimensions. Nowhere, for instance, are its effects exhibited in a more impressive manner than in the fall of Imperial Athens—most poignantly perhaps in that hour of her history which transforms the character of Athenian politics, when amid the happy tumult of the autumn vintage, the choric song, the procession, the revel of the Oschophoria, there came a rumour of the disaster at Syracuse, which, swiftly silenced, started to life again, a wild surmise, then panic, and the dread certainty of ruin. That hour was but the essential agony of a soul-conflict which, affecting a generation, marks the transformation of the Athens of Kimon and Ephialtes, of Kleon and Kritias, into the Athens[5] of Plato and Isocrates, of Demosthenes and Phocion. In the writings of such men, in their speculations upon politics, one pervading desire encounters us, alike in the grave serenity of the Laws, the impassioned vehemence of the Crown, in the measured cadences of the Panegyric, the effort to lead Athens towards some higher enterprise, to secure for Athens and for Hellas some uniting power, civic or imperial, another empire than that which fell in Sicily, and moved by a loftier ideal. The serious admiration of Thucydides for Sparta, the ironic admiration of Socrates, Plato's appeals to Crete and to ancient Lacedsemon, these are not renegadism, not disloyalty to Athens, but fidelity to another Athens than that of Kleon or of Kritias. History never again beheld such a band of pamphleteers![6]

In the history of Rome, during the second war against Carthage, a similar moment occurs. After Cannae, Rome lies faint from haemorrhage, but rises a new city. The Rome of Gracchus and of Drusus is greater than the Rome of the Decemvirs. It is not the inevitable change which centuries bring; another, a higher purpose has implanted itself within Rome's life as a State. The Rome of Gracchus and of Drusus announces Imperial Rome, the Rome of the Caesars.

So in the history of Islam, from the anguish and struggles of the eighth century, the Islam of Haroun and Mutasim arises, imparting even to dying Persia, as it were, a second prime, by the wisdom and imaginative justice of its sway.

In the development of Imperial Britain, the conflict which in the life-history of these two States, Athens and Rome, has its essential agony at Cannae or at Syracuse, the conflict which affects the national consciousness as the hour of tragic insight affects the individual life, finds its parallel in the fifteenth century. After the short-lived glory of Agincourt and the vain coronation at Paris, humiliation follows humiliation, calamity follows calamity. The empire purchased by the war of a century is lost in a day; and England's chivalry, as if stung to madness by the magnitude of the disaster, turns its mutilating swords, like Paris after Sedan, against itself. The havoc of civil war prolongs the rancour and the shame of foreign defeat, so that Rheims, Chatillon, Wakefield, Barnet, and Tewkesbury, with other less remembered woes, seem like moments in one long tempest of fiery misery that breaks over England, stilled at last in the desperate lists at Bosworth.

This period neglected, perhaps wisely neglected, by the political historian, is yet the period to which we must turn for the secret sources of that revolution in its political character which, furthered by the incidents that fortune reserved for her, has gradually fashioned out of the England of the Angevins the Imperial Britain of to-day.

In England it is possible to trace the operation of this transforming power, which I have compared to the transforming power of tragedy, in a very complete manner. It reveals itself, for instance, in two different modes or aspects, which, for the sake of clearness, may be dealt with separately. In the first of these aspects, deeply and permanently affecting the national consciousness, which as we have seen is distinct from the sum of the units composing it, the law of tragedy appears as the influence of suffering, of "terror" in the mystic transcendental sense of the word, of reverent fear, yet with it, serene and dauntless courage. This influence now makes itself felt in English politics, in English religion, in English civic life.

If we consider the history of England prior to this epoch, it might at first sight appear as if here were a race emphatically not destined for empire. Not in her dealings with conquered France, not in Ireland, not in Scotland, does England betray, in her national consciousness, any sympathy even with that aspiration towards concrete justice which marks the imperial character of Persia and of Rome. England seems fated to add but one record more to the tedious story of unintelligent tyrant States, illustrating the theme—+húbris phyteúei tyrannón+—"insolence begets the tyrant!" Even to her contemporary, Venice, the mind turns from England with relief; whilst in the government of Khorassan by the earlier Abbassides we encounter an administration singularly free from the defects that vitiate Imperial Rome at its zenith. And now in the days of the first Tudors all England's efforts at empire have come to nothing. Knut's empire sinks with him; Norman and Plantagenet follow; but of their imperial policy the dying words of Mary Tudor, "Calais will be found graven on my heart," form the epitaph. It was not merely the loss of Calais that oppressed the dying Queen, but she felt instinctively, obscurely, prophetically that here was an end to the empire which her house had inherited from Norman and Plantagenet.

But in the national consciousness, the consciousness of the State, a change is now apparent. As Athens rose from Syracuse, a new Athens, as Rome rose from Cannae, a new city, to conquer by being conquered, so from the lost dreams of empire over France, over Scotland, England arises a new nation. This declares itself in the altered course of her policy alike in France, Ireland, and Scotland. In Ireland, for instance, an incomplete yet serious and high-purposed effort is made to bring, if not justice, at least law to the hapless populations beyond the Pale. Henry VIII again, like Edward I, is a masterful king. In politics, in constructive genius, he even surpasses Edward I. He abandons the folly of an empire in France, and though against Scotland he achieves a triumph signal as that of Edward, he has no thought of reverting to the Plantagenet policy. He defeats the Scots at Flodden; but he has the power of seeing that in spite of his victory they are not defeated at all. King James IV lies dead there, with all his earls around him, like a Berserker warrior, his chiefs slain around him, "companions," comites indeed, in that title's original meaning. But the spirit of the nation is quickened, not broken, and Henry VIII, recognising this, steadily pursues the policy which leads to 1603, when these two peoples, by a mutual renunciation, both schooled in misery, and with the Hebrew phrase, "Well versed in suffering, and in sorrow deeply skilled," working so to speak in their very blood, are united. The Puritan wars, and the struggle for an ideal higher than that of nationality, cement the union.

In the development of the life of a State, the distance in time between causes and their visible effects often makes the sequence obscure or sink from sight altogether. As in geology the century is useless as a unit to measure the periods with which that science deals, and as in astronomy the mile is useless as a standard for the interstellar spaces; so in history, in tracing the organic changes within the conscious life of a State, the lustrum, the dekaetis, or even the generation, would sometimes be a less misleading unit than the year. The England of Elizabeth drew the first outline of the Empire of the future; but five generations were to pass before the Britain of Chatham[7] could apply itself with a single-hearted resolution to fill that outline in, and yet three other generations before this people as a whole was to become completely conscious of its high destiny. Freedom of religion and constitutional liberty had to be placed beyond the peril of encroachment or overthrow, before the imperial enterprise could be unreservedly pursued; but the deferment of the task has nerved rather than weakened the energy of her resolve. Had England fallen in the Maryborough wars, she would have left a name hardly more memorable than that of Venice or Carthage, illustrious indeed, but without a claim to original or creative Imperialism. But if she were to perish now, it would be in the pursuance of a design which has no example in the recorded annals of man.

Similarly in Rome, two centuries sever the Rome which rose from Cannae from the Rome which administered Egypt and Hispania. And in Islam four generations languish in misery before the true policy of the Abbassides displays itself, striking into the path which it never abandoned.

In England then the influence of this epoch of tragic insight, and of its transforming force, advances imperceptibly, unnoted across two generations, yet the true sequence of cause and effect is unquestionable. The England which, towards the close of the eighteenth century, presents itself like a fate amongst the peoples of India, bears within itself the wisdom which in the long run will save it from the errors, and turn it from the path, which the England of the Plantagenets followed in Ireland and in France. The national consciousness of England, stirred to its depths by its own suffering, its own defeats, its own humiliations, comes there in India within the influence of that which in the life of a State, however little it may affect the individual life as such, is the deepest of all suffering. England stands then in the presence of a race whose life is in the memories of its past; its literature, its arts, its empires that rise and dissolve like dreams; its religions, its faiths, with all their strange analogies, dim suggestions, mysterious as a sea cavern full of sounds. Hard upon this experience in India comes that of the farther East, comes that of Egypt, that of Africa in the nineteenth century. How can such a fortune fail to change the heart, the consciousness of a race, imparting to it forces from these wider horizons, deepening its own life by the contact with this manifold environment? He who might have been a de Montfort, a Grenville, or a Raleigh, is now by these presences uplifted to other ideals, and by these varied and complex influences of suffering, and the presence of suffering, raised from the sphere of concrete freedom and concrete justice to the higher realm ruled by imaginative freedom, imaginative justice, which Sophocles, in the choral ode of the Oedipus, delineates, "the laws of sublimer range, whose home is the pure ether, whose origin is God alone."

The second mode or aspect in which the Law of Tragedy as applied to history reveals itself in the life of a State, corresponds to the moment of intenser vision in the individual life, when the soul, exalted by "compassion and terror," discerns the deeper truth, the serener ideal which henceforth it pursues as if impelled by the fixed law of its being. There is a word coined by Aristotle which comes down the ages to us, bringing with it as it were the sound of the griding of the Spartan swords as they leapt from their scabbards on the morning of Thermopylae, the +enérgeia tês psychês+—the energy of the soul. This energy of the soul in Aristotle is the vertù of Machiavelli, the spring of political wisdom, the foundation of the greatness of a State. It is the immortal energy which arises within the consciousness of a nation, or in the soul of an individual, as the result of that hour of insight, of pity, of anguish, or contrition. It is the heroism which adverse fortune greatens, which antagonism but excites to yet sublimer daring.

In Rome this displays itself, both in policy and in war, in the centuries that immediately succeed Cannae. Nothing in history is more worthy of attention than the impression which Rome in this epoch of her history made upon the minds of men, above all, upon the mind of Hellas. Its expression in Polybius is remarkable.

Polybius, if not one of the greatest of thinkers on politics, has a place with the greatest political historians for all time. It was his work which Chatham placed in the hands of his son, the younger Pitt, as the supreme guide in political history. Polybius has every inducement to abhor Rome, to judge her actions with jealous and unfriendly eyes. His father was the companion of Philopoemen, the heroic leader of the Achaean league, sometimes styled "the last of the Greeks," the Kosciusko of the old world. Polybius himself is a hostage in Rome, the representative of a defeated race, a lost cause; and yet after years of study of his conquerors, possessing every means for a just estimate of their actions and motives in the senate, on the battlefield, in the intimacies of private life, the conviction of his heart becomes that there in Rome is a people divinely appointed to the government, not of Hellas merely, but of the whole earth. The message of his history, composed with scrupulous care, and a critical method rare in that age, is that the very stars in their courses fight for Rome, whether she wages war against Greek or against Barbarian, that hers is the domination of the earth, the empire of the world, and it is to the eternal honour of Greece that it accepted this message. The Romano-Hellenic empire is born. Other men arise both to the east and to the west of the Adriatic, in whom the Greek and Roman genius are fused, who pursue the ideal and amplify or adorn the thought which Polybius was the first to express immortally. It inspires the rhetoric of Cicero; and falls with a kind of glory on the verse of Virgil—

Excudent alii spirantia mollius aera,

credo equidem, vivos ducent de marmore vultus,

orabunt causas melius, caelique meatus

describent radio et surgentia sidera dicent:

tu regere imperio populos Romane memento;

hae tibi erunt artes; pacisque imponere morem,

parcere subjectis et debellare superbos.

The tutor of Hadrian makes it the informing idea of his parallel "Lives," and gives form and feature to a grandeur that else were incredible. It appears in the duller work of the industrious Dion Cassius, and in the fourth century forges some of the noblest verse of Claudian. And as we have seen, it is enshrined nine centuries after Claudian in the splendid eloquence of the De Monarchia, and yields such spent, such senile life as they possess, to the empires of Hapsburg and Bourbon. Thus this divine energy, which after Cannae uplifts Rome, riveting the sympathies of Polybius, outlives Rome itself, still controlling the imaginations of men, until its last flicker in the eighteenth century.

Where in the history of England, in the life of England as a State, does this energy, exalted by the hour of tragic vision, manifest itself? Recollect our problem; it is by analysis, comparison, and contrast, to discover what is the testimony of the past to Britain's title-deeds of empire.

Great races, like great individuals, resemble the giants in the old myth, the gigantes, the earth-born, sons of Gaia, who, thrown in the wrestle, touched her bosom, and rose stronger than before defeat. England stood this test in the sixteenth century, rising from that long humiliating war with France, that not less humiliating war with Scotland, greater than before her defeat. This energy of the soul, quickened by tragic insight, displays itself not merely in the Armada struggle but before that struggle, under various forms in pre-Armada England.

The spirit of the sea-wolves of early times, of the sailors who in the fourteenth century fought at Sluys, and made the Levant an English lake, lives again in the Tudor mariners. But it has been transformed, and sets towards other and greater endeavours, planning a mightier enterprise. These adventurers make it plain that on the high seas is the path of England's peace; that the old policy of the Plantagenet kings, with all its heroism and indisputable greatness, had been a false policy; that England's empire was not to be sought on the plains of France; that Gilbert, Drake, Raleigh, and Frobisher have found the way to the empire which the Plantagenets blindly groped after.

As Camoens in Portugal invents a noble utterance for the genius of his nation, for the times of Vasco da Gama and of Emmanuel the Great, so this spirit of pre-Armada England, of England which as yet has but the memory of battles gained and lost wars, finds triumphant expression in Marlowe and his elder contemporaries. Marlowe's[8] great dialect seems to fall naturally from the lips of the heroes of Hakluyt's Voyages, that work which still impresses the imagination like the fragments of some rude but mighty epic, and in their company the exaggeration, the emphasis of Tamburlaine are hardly perceptible. In Martin Frobisher, for instance, how the purpose which determines his career illumines for us the England of the first years of Elizabeth! Frobisher in early manhood torments his heart with the resentful reflection, "What a blockish thing it has been on the part of England to permit the Genovese Columbus to discover America!" That task was clearly England's! "And now there being nothing great left to be done," the sole work Frobisher finds worth attempting is the discovery of the northwest passage to Cathay. Upon this he spends the pith of his manhood year by year, and the result of all the labours of this sea-Hercules, well! it is perhaps to be sought in those dim beings, "half-man, half-fish," whom he brings back from some voyage, those forlorn Esquimaux who, seen in London streets, and long remembered, suggested to the dreaming soul of Shakespeare Caliban and his island. Frobisher's watchword on the high seas is memorable. In the northern latitudes, under the spectral stars, the sentinel of the Michael gives the challenge "For God the Lord," and sentinel replies, "And Christ His Sonne."

The repulse of Spain is but the culminating achievement of this energy of the soul which greatens the life of England already in pre-Armada times. And simultaneously with the conflict against Spain this same energy attests its presence in a form assuredly not less divine within the souls of those who rear that unseen empire, whose foundations are laid eternally in the thoughts of men, the empire reared by Shakespeare, Webster, Beaumont, and Milton.

In the seventeenth century it inspires the statesmen of England not only with the ardour for constitutional freedom, but engages them in ceaseless and not unavailing efforts towards a deeper conception of justice and of liberty, foreshadowing unconsciously the ideals of later times. If the Thirty Years' War did nothing else for England it implanted in her great statesmen a profound distrust of the imperial systems of the Bourbons and the Hapsburgs. Eliot, for instance, in the work entitled The Monarchy of Man, lofty in its form as in its thought, written in his prison, though studying Plato and the older ideals of empire, is yet obscurely searching after a new ideal. We encounter a similar effort in the great Montrose, capable of that Scottish campaign, and of writing one of the finest love-songs in the language, capable also of some very vivid thoughts on statesmanship. In natures like Eliot and Montrose, the height of the ideal determines the steadfastness of the action. And that ideal, I repeat, is distinct from Plato's, distinct from Dante's, and from that of the Bourbon and Hapsburg empires, in which Dante's conception is but rudely or imperfectly developed. The ideal of these English statesmen is framed upon another conception of justice, another conception of freedom, equally sublime, and more catholic and humane. Whatever its immediate influence upon certain of their contemporaries, over their own hearts it was all-powerful. The very vividness with which they conceive the ideal, and the noble constancy with which they pursue it, link the high purposes of these two men to the purposes of Milton, of Cromwell, of Selden, and of Falkland. The perfect State, the scope of its laws, government, religion, to each is manifest, though the path that leads thither may seem now through Monarchy, now through a Republic, or at other times indistinct, or lost altogether in the bewildering maze of adverse interests. From the remote nature of their quest arises much of the apparent inconsistency in the political life of that era. The parting of Pym and Strafford acquires an added, a tragic poignancy from the consciousness in the heart of each that the star which leads him on is the star of England's destiny.

Hence, too, the suspicion attached to men like Selden and Falkland of being mere theoricians in advance of their time,—an accusation fatal to statesmanship. But the advent of that age was marked by so much that was novel in religion,[9] in State, in foreign and domestic policy, the new direction of imperial enterprise, the unity of two nations, ancient and apparently irreconcilable foes, the jarring creeds, convulsing the life of both these nations, for both were deeply religious, that it were rash to accuse of rashness any actor in those times. But it is the adventurous daring of their spirits, the swift glance searching the horizons of the future, it is that very energy of the soul of which I have spoken which render these statesmen obnoxious to the suspicion of theory. The temper of Selden, indeed, in harmony with the thoughtful and melancholy cast of his features, disposed him to subtlety and niceness of argument, and with a division pending, often deprived his words of a force which homelier orators could command. And yet his career is a presage of the future. Toleration in religion, freedom of the press, the supremacy of the seas, the habeas corpus, are all lines along which his thought moves, not so much distancing as leading the practical statesmen of his generation. And there is a curious fitness in the dedication to him in 1649 of Edward Pococke's Arabic studies, which nearly a century and a half later were to form the basis of Gibbon's great chapters. But the year of Mare Clausum is at once the greatest in Selden's life, and the last months of greatness in the life of his royal master.[10]

But theory is a charge which has ever been urged against revolutionists. Revolution is the child of speculation. The men of the seventeenth century are discoverers in politics. Their mark is a wider empire than that of Vasco da Gama and his king, a realm more wondrous than that of Aeëtes. But Da Gama did not steer forthright to the Indies, nor Jason to the Colchian strand, though each knew clearly the goal he sought, just as Wentworth and Selden, Falkland and Montrose, Eliot and Milton, knew the State they were steering for, though each may have wavered in his own mind as to the course, and at last parted fatally from his companions. Practical does not always mean commonplace, and in the light of their deeds it seems superfluous to discuss whether the writer of Defensio pro Populo Anglicano, the destroyer of the Campbells, or the accuser of Buckingham, were practical politicians. In their lives, in the shaping of their careers, the visionary is actualized, the ideal real, in that fidelity of soul which leaves one dead on the battlefield, another on the gibbet, thirty feet high, "honoured thus in death," as he remarked pleasantly, a third to the dreary martyrdom of the Tower, a fourth to that dread visitation, endured with stoic grandeur, and yet at times forcing from his lips the cry of anguish which thrills the verse of Samson Agonistes—

O dark, dark, dark, amid the blaze of noon,

Irrecoverably dark, total eclipse,

Without all hope of day.

But not in vain. The tireless centuries have accomplished the task these men initiated, have travelled the path they set forth in, have completed the journey which they began.

We find the same pre-occupation with some wider conception of justice, empire, and freedom in the younger Barclay, the author of Argenis, written in Latin but read in many languages, studied by Richelieu and moulding his later, wiser policy towards the Huguenots, read, above all, by Fenelon, who rises from it to write Télémaque. It meets us in the last work of Algernon Sidney, which, like Eliot's treatise, bears about it the air of a martyr's cell. We find it again explicitly in the Oceana of Harrington, in the fragmentary writings of Shaftesbury, and in actual politics it finds triumphant expression at last in the eloquence that was like a battle-cry, in the energy that at moments seems superhuman, the wisdom, the penetrating foresight, of the mightiest of all England's statesmen-orators, the elder Pitt. It burns in clear flame in the men who come after him, in his own son, only less great than his great sire; in Charles James Fox and in Windham, who in the great debate[11] of 1801 fought obstinately to save the Cape when Nelson and St. Vincent would have flung it away; in Canning, Wilberforce, in Romilly; in poets like Shelley, and thinkers like John Stuart Mill.

The revolution in parliamentary representation during the present century, a revolution which, extending over more than fifty years, from 1831 to 1884, may even be compared in its momentous consequences with the revolution of 1640-88, though constitutional in design, yet forms an integral part of the wider movement whose course across the centuries we have indicated. The leaders in this revolution, men like Russell and Grey, complete the work which Eliot, Wentworth, and Pym began. They ask the question, else unasked, they answer the question, else unanswered—How shall a people, not itself free, a people disqualified and disfranchised, become the harbinger of a new era to other peoples, or the herald of the higher freedom to the ancient races of India—Aryans, of like blood with our own, moving forever as in a twilight air, woven of the pride, the pathos, all the sombre yet undecaying memories of their fabulous past—to the Moslem populations whose "Book" proclaimed the political equality of men twelve centuries before Mirabeau spoke or the Bastille fell?

This, then, is the testimony of the Past, and the witness of the Dead is this. Thus it has arisen, this ideal, the ideal of Britain as distinct from the ideal of Rome, of Islam, or of Persia—thus it has arisen, this Empire, unexampled in present and without a precedent in former times; for Athens under Pericles was but a masked despotism, and the republic-empire of Islam passed swifter than a dream. Thus it has arisen, this Imperial Britain, from the dark Unconscious emerging to the Conscious, not like an empire of mist uprising under the wands of magic-working architects, but based on heroisms, endurances, lofty ideals frustrate yet imperishable, patient thought slowly elaborating itself through the ages—the sea-wolves' battle fury, the splendour of chivalry, the crusader's dazzling hope, the immortal ardour of Norman and Plantagenet kings, baffled, foiled, but still in other forms returning to uplift the spirit of succeeding times, the unconquered hearts of Tudor mariners rejoicing in the battle onset and the storm, the strung thought, the intense vision of statesmen of the later centuries, Eliot, Chatham, Canning, and at the last, deep-toned, far-echoing as the murmur of forests and cataracts, the sanctioning voices of enfranchised millions accepting their destiny, resolute! This is the achievement of the ages, this the greatest birth of Time. For in the empires of the past there is not an ideal, not a structural design which these warriors, monarchs, statesmen have not, deliberately or unconsciously, rejected, or, as in an alembic, transmuted to finer purposes and to nobler ends.

[1] Goethe asserts that Spinozism transmuted into a creed by analytic reflection is simply Machiavelism.

[2] The twenty-two books of Sulla's Memoirs, rerum suarum gestarum commentarii, were dedicated to his friend Lucullus; they were still in existence in the time of Tacitus and Plutarch, though the fragments which now remain serve but to mock us with regret for the loss. Of Sulla's verses—like many cultured Romans of that age, the conqueror of Caius Marius amused his leisure with writing Greek epigrams—exactly so much has survived as of the troubadour songs of Richard I of England, or of Frederick II of Jerusalem and Sicily. Sulla's remark on the young Caesar is for the youth of Caius Julius as illuminating as Richelieu's on Condé or as Pasquale Paoli's on Bonaparte.

[3] Aristotle refers only to the effect on the spectators; but the continued existence of the State makes it at once actor and spectator in the tragedy. The transforming power is thus more intimate and profound.

[4] "God in His mercy such created me

"That misery of yours attains me not,

"Nor any flame assails me of this burning."