The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Volume 20. July, 1877., by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Volume 20. July, 1877. Author: Various Release Date: March 23, 2010 [EBook #31750] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LIPPINCOTT'S MAGAZINE, JULY, 1877 *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

PHILADELPHIA:

J. B. LIPPINCOTT AND CO.

1877.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1877, by

J.B. LIPPINCOTT & CO.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Lippincott's Press,

Philadelphia.

| PAGE | ||

| Abbeys and Castles | H. James, Jr. | 434 |

| A Day's March through Finland | David Ker | 116 |

| A Few Letters | E. C. Hewitt | 111 |

| A Great Day. From the Italian of Edmondo de Amicis | 340 | |

| A Kentucky Duel | Will Wallace Harney | 578, 738 |

| A Law unto Herself | Rebecca Harding Davis | 39, 167, 292, 464, 614, 719 |

| Alfred de Musset | Sarah B. Wister | 478 |

| Among the Kabyles (Illustrated.) | Edward C. Bruce | 265, 406 |

| A Month in Sicily (Illustrated.) | Alfred T. Bacon | 649 |

| An English Easter | Henry James, Jr. | 50 |

| A Paduan Holiday (Illustrated.) | Charlotte Adams | 278 |

| A Portrait | Ita Aniol Prokop | 698 |

| A Summer Evening's Dream | Edward Bellamy | 320 |

| A Venetian of the Eighteenth Century | H. M. Benson | 347 |

| Baden and Allerheiligen (Illustrated.) | T. Adolphus Trollope | 535 |

| Brandywine, 1777 | Howard M. Jenkins | 329 |

| Captured by Cossacks. (Illustrated.) Extracts from Letters of a French Officer in 1813 | Joseph Diss Debar | 684 |

| Château Courance | John V. Sears | 235 |

| Chester and the Dee (Illustrated.) | Lady Blanche Murphy | 393, 521 |

| Communism in the United States | Austin Bierbower | 501 |

| Days of my Youth | M. T. | 712 |

| Down the Rhine (Illustrated.) | Lady Blanche Murphy | 9, 137 |

| Edinburgh Jottings (Illustrated.) | Alfred S. Gibbs | 28 |

| English Domestics and their Ways | Olive Logan | 758 |

| Folk-Lore of the Southern Negroes | William Owens | 748 |

| "For Percival." (Illustrated.) | 416, 546, 665 | |

| In a Russian "Trakteer" | David Ker | 247 |

| Irish Society in the Last Century | Eliza Wilson | 183 |

| Léonie Regnault: A Study from French Life | Mary E. Blair | 61 |

| Little Lizay | Sarah Winter Kellogg | 442 |

| London at Midsummer | H. James, Jr. | 603 |

| Madame Patterson-Bonaparte | 309 | |

| Ouida's Novels | Thomas Sergeant Perry | 732 |

| Our Blackbirds | Ernest Ingersoll | 376 |

| "Our Jook" | Henrietta H. Holdich | 494 |

| Primary and Secondary Education in France | C. H. Harding | 69 |

| Some Last Words from Sainte-Beuve | Sarah B. Wister | 104 |

| The Bass of the Potomac | W. Mackay Laffan | 455 |

| The Chef's Beefsteak | Virginia W. Johnson | 596 |

| The Church of St. Sophia | Hugh Craig | 629 |

| The Doings and Goings-on of Hired Girls | Mary Dean | 589 |

| The Flight of a Princess | W. A. Baillie-Grohman | 566 |

| The Marquis of Lossie | George Macdonald | 81, 210, 355 |

| The New Soprano | Penn Shirley | 249 |

| The Paris Cafés | Gilman C. Fisher | 202 |

| Verona. (Illustrated.) | Sarah B. Wister | 155 |

| Vina's "Ole Man." (Illustrated.) | Lizzie W. Champney | 194 |

Literature of the Day, comprising Reviews of the following Works:

| Avery, Benjamin Parke—Californian Pictures in Prose and Verse | 775 |

| Baker, M. A., James—Turkey | 135 |

| Burroughs, John—Birds and Poets | 516 |

| Dodge, R. I.—The Plains of the Great West and their Inhabitants | 262 |

| Doudan, X.—Mélanges et Lettres | 646 |

| Field, Marie E.—The Wings of Courage | 776 |

| Gill, W. F.—The Life of Edgar Allan Poe | 518 |

| Concourt, de, Edmond and Jules—Madame Gervaisais | 388 |

| Gréville, Henry—Les Koumiassine | 519 |

| Hoffman, Wickham—Camp, Court and Siege | 261 |

| Kismet | 392 |

| McCoan, J. C.—Egypt as it Is | 774 |

| Mazade, de, Charles—The Life of Count Cavour | 772 |

| Migerka, Catherine—Briefe aus Philadelphia (1876) an eine Freundin | 643 |

| Nimport | 642 |

| Parkman, Francis—Count Frontenac and New France under Louis XIV | 641 |

| Price, Major Sir Rose Lambart—The Two Americas | 132 |

| Procter, Bryan Waller (Barry Cornwall)—An Autobiographical Fragment and Biographical Notes | 133 |

| Reid, T. Wemyss—Charlotte Brontë | 390 |

| Robinson, Leora B.—Patsy | 776 |

| Sherwood, Mary Neal—Jack. From the French of Alphonse Daudet | 645 |

| Squier, E. George—Peru | 259 |

| Synge, W. W. Follett—Olivia Raleigh | 518 |

| Wheaton, Campbell—Six Sinners; or, School-Days in Bantam Valley | 776 |

Our Monthly Gossip, comprising the following Articles:

A Cheering Sign, 258; A Crying Evil, 771; A Day at the Paris Conservatoire, 512; A Missing Item, 770; A Neglected Branch of Philology, 385; Another Defunct Monopoly, 386; Artistic Jenkinsism, 640; Brigham Young and Mormonism, 514; Fernan Caballero, 761; Foreign Leaders in Russia and Turkey, 765; François Buloz, 382; Friend Abner in the North-West, 254; How shall we Call the Birds? 256; Katerfelto in Repose, 387; "Les Naufragés de Calais," 637; Miridite Courtship, 253; Notes from Moscow, 509; Punching the Drinks, 130; Realistic Art, 639; Russian and Turkish Music, 636; The Coming Elections in France, 127; The Dead of Paris, 122; The Departure of the Imperial Guards, 768; The Education of Women in India, 515; The Modern French Novelists, 379; The Nautch-Dancers of India, 132; The Octroi, 763; The Religious Struggle at Geneva, 125; Von Moltke in Turkey, 129; Water-Lilies, 384.

Poetry:

| A Wish | Henrietta R. Eliot | 308 |

| Fog | Emma Lazarus | 207 |

| For Another | S. M. B. Piatt | 405 |

| From the Flats | Sidney Lanier | 115 |

| "God's Poor" | E. R. Champlin | 711 |

| Heine (Buch der Lieder) | Charles Quiet | 354 |

| Selim | Annie Porter | 755 |

| Song | Oscar Laighton | 545 |

| Sven Duva. From the Swedish of Johan Ludvig Runeberg | C. Rosell | 611 |

| The Bee | Sidney Lanier | 493 |

| The Chrysalis of a Bookworm | Maurice F. Egan | 463 |

| The Dream of St. Theresa | Epes Sargent | 565 |

| The Elixir | Emma Lazarus | 60 |

| The Marsh | S. Weir Mitchell | 245 |

| The Sweetener | Mary B. Dodge | 49 |

| To Sleep | Emilie Poulsson | 201 |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1877, by J. B. Lippincott & Co., in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

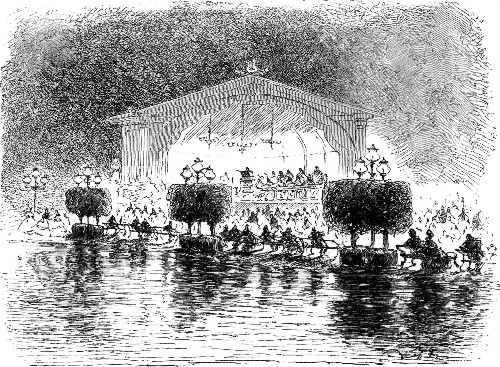

EVENING CONCERT AT WIESBADEN.

EVENING CONCERT AT WIESBADEN.

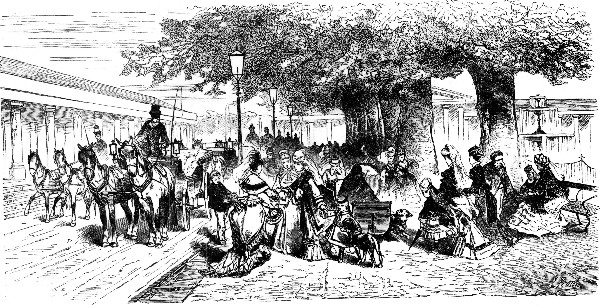

Wiesbaden (the "Meadow-Bath"), though an inland town, partakes of some of the Rhine characteristics, though even if it did not, its notoriety as a spa would be enough to make some mention of it necessary. Its promenade and Kurhaus, its society, evening concerts, alleys of beautiful plane trees, its frequent illuminations with Bengal lights, reddening the classic peristyles and fountains with which modern taste has decked the town, its[Pg 10] airy Moorish pavilion over the springs, and its beautiful Greek chapel with fire-gilt domes, each surmounted by a double cross connected with the dome by gilt chains—a chapel built by the duke Adolph of Nassau in memory of his wife, Elizabeth Michaelovna, a Russian princess,—are things that almost every American traveler remembers, not to mention the Neroberger wine grown in the neighborhood.

Schlangenbad, a less well-known bathing-place, is a favorite goal of Wiesbaden excursionists, for a path through dense beech woods leads from the stirring town to the quieter "woman's republic," where, before sovereigns in incognito came to patronize it, there had long been a monopoly of its charms by the wives and daughters of rich men, bankers, councilors, noblemen, etc., and also by a set of the higher clergy. The waters were famous for their sedative qualities, building up the nervous system, and, it is said, also beautifying the skin. Some credulous persons traced the name of the "Serpents' Bath" to the fact that snakes lurked in the springs and gave the waters their healing powers; but as the neighborhood abounds in a small harmless kind of reptile, this is the more obvious reason for the name. I spent a pleasant ten days at Schlangenbad twelve or thirteen years ago, when many of the German sovereigns preferred it for its quiet to the larger and noisier resorts, and remember with special pleasure meeting with fields of Scotch heather encircled by beech and chestnut woods, with ferny, rocky nooks such as—when it is in Germany that you find them—suggest fairies, and with a curious village church, just restored by a rich English Catholic, since dead, who lived in Brussels and devoted his fortune to religious purposes all over the world. This church was chiefly interesting as a specimen of what country churches were in the Middle Ages, having been restored in the style common to those days. It was entirely of stone, within as well as without, and I remember no painting on the walls. The "tabernacle," instead of being placed on the altar, as is the custom in most churches now, and has been for two or three hundred years, was, according to the old German custom, a separate shrine, with a little tapering carved spire, placed in the corner of the choir, with a red lamp burning before it. Here, as in most of the Rhine neighborhoods, the people are mainly Catholics, but in places where summer guests of all nations and religions are gathered there is often a friendly arrangement by which the same building is used for the services of two or three faiths. There was, I think, one such at Schlangenbad, where Catholic, Lutheran and Anglican services were successively held every Sunday morning; and in another place, where a large Catholic church has since been built, the old church was divided down the middle of the nave by a wooden partition about the height of a man's head, and Catholic and Protestant had each a side permanently assigned to them for their services. This kind of practical toleration, probably in the beginning the result of poverty on both sides, but at any rate creditable to its practicers, was hardly to be found anywhere outside of Germany. I remember hearing of the sisters of one of the pope's German prelates, Monsignor Prince Hohenlohe, who were Lutherans, embroidering ecclesiastical vestments and altar-linen for their brother with as much delight as if he and they believed alike; and (though this is anything but praiseworthy, for it was prompted by policy and not by toleration) it was a custom of the smaller German princes to bring their daughters up in the vaguest belief in vital truths, in order that when they married they might become whatever their husbands happened to be, whether Lutheran, Anglican, Catholic or Greek. The events of the last few years, however, have changed all this, and religious strife is as energetic in Germany as it was at one time in Italy: people must take sides, and this outward, easy-going old life has disappeared before the novel kind of persecution sanctioned by the Falk laws. Some persons even think the present state of things traceable to that same toleration, leading, as it did in many cases, to lukewarmness and indifferentism in religion. Strange phases for a fanatical Germany to pass through, and a stranger commentary on the words of Saint Remigius to Clovis, the first Frankish Christian king: "Burn that which thou hast worshiped, and worship that which thou hast burnt"![Pg 11]

PROMENADE AT WIESBADEN.

PROMENADE AT WIESBADEN.

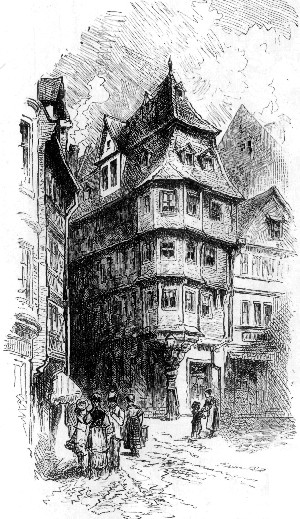

LUTHER'S HOUSE AT FRANKFORT.

LUTHER'S HOUSE AT FRANKFORT.

Schwalbach is another of Wiesbaden's handmaidens—a pleasant, rather quiet spot, from which, if you please, you can follow the Main to the abode of sparkling hock or the vinehills of Hochheim, the property of the church which crowns the heights. This is at the entrance of the Roman-named Taunus Mountains, where there are bathing-places, ruined castles, ancient bridges, plenty of legends, and, above all, dark solemn old chestnut forests. But we have a long way to go, and must not linger on our road to the free imperial city of Frankfort, with its past history and present importance. Here too I have some personal remembrances, though hurried ones. The hotel itself—what a relief such hotels are from the modern ones with electric bells and elevators and fifteen stories!—was an old patrician house ample, roomy, dignified, and each room had some individuality, notwithstanding the needful amount of transformation from its old self. It was a dull, wet day when we arrived, and next morning we went to the cathedral, Pepin's foundation, of which I remember, however, less than of the great hall in the Römer building where the Diets sat and where the "Golden Bull" is still kept—a hall now magnificently and appropriately frescoed with subjects from German history. Then the far-famed Judengasse, a street where the first Rothschild's mother lived till within a score of years ago, and where now, among the dark, crazy tenements, so delightful to the artist's eye, there glitters one of the most gorgeously-adorned synagogues in Europe. A change indeed from the times when Jews were hunted and hooted at in these proud, fanatical cities, which were not above robbing them and making use of them even while they jeered and persecuted! The great place in front of the emperor's hall was the appointed ground for tournaments, and as we lounge on we come to a queer house, with its lowest corner cut away and the oriel window above supported on one massive pillar: from that window tradition says that Luther addressed the people just before starting for Worms to meet the Diet. This other house has a more modern[Pg 13] look: it is Goethe's birthplace, the house where the noted housekeeper and accomplished hostess, "Frau Rath"—or "Madam Councilor," as she was called—gathered round her those stately parties that are special to the great free cities of olden trade. Frankfort has not lost her reputation in this line: her merchants and civic functionaries still form an aristocracy, callings as well as fortunes are hereditary, and if some modern elements have crept in, they have not yet superseded the old. The regattas and boating-parties on the Main remind one of the stir on the banks of the Thames between Richmond and Twickenham, where so many "city men" have lovely retired homes; but Frankfort has its Kew Gardens also, where tropical flora, tree-ferns and palms, in immense conservatories, make perpetual summer, while the Zoological Garden and the bands that play there are another point of attraction. Still, I think one more willingly seeks the older parts—the Ashtree Gate, with its machicolated tower and turrets, the only remnants of the fortifications; the old cemetery, where Goethe's mother is buried; and the old bridge over the Main, with the statue of Charlemagne bearing the globe of empire in his hand, which an innocent countryman from the neighboring village of Sachsenhausen mistook for the man who invented the Aeppelwei, a favorite drink of Frankfort. This bridge has another curiosity—a gilt cock on an iron rod, commemorating the usual legend of the "first living thing" sent across to cheat the devil, who had extorted such a promise from the architect. But although the ancient remains are attractive, we must not forget the Bethmann Museum, with its treasure of Dannecker's Ariadne, and the Städel Art Institute, both the legacies of public-spirited merchants to their native town; the Bourse, where a business hardly second to any in London is done; and the memory of so many great minds of modern times—Börne, Brentano, Bettina von Arnim, Feurbach, Savigny, Schlossen, etc. The Roman remains at Oberürzel in the neighborhood ought to have a chapter to themselves, forming as they do a miniature Pompeii, but the Rhine and its best scenery calls us away from its great tributary, and we already begin to feel the witchery which a popular poet has expressed in these lines, supposed to be a warning from a father to a wandering son:

JOHN WOLFGANG GOETHE.

JOHN WOLFGANG GOETHE.

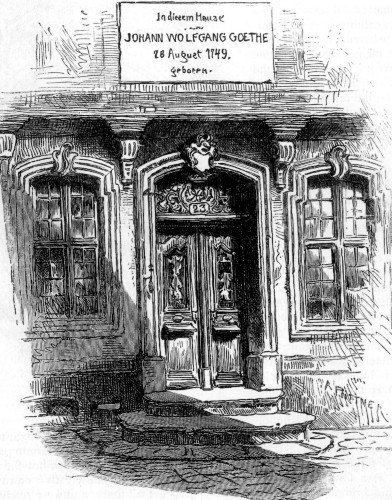

GOETHE'S BIRTHPLACE.

GOETHE'S BIRTHPLACE.

This is the Rheingau, the most beautiful valley of rocks and bed of rapids which occurs during the whole course of the river—the region most crowded with legends and castles, and most frequented by strangers by railroad and steamboat. The right bank is at first the only one that calls for attention, dotted as it is with townlets, each nestled in orchards, gardens and vineyards, with a church and steeple, and terraces of odd, over-hanging houses; little stone arbors trellised with grapevines; great crosses and statues of patron saints in the warm, soft-toned red sandstone of the country; fishermen's taverns, with most of the business done outside under the trees or vine-covered piazza; little, busy wharfs and works, aping joyfully the bustle of large seaports, and succeeding in miniature; and perhaps a burgomaster's garden, where that portly and pleasant functionary does not disdain to keep a tavern and serve his customers himself, as at Walluf.[Pg 15]

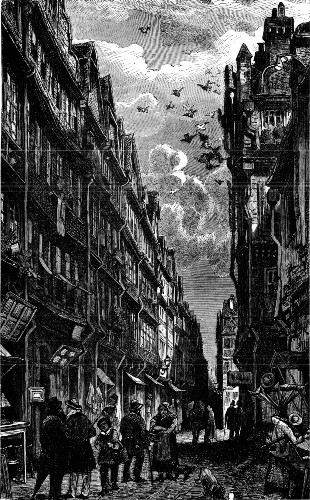

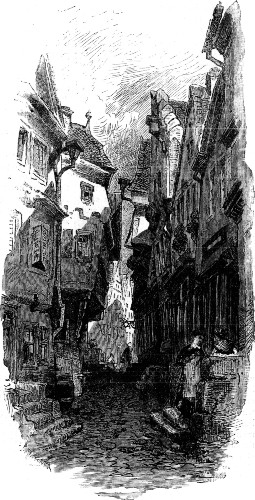

JUDENGASSE AT FRANKFORT.

JUDENGASSE AT FRANKFORT.

At Rauenthal (a "valley" placed on high hills) we find the last new claimant to the supremacy among Rhine wines, at least since the Paris Exhibition, when the medal of honor was awarded to Rauenthal, which has ended in bringing many hundreds of curious connoisseurs to test the merits of the grape where it grows. Now comes a whole host of villages on either side of the river, famous through their wines—Steinberg, the "golden beaker;" Scharfenstein, whose namesake castle was the refuge of the warlike archbishops of Mayence, the stumbling-block of the archbishops of Trèves, called "the Lion of Luxembourg," and lastly the prey of the terrible Swedes, who in German stories play the part of Cossacks and Bashi-Bazouks; Marcobrunnen, with its classical-looking ruin of a fountain hidden among vineyards; Hattenheim, Hallgarten, Gräfenberg; and Eberbach, formerly an abbey, known for its "cabinet" wine, the hall-mark of those times, and its legends of Saint Bernard, for whom a boar ploughed a circle with his tusks to show the spot where the saint should build a monastery, and afterward tossed great stones thither for the foundation, while angels helped to build the upper walls. Eberbach is rather deserted than ruined. It was a good deal shattered in the Peasants' War at the time of the Reformation, when the insurgents emptied the huge cask in which the whole of the Steinberg wine-harvest was stored; but since 1803, when it was made over to the neighboring wine-growers, it has remained pretty well unharmed; and its twelfth-century chapel, full of monuments; its refectory, now the press-house, with its columns and capitals nearly perfect; its cellars, where every year more wine is given away than is stored—i. e., all that which is not "cabinet-worthy"—as in the tulip-mania, when thousands of roots were thrown away as worthless, which yet had all the natural merit of lovely coloring and form,—make Eberbach well worth seeing.

Next comes Johannisberg, with its vineyards dating back to the tenth century, when Abbot Rabanus of Fulda cultivated the grape and Archbishop Ruthard of Mayence built a monastery, dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, which for centuries was owner and guardian of the most noted Rhine vintage; but abuses within and wars without have made an end of this state of things, and Albert of Brandenburg's raid on the monks' cellars has been more steadily supplemented by the pressure of milder but no less efficient means of destruction. When Napoleon saw this tract of land and offered it to General Kellermann, who had admired its beauty, he is said to have received a worthy and a bold answer. "I thank Your Majesty," said the marshal, "but the receiver is as bad as the thief." The less scrupulous Metternich became its owner, giving for it, however, an equivalent of arable and wood land. The Metternich who for years was Austrian ambassador at Paris during the brilliant time of the Second Empire, and whose fast and eccentric wife daily astonished society, is now owner of the peerless Johannisberg vineyards, among which is his country-house. Goethe's friends, the Lade and Brentano families, lived in this neighborhood, and the historian Nicholas Vogt lies buried in the Metternich chapel, though his heart, by his special desire, is laid in a silver casket within the rocks of Bingen, with a little iron cross marking the spot. At Geisenheim we are near two convents which as early as 1468 had printing-presses in active use, and the mysterious square tower of Rüdesheim, which brings all sorts of suppositions to our mind, though the beauty of the wayside crosses, the tall gabled roofs, the crumbling walls, the fantastically-shaped rocks, getting higher and higher on each side, and the perpetual winding of the river, are enough to keep the eye fixed on the mere landscape. At the windows, balconies and arbors sit pretty, ruddy girls waving their handkerchiefs to the unknown "men and brethren" on board the steamers and the trains; and well they may, if this be a good omen, for here is the "Iron Gate" of the Rhine, and the water bubbles and froths in miniature whirlpools as we near what is called the "Bingen Hole."

As we have passed the mouth of the Stein and recollected the rhyme of Schrödter in his King Wine's Triumph[Pg 17]—

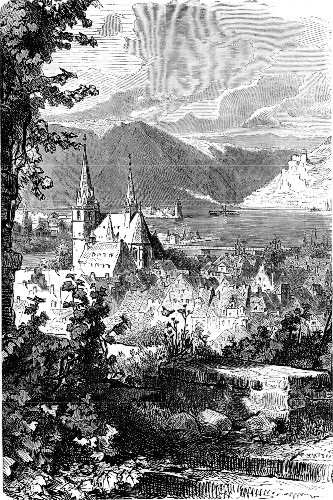

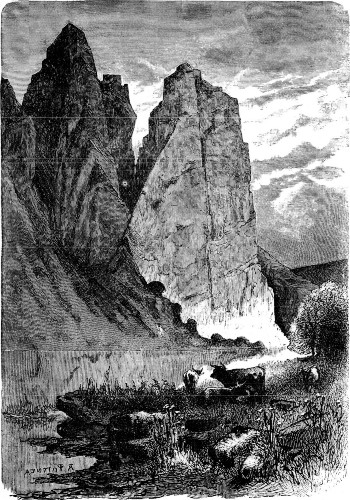

RÜDESHEIM.

RÜDESHEIM.

so now we peer up one of the clefts in the rocks and see the Nahe ploughing its way along to meet the great river. Just commanding the mouth is Klopp Castle, and not far warlike Bingen, a rich burgher-city, plundered and half destroyed in every war from those of the fourteenth to those of the eighteenth century, while Klopp too claims to have been battered and bruised even in the thirteenth century, but is better known as the scene of the emperor Henry IV.'s betrayal to the Church authorities by his son, who treacherously invited him to visit him here by night. A little way up the river Nahe, where the character of the people changes from the lightheartedness of the Rhine proper to a steadiness and earnestness somewhat in keeping with the sterner and more mountainous aspect of the country, is Kreuznach, (or "Crossnear"), now a bathing-resort, and once a village founded by the first Christian missionaries round the first cross under whose shadow they preached the gospel. Sponheim Castle, once the abode of Trithemius, or Abbot John of Trittenheim, a famous chronicler and scholar, reminds us of the brave butcher of Kreuznach, Michael Mort, whose faithfulness to his lawful lord when beset by pretenders to his title in his own family won for the guild of butchers certain privileges which they have retained ever since; and Rheingrafenstein, where the ruins are hardly distinguishable from the tossed masses of porphyry rock on which they are perched, tells us the story of Boos von Waldeck's wager with the lord of the castle to drink a courier's top-boot full of Rhine wine at one draught—a feat which he is said to have successfully accomplished, making himself surely a fit companion for Odin in Walhalla; but his reward on earth was more substantial, for he won thereby the village of Hüffelsheim and all its belongings. In a less romantic situation stands Ebernburg, so called from the boar which during a siege the hungry but indomitable defenders of the castle paraded again and again before the eyes of the besiegers, whose only hope lay in starving out the garrison—the property of the Sickengens, whose ancestor Franz played a prominent part in the Reformation and gave an asylum in these very halls to Bucer, Melanchthon, Œcolampadius and Ulrich von Hütten. Past Rothenfels, where towering rocks hem in the stream, like the Wye banks in Arthur's country on the Welsh borders; the scattered stones of Disibodenberg, the Irish missionary's namesake convent, which afterward passed into the hands of the Cistercians; Dhaum Castle and Oberstein Church, these two with their legends, the first accounting for a bas-relief in the great hall representing an ape rocking a child, the heir of the house, in the depths of a forest, and giving him an apple to eat,—we come to a cluster of castles which are the classical ground of the Nahe Valley. The very rocks seem not only crowned but honeycombed with buildings: chapels stand on jutting crags; houses, heaped as it were one on the roof of the other, climb up their rough sides, and the roofs themselves have taken their cue from the rocks, and have three or four irregular lines of tiny windows ridging and bulging them out.

Taking boat again at Bingen, and getting safely through the Rhine "Hell Gate," the "Hole," whose terrors seem as poetic as those of the Lorelei, we pass the famous Mouse Tower, and opposite it the ruined Ehrenfels; Assmanshausen, with its dark-colored wine and its custom of a May or Pentecost feast, when thousands of merry Rhinelanders spend the day in the woods, dancing, drinking and singing, baskets outspread in modified and dainty pic-nic fashion, torches lit at night and bands playing or mighty choruses resounding through the woods; St. Clement's Chapel, just curtained from the river by a grove of old poplars and overshadowed by a ruin with a hundred eyes (or windows), while among the thickly-planted, crooked crosses of its churchyard old peasant-women and children run or totter, the first telling their beads, the second gathering flowers,[Pg 19] and none perhaps remembering that the chapel was built by the survivors of the families of the robber-knights of Rheinstein (one of the loveliest of Rhine ruins) and three other confederated castles, whom Rudolph of Habsburg treated, rightly enough, according to the Lynch law of his time. They were hung wherever found, but their pious relations did not forget to bury them and atone for them as seemingly as might be.

BINGEN, FROM KLOPP CASTLE.

BINGEN, FROM KLOPP CASTLE.

Bacharach, if it were not famed in Germany for its wine, according to the old rhyme declaring that

would or ought to be noticed for its wealth of old houses and its many architectural beauties, from the ruined (or rather unfinished) chapel of St. Werner, now a wine-press house, bowered in trees and surrounded by a later growth of crosses and tombstones, to the meanest little house crowding its neighbor that it may bathe its doorstep in the river—houses that when their owners built and patched them from generation to generation little dreamt that they would stand and draw the artist's eye when the castle was in ruins. Similarly, the many serious historical incidents that took place in Bacharach have lived less long in the memory of inhabitants and visitors than the love-story connected with the ruined castle—that of Agnes, the daughter of the count of this place and niece of the great Barbarossa, whom her father shut up here with her mother to be out of the way of her lover, Henry of Braunschweig. The latter, a Guelph (while the count was a Ghibelline), managed, however, to defeat the father's plans: the mother helped the lovers, and a priest was smuggled into the castle to perform the marriage, which the father, after a useless outburst of rage, wisely acknowledged as valid. The coloring of many buildings in this part of the Rhineland is very beautiful, the red sandstone of the neighborhood being one of the most picturesque of building materials. Statues and crosses, as well as churches and castles, are built of it, and even the rocks have so appealed by their formation to the imagination of the people that at Schönburg we meet with a legend of seven sisters, daughters of that family whose hero, Marshal Schomburg, the friend and right hand of William of Orange, lies buried in Westminster Abbey, honored as marshal of France, peer of Great Britain and grandee of Portugal, and who, for their haughtiness toward their lovers, were turned into seven rocks, through part of which now runs the irreverent steam-engine, ploughing through the tunnel that cuts off a corner where the river bends again.

Now comes the gray rock where, as all the world knows, the Lorelei lives, but as that graceful myth is familiar to all, we will hurry past the mermaid's home, where so much salmon used to be caught that the very servants of the neighboring monastery of St. Goar were forbidden to eat salmon more than three times a week, to go and take a glimpse of St. Goarshausen, with its convent founded in the seventh century by one of the first Celtic missionaries, and its legend of the spider who remedied the carelessness of the brother cellarer when he left the bung out of Charlemagne's great wine-cask by quickly spinning across the opening a web thick enough to stop the flow of wine. A curious relic of olden time and humor is shown in the cellar—an iron collar, grim-looking, but more innocent than its looks, for it was used only to pin the unwary visitor to the wall while a choice between a "baptism" of water and wine was given him. The custom dates back to Charlemagne's time. Those who, thinking to choose the least evil of the two, gave their voice for the water, had an ample and unexpected shower-bath, while the wine-drinkers were crowned with some tinseled wreath and given a large tankard to empty. On the heights above the convent stood the "Cat" watching the "Mouse" on the opposite bank above Wellmich, the two names commemorating an insolent message sent by Count John III. of the castle of Neu-Katzellenbogen to Archbishop Kuno of Falkenstein, the builder of the castle of Thurnberg, "that he greeted him and hoped he would take good care of his mouse, that his (John's) cat might not eat it up." And now we pass a chain of castles, ruins and villages; rocks with such names as the Prince's Head; lead, copper and silver works, with all the activity of modern[Pg 21] life, stuck on like a puppet-show to the background of a solemn old picture, a rocky, solitary island, "The Two Brothers," the twin castles of Liebenstein and Sternberg, the same which Bulwer has immortalized in his Pilgrims of the Rhine, and at their feet, close to the shore, a modern-looking building, the former Redemptorist convent of Bornhofen. As we step out there is a rude quay, four large old trees and a wall with a pinnacled niche, and then we meet a boatful of pilgrims with their banners, for this is one of the shrines that are still frequented, notwithstanding many difficulties—notwithstanding that the priests were driven out of the convent some time ago, and that the place is in lay hands; not, however, unfriendly hands, for a Catholic German nobleman, married[Pg 22] to a Scotch woman, bought the house and church, and endeavored, as under the shield of "private property," to preserve it for the use of the Catholic population of the neighborhood. Last summer an English Catholic family rented the house, and a comfortable home was established in the large, bare building attached to the church, where is still kept the Gnadenbild, or "Grace image," which is the object of the pilgrimage—a figure of the Blessed Virgin holding her dead Son upon her knees. These English tenants brought a private chaplain with them, but, despite their privileges as English subjects, I believe there was some trouble with the government authorities. However, they had mass said for them at first in the church on weekdays. A priest from Camp, the neighboring post-town, was allowed to come once in a week to say mass for the people, but with locked doors, and on other days the service was also held in the same way, though a few of the country-people always managed to get in quietly before the doors were shut. On Sundays mass was said for the strangers and their household only in a little oratory up in the attics, which had a window looking into the church near the roof of the chancel. One of them describes "our drawing-room in the corner of the top floor, overlooking the river," and "our life ... studying German, reading and writing in the morning, dining early, walking out in the evening, tea-supper when we come home.... There are such pretty walks in the ravines and hills, in woods and vineyards, and to the castles above and higher hills beyond! We brought one man and a maid, who do not know German, and found two German servants in the house, who do everything.... It is curious how cheaply we live here; the German cook left here does everything for us, and we are saying she makes us much better soups and omelettes and souffles than any London cook." Now, as these three things happen to be special tests of a cook's skill, this praise from an Englishman should somewhat rebuke travelers who can find no word too vile for "German cookery."

RHEINGRAFENSTEIN.

RHEINGRAFENSTEIN.

The time of the yearly pilgrimage came round during the stay of these strangers, "and pilgrims came from Coblenz, a four hours' walk (in mid-August and the temperature constantly in the nineties), on the opposite side of the river, singing and chanting as they came, and crossed the river here in boats. High mass was at half-past nine (in the morning) and benediction at half-past one, immediately after which they returned in boats down the stream much more quickly. The day before was a more local pilgrimage: mass and benediction were at eight, but pilgrims came about all the morning." Later on, when the great heat had brought "premature autumn tints to the trees and burnt up the grass," the English family made some excursions in the neighborhood, and in one place they came to a "forest and a large tract of tall trees," but this was exceptional, as the soil is not deep enough to grow large timber, and the woods are chiefly low underwood. The grapes were small, and on the 22d of August they tasted the first plateful at Stolzenfels, an old castle restored by the queen-dowager of Prussia, and now the property of the empress of Germany. "The view from it is lovely up and down the river, and the situation splendid—about four hundred feet above the river, with high wooded hills behind, just opposite the Lahn where it falls into the Rhine." Wolfgang Müller describes Stolzenfels as a beautiful specimen of the old German style, with a broad smooth road leading up over drawbridges and moats, with mullioned windows and machicolated towers, and an artistic open staircase intersected by three pointed arches, and looking into an inner courtyard, with a fountain surrounded by broad-leaved tropical water-plants. The sight of a combination of antique dignity with correct modern taste is a delight so seldom experienced that it is worth while dwelling on this pleasant fact as brought out in the restoration of Stolzenfels, the "Proud Rock." And that the Rhinelanders are proud of their river is no wonder when strangers can talk about it thus: "The Rhine is a river which grows[Pg 23] upon you, living in a pretty part of its course:... its less beauteous parts have their own attractions to the natives, and its beauties, perhaps exaggerated, unfold greatly the more you explore them, not to be seen by a rushing tourist up and down the stream by rail or by boat, but sought out and contemplated from its heights and windings.... In fact, the pretty part of its course is from Bingen to Bonn. Here we are in a wonderfully winding gorge, containing nearly all its picturesque old castles, uninterrupted by any flat. The stream is rapid enough, four miles an hour or more—not equal to the Rhone at Geneva, but like that river in France. One does not wonder at the Germans being enthusiastic over their river, as the Romans were over the yellow Tiber."

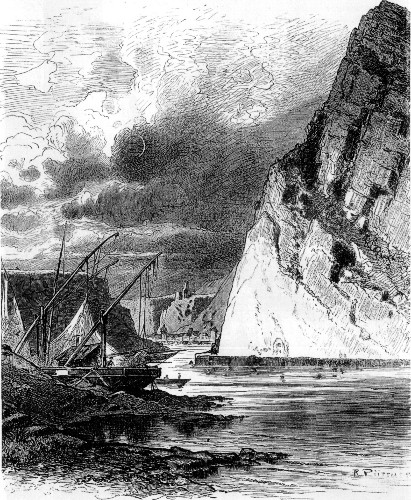

MOUSE-TOWER (OR BISHOP HATTO'S TOWER) AND EHRENFELS.

MOUSE-TOWER (OR BISHOP HATTO'S TOWER) AND EHRENFELS.

THE LORELEI ROCK.

THE LORELEI ROCK.

Other excursions were made by the Bornhofen visitors, one up a hill on the opposite side, over sixteen hundred feet high, whence a fine distant view of the Mosel Valley was seen, and one also to the church of St. Apollinaris, at Remagen, at some distance down the river, where are "some fine frescoes by German[Pg 25] artists covering the whole interior of the church. One artist painted four or five large ones of the Crucifixion, Resurrection and other events relating to the life of Our Lord; a second several of the life of St. Apollinaris, and two others some of Our Lady and various saints, one set being patron saints of the founder's children, whom I think we saw at Baden—Carl Egon, Count Fürstenberg-Stammheim.... The family-house stands close to the church, or one of his houses, and seems to have been made into a Franciscan convent: the monks are now banished and the church deserted, a custode (guardian) in charge. We went one day to Limburg to see the bishop of this diocese, a dear old man who only speaks German, so E—— and C—— carried on all the conversation. The cathedral is a fine old Norman building with seven towers: it is undergoing restoration, and the remains of old frescoes under the whitewash are the ground-work of renewed ones. Where an old bit is perfect enough it is left."

A STREET IN LIMBURG.

A STREET IN LIMBURG.

Camp, a mile from Bornhofen, is an insignificant place enough, but claiming to have been a Roman camp, and having an old convent as picturesque as those of far-famed and much-visited towns. The same irregular windows, roofed turrets springing up by the side of tall gables, a corner-shrine of Our Lady and Child, with vines and ivy making a niche for it, mossy steps, a broken wall with trailing vines and steep stone-roofed recess, probably an old niche,—such is a sketch of[Pg 26] what would make a thoroughly good picture; but in this land there are so many such that one grows too familiar with them to care for the sight. Nearly opposite is Boppard, a busy ancient town, with a parish church beautiful enough for a cathedral—St. Severin's church, with carved choir-stalls and a double nave—and the old Benedictine monastery for women, now a cold-water cure establishment. Boppard has its legend of a shadowy Templar and a faithless bridegroom challenged by the former, who turned out to be the forsaken bride herself; but of these legends, one so like the other, this part of the Rhine is full. The next winding of the stream shows us Oberspay, with a romantic tavern, carved pillars supporting a windowed porch, and a sprawling kind of roof; the "King's Stool," a modern restoration of the mediæval pulpit or platform of stone supported by pillars, with eighteen steps and a circumference of forty ells, where the Rhenish prince-archbishops met to choose the temporal sovereigns who were in part their vassals; Oberlahnstein, a town famous for its possession in perfect repair of the ancient fortifications; Lahneck, now a private residence, once the property of the Templars; Stolzenfels, of which we have anticipated a glimpse; the island of Oberwörth, with an old convent of St. Magdalen, and in the distance frowning Ehrenbreitstein, the fortress of Coblenz.

Turning up the course of the Lahn, we get to the neighborhood of a small but famous bathing-place, Ems, the cradle of the Franco-Prussian war, where the house in which Emperor William lodged is now shown as an historic memento, and effaces the interest due to the old gambling Kursaal. The English chapel, a beautiful small stone building already ivied; the old synagogue, a plain whitewashed building, where the service is conducted in an orthodox but not very attractive manner; the pretty fern- and heather-covered woods, through which you ride on donkeyback; the gardens, where a Parisian-dressed crowd airs itself late in the afternoon; all the well-known adjuncts of a spa, and the most delightful baths I ever saw, where in clean little chambers you step down three steps into an ample marble basin sunk in the floor, and may almost fancy yourself a luxurious Roman of the days of Diocletian,—such is Ems. But its environs are full of wider interest. There is Castle Schaumburg, where for twenty years the archduke Stephen of Austria, palatine of Hungary, led a useful and retired life, making his house as orderly and seemly as an English manor-house, and more interesting to the strangers, whose visits he encouraged, by the collections of minerals, plants, shells and stuffed animals and the miniature zoological and botanical gardens which he kept up and often added to. I spent a day there thirteen years ago, ten years before he died, lamented by his poor neighbors, to whom he was a visible providence. Another house of great interest is the old Stein mansion in the little town of Nassau, the home of the upright and patriotic minister of that name, whose memory is a household word in Germany. The present house is a comfortable modern one—a château in the French sense of the word—but the old shattered tower above the town is the cradle of the family. At the village of Frücht is the family-vault and the great man's monument, a modern Gothic canopy, somewhat bald and characterless, but bearing a fine statue of Stein by Schwanthaler, and an inscription in praise of the "unbending son of bowed-down Fatherland." He came of a good stock, for thus runs his father's funeral inscription, in five alliterative German rhymes. I can give it but lamely:

Stein was born in the house where he retired to spend his last years in study: his grave and pious nature is shown in the mottoes with which he adorned his home: "A tower of strength is our God" over the house-door, and in his library, above his books and busts and gathering of life-memorials, "Confidence in God, singleness of mind and righteousness."[Pg 27] His contemporaries called him, in a play upon his name which, as such things go, was not bad, "The foundation-stone of right, the stumbling-stone of the wicked, and the precious stone of Germany." Arnstein and its old convent, now occupied by a solitary priest: Balduinenstein and its rough-hewn, cyclopean-looking ruin, standing over the mossy picturesque water-mill; the marble-quarries near Schaumburg, worked by convicts; Diez and its conglomeration of houses like a puzzle endowed with life,—are all on the way to Limburg, the episcopal town, old and tortuous, sleepy and alluring, with its shady streets, its cathedral of St. George and its monument of the lion-hearted Conrad or Kuno, surnamed Shortbold (Kurzbold), a nephew of Emperor Conrad, a genuine woman-hater, a man of giant strength but dwarfish height, who is said to have once strangled a lion, and at another time sunk a boatful of men with one blow of his spear. The cathedral, the same visited by our Bornhofen friends, has other treasures—carved stalls and a magnificent image of Our Lord of the sixteenth century, a Gothic baptismal font and a richly-sculptured tabernacle, as well as a much older image of St. George and the Dragon, supposed by some to refer to the legendary existence of monsters in the days when Limburg was heathen. Some such idea seems also not to have been remote from the fancy of the mediæval sculptor who adorned the brave Conrad's monument with such elaborately monstrous figures: it was evidently no lack of skill and delicacy that dictated such a choice of supporters, for the figure of the hero is lifelike, dignified and faithful to the minute description of his features and stature left us by his chronicler, while the beauty of the leaf-border of the slab and of the capitals of the short pillars is such as to excite the envy of our best modern carvers.

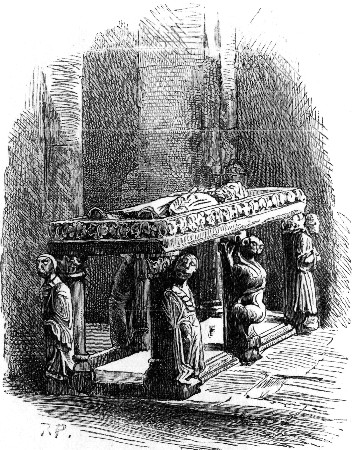

CONRAD'S MONUMENT, LIMBURG CATHEDRAL.

CONRAD'S MONUMENT, LIMBURG CATHEDRAL.

Lady Blanche Murphy.

Whenever Scott's landau went up the Canongate, his coachman knew without special instructions that the pace must be a walk; and no funeral, says Lockhart, ever moved more slowly, for wherever the great enthusiast might turn his gaze there was recalled to his mind some tradition of blood and mystery at which his eye would sparkle and his cheek glow. How by the force of his genius he inoculated the world with his enthusiasm about the semi-savage Scotia of the past is a well-known story: thousands of tourists, more or less struck with the Scott madness, yearly wander through the streets of old Edinburgh; and although within the quarter of a century since Sir Walter's death many memorials of the past have been swept away under the pressure of utility or necessity, the Old Town still poses remarkably well, and, gathering her rags and tatters about her, contrives to keep up a strikingly picturesque appearance.

THE CASTLE AND ALLAN RAMSAY'S HOUSE.

THE CASTLE AND ALLAN RAMSAY'S HOUSE.

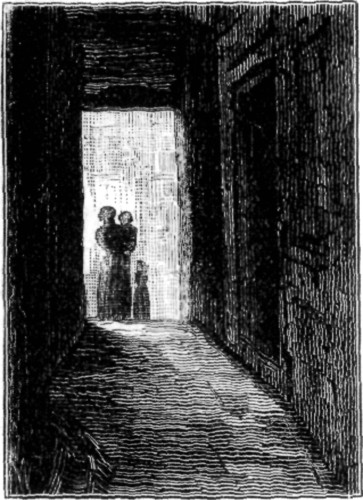

The Old Town of Edinburgh is built upon a wedge-shaped hill, the Castle occupying the highest point, the head of the wedge, and the town extending along the crest, which slopes gradually down toward the east,[Pg 29] to Holyrood Palace in the plain. Lawnmarket, High street and Canongate now form one continuous street, which, running along the crest of the hill, may be considered as the backbone of the town, with wynds and closes radiating on each side like the spines of the vertebræ. The closes are courts, culs-de-sac—the wynds, thoroughfares. These streets—courts where, in the past, lived the nobility and gentry of Edinburgh—are now, for the most part, given up to squalor and misery, and look like stage-scenes perpetually "set" for melodramatic horrors. The late Dr. Thomas Guthrie, whose parish included a large portion of this Egypt, used often to illustrate his eloquence with graphic word-pictures suggested by his experiences in these dark places. "The unfurnished floor," he writes, "the begrimed and naked walls, the stifling, sickening atmosphere, the patched and dusty window—through which a sunbeam, like hope, is faintly stealing—the ragged, hunger-bitten and sad-faced children, the ruffian man, the heap of straw where some wretched mother in muttering dreams sleeps off last night's debauch or lies unshrouded and uncoffined in the ghastliness of a hopeless death, are sad scenes. We have often looked on them, and they appear all the sadder for the restless play of fancy excited by some vestiges of a fresco-painting that still looks out from the foul and broken plaster, the massive marble rising over the cold and cracked hearthstone, an elaborately-carved cornice too high for shivering cold to pull it down for fuel, some stucco flowers or fruit yet pendent on the crumbling ceiling. Fancy, kindled by these, calls up the gay scenes and actors of other days, when beauty, elegance and fashion graced these lonely halls, and plenty smoked on groaning tables, and where these few cinders, gathered from the city dustheap, are feebly smouldering, hospitable fires roared up the chimney."

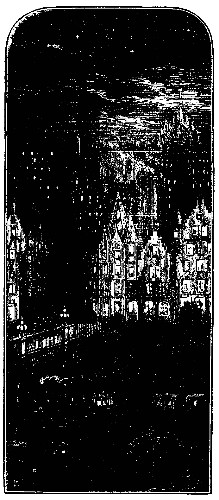

OLD EDINBURGH BY NIGHT.

OLD EDINBURGH BY NIGHT.

These houses are built upon the "flat" system, some of the better ones having a court in the centre like French houses, and turrets at the corners for the circular staircases connecting the different flats. Fires and improvements are rapidly sweeping them away, and the traveler regrets or not their disappearance, according as his views may be sentimental or sanitarian. They are truly ill adapted to modern ideas of hygiene, or to those cunning modern devices which sometimes poison their very inventors. While we may smile at our ancestors' free and easy way of pitching things out of the window, we should at least remember that they knew nothing of the modern plague of sewer-gas stealing its insidious way into the apparently best-regulated households. But without entering upon the vexed question of hygiene, the fact is that where there is no reason for propping up a tottering roof except that it once sheltered some bloody, cattle-stealing chieftain of the Border, utilitarian sentiments carry the day; nor ought any enthusiast to deny that the heart-shaped figure on the High street[Pg 30] pavement, marking the spot where the Heart of Mid Lothian once stood, is a more cheerful sight than would be presented by the foul walls of that romantic jail.

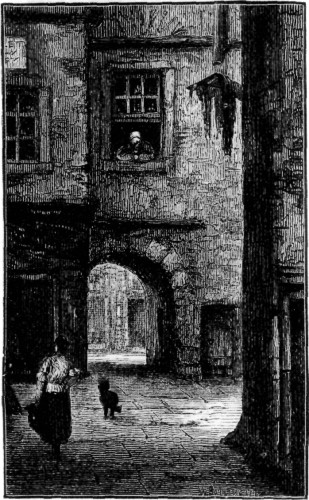

RIDDLE'S CLOSE, WHERE HUME COMMENCED HIS "HISTORY OF

ENGLAND."

RIDDLE'S CLOSE, WHERE HUME COMMENCED HIS "HISTORY OF

ENGLAND."

The modes of life in old Edinburgh have been amply illustrated by many writers. Among the novel-writers, Scott and Miss Ferrier have especially dwelt upon them. The tavern-haunting habits of the gentlemen are pleasantly depicted in the "high jinks" in Guy Mannering, and the depth of potations may be estimated by Burns's "Song of the Whistle." As to the ladies, we should not have found their assemblies very hilarious, where partners for the dance were obtained by drawing tickets, and the lucky or unlucky swain danced one solemn minuet with his lady, and was not expected to quit her side during the evening—

The huge stack of buildings called James's Court is associated with the names of Boswell and of Hume. Half of it has been destroyed by fire, and precisely that half in which these two worthies once dwelt, but there is quite enough of it left to show what a grim monster it was, and, for that matter, still is. In Boswell's time it was a fine thing to have a flat in James's Court. Here Boswell was living when Dr. Johnson came to visit him. Boswell, having received a note from Johnson announcing his arrival, hastened to the inn, where he found the great man had just thrown his lemonade out of the window, and had nearly knocked down the waiter for sweetening the said lemonade without the aid of the sugar-tongs.

"Mr. Johnson and I walked arm-in-arm up the High street," says Boswell, "to my house in James's Court: it was a dusky night: I could not prevent his being assailed by the evening effluvia of Edinburgh. As we marched slowly along he grumbled in my ear, 'I smell you in the dark.'"

Mrs. Boswell had never seen Johnson before, and was by no means charmed with him, as Johnson was not slow to discover. In a matrimonial aside she whispered to her husband, "I have seen many a bear led by a man, but I never before saw a man led by a bear." No doubt her provocations were great, and she wins the compassionate sympathy of all good housekeepers when they read of Ursa Major brightening up the candles by turning the melted wax out on the carpet.

Many years after this, but while Boswell was still living in James's Court, a lad named Francis Jeffrey one night helped to carry the great biographer home—a circumstance in the life of a gentleman much more of an every-day or every-night affair at that time than at present. The next day Boswell patted the lad on the head, and kindly added, "If you go on as you have begun, you may live to be a Bozzy yourself yet."

The stranger who enters what is apparently the ground-floor of one of these houses on the north side of High street is often surprised to find himself, without having gone up stairs, looking from a fourth-story window in the rear. This is[Pg 31] due to the steep slope on which the houses stand, and gives them the command of a beautiful view, including the New Town, and extending across the Firth of Forth to the varied shores of Fife. From his flat in James's Court we find David Hume, after his return from France, writing to Adam Smith, then busy at Kirkcaldy about the Wealth of Nations, "I am glad to have come within sight of you, and to have a view of Kirkcaldy from my windows."

Another feature of these houses is the little cells designed for oratories or praying-closets, to which the master of the house was supposed to retire for his devotions, in literal accordance with the gospel injunction. David Hume's flat had two of these, for the spiritual was relatively better cared for than the temporal in those days: plenty of praying-closets, but no drains! This difficulty was got over by making it lawful for householders, after ten o'clock at night, to throw superfluous material out of the window—a cheerful outlook for Boswell and others being "carried home"!

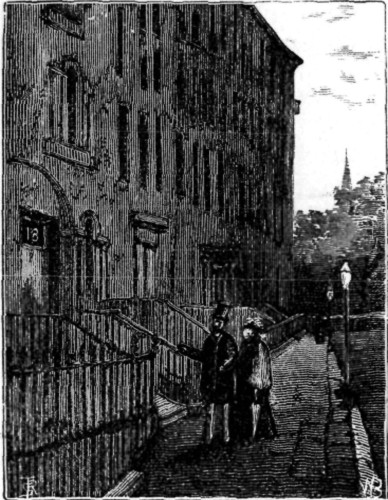

BUCCLEUGH PLACE, WHERE THE "EDINBURGH REVIEW" WAS

PROJECTED.

BUCCLEUGH PLACE, WHERE THE "EDINBURGH REVIEW" WAS

PROJECTED.

COLLEGE WYND, WHERE SCOTT WAS BORN.

COLLEGE WYND, WHERE SCOTT WAS BORN.

At the bottom of Byre's Close a house is pointed out where Oliver Cromwell stayed, and had the advantage of contemplating from its lofty roof the fleet which awaited his orders in the Forth. The same house was once occupied by Bothwell, bishop of Orkney, and is associated with the memory of Anne, the bishop's daughter, whose sorrows are enbalmed in plaintive beauty in the old cradle-song:

ANCHOR CLOSE.

ANCHOR CLOSE.

The tourist finds much to read, as he runs through old Edinburgh, in the mottoes on the house-fronts. These are mostly of a scriptural and devout character, such as: "Blissit.Be.God.In.Al.His.Giftis;" or, "Blissit.Be.The.Lord.In.His.Giftis.For.Nov.And.Ever." If he peeps into Anchor Close, where once was a famous tavern, he will find it entirely occupied by the buildings of the Scotsman newspaper, but the mottoes have been carefully preserved and built into the walls. The first is, "The.Lord. Is.Only.My.Svport;" a little farther on, "O.Lord.In.The.Is.Al.My.Traist;" and over the door, "Lord.Be.Merciful.To.Me." On other houses he may read, "Feare.The.Lord.And.Depart.From.Evill;" "Faith.In.Chryst.Onlie.Savit;" "My.Hoip.Is.Chryst;" "What.Ever.Me.Befall.I.Thank.The.Lord.Of.All." There are also many in the Latin tongue, such as, "Lavs Vbique Deo;" "Nisi Dominvs Frvstra" (the City motto);

Here is one in the vernacular: "Gif.Ve.Died.As.Ve.Sovld.Ve.Mycht.Haif.As.Ve.Vald;" which is translated, "If we did as we should, we might have as we would."

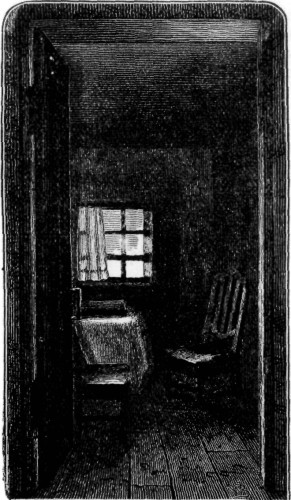

JOHN KNOX'S STUDY.

JOHN KNOX'S STUDY.

Near the end of the High street, on the way to the Canongate, stands John Knox's house, which has been put in order and made a show-place. The exterior, from its exceedingly picturesque character, is more attractive than the interior. The house had originally belonged to the abbot of Dunfermline, and when taken by Knox a very snug little study was added, built of wood and projecting from the front, in accordance with an order from the magistrates, directing "with al diligence to make ane warm studye of dailles to the minister John Knox, within his hous, aboue the hall[Pg 33] of the same, with light and wyndokis thereunto, and al uther necessaris." The motto of this house is "Lvfe.God.Abvfe.Al.And.Yi.Nychtbovr.As.Yi.Self." A curious image at one corner was long thought to represent Knox preaching, and probably still does so in the popular belief; but others now think it represents Moses. It is an old man kneeling, with one hand resting on a tablet, and with the other pointing up to a stone above him carved to resemble the sun, and having on its disk the name of the Deity in three languages: "ΘΕΟΣ.Deus.God."

Of the style of Knox's preaching, even when he was enfeebled by ill-health, one gets a good idea from the following passage in James Melville's diary: "And by the said Rickart and an other servant, lifted up to the pulpit whar he behovit to lean, at his first entrie; bot or he had done with his sermon, he was sa active and vigorous, that he was lyk to ding that pulpit in blads and flie out of it."

ROOM IN WHICH KNOX DIED.

ROOM IN WHICH KNOX DIED.

Passing on down Canongate, once the court suburb, we come to Moray House, the former residence of the earls of Moray, and at one time occupied by Cromwell. It is now used for a school, and is in much better preservation than many of its neighbors. At the very bottom of the Canongate, not far from Holyrood House, stands the White Horse Inn. The house has not been an inn for many years, but was chosen by Scott as the quarters of Captain Waverley: its builders probably thought little of beauty when they built it, yet squalor, dilapidation and decay have given it the elements of the picturesque, and the fact that Scott has mentioned it is sufficient to nerve the tourist to hold his nose and admire.

A black, gaunt, forbidding-looking structure near at hand was once the residence of the dukes of Queensberry. Charles, the third duke, was born in it: it is his duchess, Lady Catherine Hyde, whose pranks are so frequently recorded in Horace Walpole's letters—"very clever, very whimsical, and just not mad." Their Graces did not often occupy their Scottish residences, but in 1729, the lord chamberlain having refused his license to Gay's play, Polly, a continuation of the Beggar's Opera, the duke and duchess took Gay's part so warmly as to leave the court and retire to Queensberry House, bringing the poet with them.[Pg 34]

WHITE HORSE INN.

WHITE HORSE INN.

The duchess was much sung by the poets of her day, among them Prior, who is now so little read that we may recall a few of his once well-known verses:

On the death of Duke Charles, Queensberry House came into the possession of his cousin, the earl of March, a singular man-about-town in London, known as "Old Q.:" he stripped it of all its ornaments, without and within, and sold it to the government for a barracks. It is now used as a house of refuge. On its gate are the following notices: "White-seam sewing neatly executed." "Applications for admission by the destitute any lawful day from 10 to 12." "Bread and soup supplied from 1 to 3, afternoon. Porridge supplied from 8 to 9, morning, 6 to 7, evening." "Night Refuge open at 7 P.M. No admission on Sundays." "No person allowed more than three nights' shelter in one month." Such are the mottoes that now adorn the house which sheltered Prior's Kitty.

A striking object in the same vicinity is the Canongate Tolbooth, with pepper-box turrets and a clock projecting from the front on iron brackets, which have taken the place of the original curiously-carved oaken beams. Executions sometimes took place in front of this building, which led wags to find a grim joke in its motto: "Sic.Itvr.Ad.Astra." A more frequent place of execution was the Girth Cross, near the foot of the Canongate, which marked the limit of the right of sanctuary belonging to the abbey of Holyrood. At the Girth Cross, Lady Warriston was executed for the murder of her husband, which has been made the subject of many ballads:

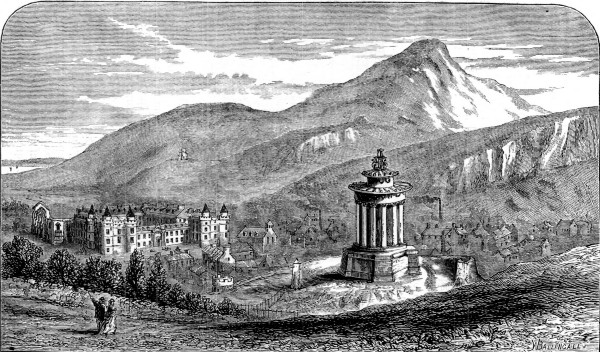

HOLYROOD AND BURNS'S MONUMENT.

HOLYROOD AND BURNS'S MONUMENT.

Another version has:

The murder was committed on the 2d of July, 1600, and with the speedy justice of that time the punishment followed on the 5th. The lady was sentenced to be "wooried at the stake and brint," but her relatives had influence enough to secure a modification of the sentence, so that she was beheaded by the "maiden," a form of guillotine introduced by the Regent Morton. The original sentence was executed upon the nurse, who had no powerful relatives.

STONE ON WHICH THE COVENANT WAS SIGNED.

STONE ON WHICH THE COVENANT WAS SIGNED.

Directly opposite the Canongate Tolbooth is a very antiquated dwelling, with three gables to the street, which converses with the passer-by on envy and backbiting. It begins: "Hodie.Mihi.Cras.Tibi.Cur.Igitur.Curas" ("To-day, mine; to-morrow, thine; why then care?"). As if premising an unsatisfactory answer, it continues: "Ut Tu Linguae Tuae, Sic Ego Mear. Aurium, Dominus Sum." ("As thou of thy tongue, so I of my ears, am lord"), and finally takes refuge in "Constanti Pectori Res Mortalium Umbra" ("To the steadfast heart the affairs of mortals are but shadows").

In the plain at the foot of the Canongate stands Holyrood Abbey and Palace, which, with the exception of one wing containing Queen Mary's apartments, has been rebuilt within comparatively modern times. The abbey church is a crumbling ruin, although a power amid its decay, for it possesses still the right of sanctuary. This refuge offered by the Church was a softening and humanizing influence when private feuds were settled by the sword and the Far-West principle of death at sight generally prevailed: later on, it became an abuse, and gradually disappeared. The Holyrood sanctuary is the only one now existing in Great Britain, but is available for insolvent debtors only: it includes the precincts of the palace and the Queen's Park (five miles in circumference), but it contains no buildings except in that portion of the precincts extending from the palace to the foot of Canongate, about one hundred and thirty yards in a direct line. Within this limited district the debtor seeks his lodging, has the Queen's Park for his recreation, and on Sundays is free to go where he likes, as on that day he cannot be molested. It was a curious relic of old customs to read in Edinburgh newspapers in the year 1876 the following extract from a debtor's letter, in which he makes his terms with the sheriff: "However desirous I am to obey the order of the sheriff to attend my examination, I am sorry to be obliged to intimate that in consequence of the vindictive and oppressive proceedings of some of my creditors I cannot present myself in court at the diet fixed unless protection from personal diligence be granted. I will have much pleasure, however, in attending the court in the event of the sheriff granting a special warrant to bring me from the sanctuary, which warrant shall protect me against arrest for debt and other civil obligations while under examination, and on the way to and from the place of examination." The sheriff granted the warrant.

From Holyrood we fancy the traveler next remounting the hill into the Old Town, and seeking out the churchyard[Pg 37] of Greyfriars, whose monuments, full of interest to the student and the antiquary, are in themselves an epitome of Scottish history. The church has been ravaged by fire and rebuilt, so that it retains but little antiquity: the churchyard, on the other hand, has seen few changes except in the increase of its monuments as time has passed on.

Here the Solemn League and Covenant was entered into. It was first read in the church, and agreed to by all there, and then handed to the crowd without, who signed it on the flat tombstones.

Among the most conspicuous monuments in this churchyard are, on the one hand, that to those who died for their fidelity to this Covenant, and on the other the tomb of Sir George Mackenzie, king's advocate and public prosecutor of the Covenanters.

On the Martyrs' Monument, as it is called, one reads: "From May 27th, 1661, that the most noble marquis of Argyle was beheaded, until Feb. 18th, 1688, there were executed in Edinburgh about one hundred noblemen, gentlemen, ministers and others: the most of them lie here.

And so on.

Dr. Thomas Guthrie, who, as we have seen, found much inspiration in the scenes of his daily walks, sought to trace his origin back to this Guthrie of the Martyrs' Monument. "I failed," he wrote, "yet am conscious that the idea and probability of this has had a happy influence on my public life, in determining me to contend and suffer, if need be, for the rights of Christ's crown and the liberties of His Church."

The learning and accomplishments of Sir George Mackenzie were forgotten amid the religious animosities of his day, and he came down to posterity as the terror of nursery-maids and a portentous bugaboo under the name of Bloody Mackenzie. It is related that the boys of the town were in the habit of gathering at nightfall about his tomb and shouting in at the keyhole,

after which they would scatter, as if they feared the tenant might take them at their word. The tomb is a handsome circular Roman temple, now much dilapidated by weather and soot, and so dark and sombre as to make it very uncanny in the gloaming, especially to one approaching it with the view of shouting "Bluidy Mackenzie" through the keyhole. This popular superstition was once turned to account by a youth under sentence of death for burglary. His friends aided him in escaping from prison, and provided him with a key to this mausoleum, where he passed six weeks in the tomb with the Bluidy Mackenzie—a situation of horror made tolerable only as a means of escape from death. Food was brought to him at night, and when the heat of pursuit was over he got to a vessel and out of the country.

MACKENZIE'S TOMB.

MACKENZIE'S TOMB.

The New Town of Edinburgh is separated from the Old Town by the ravine of the North Loch, over which are thrown the bridges by which the two towns are connected. The loch has been drained[Pg 38] and is now occupied by the Public Gardens and by the railway. The New Town is substantially the work of the last half of the past century and the first half of the present one—a period which sought everywhere except at home for its architectural models. In some of the recent improvements in the Old Town very pretty effects have been produced by copying the better features of the ancient dwellings all around them, but the grandiloquent ideas of the Georgian era could not have been content with anything so simple and homespun as this. Its ideal was the cold and pompous, and it succeeded in giving to the New-Town streets that distant and repellent air of supreme self-satisfaction which makes the houses appear to say to the curious looker-on, "Seek no farther, for in us you find the perfectly correct thing." The embodiment of this spirit may be seen in the bronze statue of George IV. by Chantrey, in George street: the artist has caught the pert strut so familiar in the portraits, at sight of which one involuntarily exclaims, "Behold the royal swell!"

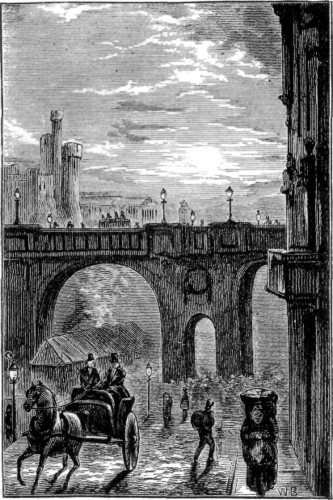

THE NORTH BRIDGE.

THE NORTH BRIDGE.

But the New Town has two superb features, about whose merits all are agreed: we need hardly say these are Princes street and the Calton Hill. Princes street extends along the brow of the hill over-hanging the ravine which separates the two towns, and which is now occupied by public gardens: along their grassy slopes the eye wanders over trees and flowers to the great rock which o'ertops the greenery, bearing aloft the Castle as its crown, while from the Castle the Old Town, clustering along the height, streams away like a dark and deeply-colored train. The Calton Hill offers to the view a wide-spreading panorama. At our feet are the smoking chimneys of Auld Reekie, from which we gladly turn our eyes to the blue water and the shores of Fife, or seek out in the shadow of Salisbury Crags and Arthur's Seat the tottering arch of Holyrood Abbey. The hill is well dotted over,

which on examination prove to be monuments to the great departed. A great change has taken place in the prevalent taste since they were erected, and they are not now pointed out to the stranger with fond pride, as in the past generation. The best one is that to Dugald Stewart, an adaptation, the guide-books say, of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates. The all-pervading photograph has made it so familiar that it comes upon one as an old friend.

The Burns Monument is a circular edifice with columns and a cupola. It has all the outward semblance of a tomb, so that one is rather startled to find it tenanted by a canny Scot—a live one—who presides with becomingly sepulchral gravity over a twopenny show of miscellaneous trumpery connected with Robert Burns. Everywhere in old Edinburgh we have seen going on the inevitable struggle between utility and sentiment: at Burns's Monument it ceases, and we conclude our ramble at this point, where the sentimentalist and the utilitarian shake hands, the former deeply sympathizing with the sentiment which led to the building of the monument, while the latter fondly admires the ingenuity which can turn even a cenotaph to account.

Alfred S. Gibbs.

[A] Baloo is a lullaby, supposed to be from the French Bas, là le loup—"Lie still, the wolf is coming."

[B] The "dear deceiver" was said to have been her cousin, the Hon. Alexander Erskine, brother to the earl of Mar. He came to a violent death, although not in the manner suggested in the ballad. While stationed at Dunglass Castle, engaged in collecting levies for the army of the Covenanters, an angry page thrust a red-hot poker into the powder-magazine, and blew him up with a number of others, so that there was "never bone nor hyre seen of them again."

On a raw, cloudy afternoon in early spring a few years ago a family-carriage was driven slowly down a lonely road in one of the outlying suburbs of Philadelphia, stopping at last in front of an apparently vacant house. This house was built of gray stone, and stood back from the road, surrounded by a few sombre pines and much rank shrubbery: shrubbery and trees, and the house itself, had long been abandoned to decay.

"Heah am de place, sah," said the footman, opening the carriage-door.

An old gentleman in shabby clothes, embellished dramatically by a red necktie, an empty sleeve pinned to his breast, sprang out briskly; a lady followed, and stood beside him: then a younger man, his head muffled in a close fur cap, a yellow shawl wrapped about his neck, looked feebly out of the window. His face, which a pair of pale, unkindled eyes had never lighted since he was born, had been incomplete of meaning in his best days, and long illness had only emphasized its weakness. He half rose, sat down again, stared uncertainly at the house, yawned nervously, quite indifferent to the fact that the lady stood waiting his pleasure. His money and his bodily sufferings—for he was weighted heavily with both—were quite enough, in his view, to give him the right to engross the common air and the service of other men and women. Indeed, a certain indomitable conceit thrust itself into view in his snub nose and retreating chin, which made it highly probable that if he had been a stout day-laborer in the road yonder, he would have been just as complacent as now, and have patronized his fellows in the ditch.

"Will you take my arm, William?" said the old man waiting in the road. "This is the house."

"No. I have half a mind to drop the whole matter. Why should I drag out the secrets of the grave? God knows, I shall find them out soon enough!"

"Just so. Precisely. It's a miserable business for this April day. Now, I don't want to advise, but shall we drive out on the Wissahickon and fish a bit? You'll catch a perch, and Jane shall broil it over the coals, eh?"

"Oh, of course I'm going through with it," scowling and blinking through his eye-glasses. "But we are ten minutes before the time. I can't sit in a draughty room waiting. Tell David to drive slowly down the road until four, Captain Swendon."

"Certainly, certainly," with the nervous conciliatory haste of a man long used to being snubbed.—"You hear Mr. Laidley, David?—We'll arrange it in this way, then. Miss Fleming and I will stroll down the road, William, until the time is up.—No, Jane," as his daughter was going to leave the carriage. "Stay with your cousin." The captain was his peremptory self again. Like every man conscious of his own inability, he asserted himself by incessant managing and meddling for his neighbors.

The carriage jolted down the rutted road. The little man inside tossed on the well-padded cushions, and moaned and puffed spasmodically at his cigar.

Buff and David, stiff in green and gold on the box, nodded significantly at each other. "He's nigh unto de end," said Buff. "De gates of glory am creakin' foh him."

"Creakin', shore nuff. But 'bout de glory I'm not so shore. Yoh see, I knows," rubbing his gray whiskers with the end of the whip. "I have him in charge. Mass' Swendon gib orders: 'Yoh stick by him, Dave.' 'S got no friends: 's got no backbone. Why, wid a twinge ob toothache he squirms like an eel in de fire—swears to make de debbil turn pale. It'll be an awful sight when Death gits a holt on him. But I'll stick."

Captain Swendon and Miss Fleming, left alone under the pines, both turned and looked at the house as if it were an open grave.[Pg 40]

"So it is here the dead are to come back?" said the captain with a feebly-jocular giggle. "We'll go down the road a bit. 'Pon my soul, the atmosphere here is ghastly."

They struck into the meadows, sauntered through a strip of woodland where the sparrows were chirping in the thin green boughs overhead, and, crossing some newly-ploughed fields, came suddenly upon a row of contract-houses, bold, upright in the mud, aggressively new and genteel. They were tricked out with thin marble facings and steps. A drug-shop glittered already at one end of the block, and a milliner's furbelowed window closed the other with a red-lettered sign, which might have served as a motto for the whole: "Here you buy your dollar's worth of fashion for your dime of cash."

"Ah!" cried the captain, "no ghostly work here!—the last place where one would look for any miraculous stoppage of the laws of Nature."

"Stoppage, you should say, of the social laws of 'gents' and their ladies, which are much more inexorable," said his companion. "Oh I know them!" glancing in at the windows, as she tramped through the yellow mud, with keen, amused eyes. "I know just what life must be in one of these houses—the starving music-teacher on one side of you, and the soapboiler on the other: the wretched small servant going the rounds of the block to whiten the steps every evening, while the mistresses sit within in cotton lace and sleazy silks, tinkling on the piano, or counting up the greasy passbook from the grocer's. Imagine such a life broken in upon by a soul from the other world!"

"Yet souls go out from it into the other world. And I've known good women who wore cheap finery and aped gentility. Of course," with a sudden gusty energy, "I don't endorse that sort of thing; and I don't believe the dead will come back to-day. Don't mistake me," shaking his head. The captain was always gusty and emphatic. His high-beaked, quick-glancing face and owlish eyes were ready to punctuate other men's thoughts with an incessant exclamation-point to bring out their true meaning. Since he was a boy he had known that he was born a drill-sergeant and the rest of mankind raw recruits. "Now, there's something terribly pathetic to me," he said, "in this whole expedition of ours. The idea of poor Will in his last days trying to catch a glimpse of the country to which he is going!"

Cornelia Fleming nodded, and let the subject drop. She never wasted her time by peering into death or religion. She belonged to this world, and she knew it. A wise racer keeps to the course for which he has been trained, and never ventures into the quagmires beyond. She stopped beside a tiny yard where a magnolia tree spread its bare stalks and dull white flowers over the fence, and stood on tiptoe to break a bud. The owner of the house, an old man with a box of carpenter's tools in his hand, opened the door at the moment. She nodded brightly to him. "I am robbing you, sir. For a sick friend yonder," she said.

He came down quickly and loaded her with flowers, thinking he had never heard a voice as peculiar and pleasant. The captain, a little behind, eyed her critically from head to foot, his mouth drawn up for a meditative whistle, as she stood on tiptoe, her arm stretched up among the creamy buds. The loose sleeve fell back: the arm was round and white.

"Very good! ve-ry good!" the whistle meant; "and I know the points of a fine woman as well as any of these young fellows."

Two young fellows, coming up, lingered to glance at the jimp waist and finely-turned ankle, with a shrug to each other when, passing by, they saw her homely face.

The captain gallantly relieved her of her flowers, and paraded down the road, head up, elbows well out, as he used, thirty years ago, to escort pretty Virginie Morôt in the French quartier of New Orleans. It was long since he had relished conversation as he did with this frank, generous creature. No coquetry[Pg 41] about her! It was like talking to a clever, candid boy. Every man felt, in fact, with Cornelia, that she was only a younger brother. He liked the hearty grasp of her big white hand; he liked her honest, downright way of stating things, and her perfect indifference to her own undeniable ugliness. Now, any other woman of her age—thirty, eh? (with a quick critical glance)—would dye her hair: she never cared to hide the streaks of gray through the yellow. She had evidently long ago made up her mind that love and marriage were impossible for women as unprepossessing as she: she stepped freely up, therefore, to level ground with men, and struck hands and made friendships with them precisely as if she were one of themselves.

The captain quite glowed with the fervor of this friendship as he marched along talking energetically. A certain subtle instinct of kinship between them seemed to him to trench upon the supernatural: it covered every thought and taste. She had a keen wit, she grasped his finest ideas: not even Jane laughed at his jokes more heartily. She appreciated his inventive ability: he was not sure that Jane did. There were topics, too, on which he could touch with this mature companion that were caviare to Jane. It was no such mighty matter if he blurted out an oath before her, as he used to do in the army. Something, indeed, in the very presence of the light, full figure keeping step with his own, in the heavy odor of the magnolias and the steady regard of the yellowish-brown eyes, revived within him an old self which belonged to those days in the army—a self which was not the man whom his daughter knew, by any means.

They were talking at the time, as it happened, of his military experience: "I served under Scott in Mexico. Jane thinks me a hero, of course. But I confess to you that I enlisted, in the first place, to keep the wolf out of the house at home. I had spent our last dollar in manufacturing my patent scissors, and they—well, they wouldn't cut anything, unless—I used to suspect Atropos had borrowed them and meant to snip the thread for me, it was stretched so tightly just then."

She looked gravely at his empty sleeve.

The captain caught the glance, and coughed uncomfortably: "Oh, I did not lose that in the service, you understand. No such luck! Five days after I was discharged, after I had come out of every battle with a whole skin, I was on a railway-train going home. Collision: arm taken off at the elbow. If it had happened just one week earlier, I should have had a pension, and Jane—Well, Jane has had a rough time of it, Miss Fleming. But it was my luck!"

They had returned through the woods, and were in sight again of the house standing darkly among the pines. Two gentlemen, pacing up and down the solitary road, came down the hill to meet them.