The Project Gutenberg EBook of Paradise Bend, by William Patterson White This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Paradise Bend Author: William Patterson White Illustrator: Ralph Pallen Coleman Release Date: December 4, 2010 [EBook #34567] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PARADISE BEND *** Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | Tom Loudon |

| II. | At the Bar S |

| III. | Shots on Pack-Saddle |

| IV. | The Skinned Cattle |

| V. | Their Own Deceivings |

| VI. | Pestilent Fellows |

| VII. | Paradise Bend |

| VIII. | The Amazing Mackenzie |

| IX. | Authors of Confusion |

| X. | The Horse Thief |

| XI. | Rocket |

| XII. | Scotty Advises |

| XIII. | The Dance |

| XIV. | A Determined Woman |

| XV. | A Hidden Trail |

| XVI. | Kate Is Helpful |

| XVII. | Mrs. Burr Relieves Her Mind |

| XVIII. | A Murder and a Killing |

| XIX. | Marysville |

| XX. | The Railroad Corral |

| XXI. | The Judge's Office |

| XXII. | Under the Ridge |

| XXIII. | The Smoke of Conflict |

| XXIV. | Before the Dawn |

| XXV. | Trail's End |

"And don't forget that ribbon!" called Kate Saltoun from the ranch-house door. "And don't lose the sample!"

"I won't!" shouted Tom Loudon, turning in his saddle. "I'll get her just like you said! Don't you worry any!"

He waved his hat to Kate, faced about, and put his horse to a lope.

"Is it likely now I'd forget?" he muttered. "We'd do more'n that for her, wouldn't we, fellah?"

The horse, a long-legged chestnut named Ranger, turned back one ear. He was accustomed to being questioned, was Ranger. Tom Loudon loved him. He had bought him a five-year-old from the 88 ranch the year before, and he would allow no one save Kate Saltoun to ride him. For the sun and the moon, in the estimation of Tom Loudon, rose and set in the black eyes of Kate Saltoun, the exceedingly handsome daughter of John T. Saltoun, the owner of the great Bar S ranch.

This day Loudon was riding into Farewell for the ranch mail, and Kate had commissioned him to do an errand for her. To serve his lady was joy to Loudon. He did not believe that she was aware of his state of mind. A flirt was Kate, and a charming one. She played with a man as a cat plays with a mouse. At which pleasant sport Kate was an adept. But Loudon realized nothing of all this. Shrewd and penetrative in his business, where Kate was concerned he saw nothing but the obvious.

Where the trail snaked over Indian Ridge, ten miles from the ranch house, Loudon pulled up in front of a lone pine tree. On the trunk of the pine a notice was tacked. Which notice set forth briefly that two hundred dollars' reward was offered for the person or persons of the unknown miscreant or miscreants who were depleting the herds of the Bar S and the Cross-in-a-box outfits. It was signed by Sheriff Block.

Who the miscreants were no one knew with certainty. But strange tales were told of the 88 punchers. It was whispered that they carried running-irons on their saddles. Certainly they displayed, when riding the range, a marked aversion to the company of men from the other ranches.

The remains of small fires had been found time and again in draws bordering the 88 range, and once a fire-marked cinch-ring had been picked up. As the jimmy and bunch of skeleton keys in a man's pocket so are the running-iron and the extra cinch-ring under a puncher's saddle-skirts. They indicate a criminal tendency; specifically, in the latter case, a whole-hearted willingness to brand the cattle of one's neighbour.

Loudon read the notice of reward, slow contempt curling his lips.

"Signs," he said, gently. "Signs——! What we need is Vigilantes—Vigilantes an' a bale o' rope!"

He turned in his saddle and looked back over the way he had come. Fifty miles to the south the Frying Pan Mountains lay in a cool, blue, tumbling line.

From where Loudon sat on his horse to the Frying Pans stretched the rolling range, cut by a thin, kinked strip of cottonwoods marking the course of a wandering river, pockmarked with draws and shallow basins, blotched with clumps of pine and tamarack, and humped with knolls and sprawling hills. The meandering stream was the Lazy, and all the land in sight, and beyond for that matter, was the famous Lazy River country held by three great ranches, the Cross-in-a-box, the Bar S, and the 88.

Of these the 88 was the largest and the farthest west of the three, its eastern line running along the high-bluffed banks of the Falling Horse, which emptied into the Lazy some ten miles from the 88 ranch house. East of the 88 lay the Bar S, and east of the Bar S was the Cross-in-a-box. The two latter ranches owned the better grazing, the more broken country lying within the borders of the 88 ranch.

Beyond the 88 range, across the Falling Horse, were the Three Sisters Mountains, a wild and jumbled tangle of peaks and narrow valleys where the hunter and the bear and the mountain lion lived and had their beings. East of the Lazy River country lay the Double Diamond A and the Hog-pen outfits; north and south stretched other ranches, but all the ranges ended where the Three Sisters began.

Loudon swung his gaze westward, then slowly his eyes slid around and fastened on the little brown dots that were the ranch buildings of the Bar S. He shook his head gently and sighed helplessly.

He was thinking partly of Kate and partly of her father, the gray old man who owned the Bar S and would believe nothing evil of his neighbours, the hard-riding 88 boys. Loudon was morally certain that forty cows within the last three months had transferred their allegiance from Bar S to 88, and he had hinted as much to Mr. Saltoun. But the latter had laughed him to scorn and insisted that only a few cows had been taken and that the lifting was the work of independent rustlers, or perhaps of one of the other ranches. Nevertheless, in response to the repeated urging of his foreman, Bill Rainey, Mr. Saltoun had joined with the Cross-in-a-box in offering a reward for the rustlers.

Loudon was well aware of the reason for Mr. Saltoun's fatuous blindness. That reason was Sam Blakely, the 88 manager, who came often to the Bar S ranch and spent many hours in the company of Kate. Mr. Saltoun did not believe that a dog would bite the hand that fed him. But it all depends on the breed of dog. And Blakely was the wrong breed.

"He shore is a pup," Loudon said, softly, "an' yellow at that. He'd steal the moccasins off a dead Injun. An' Block would help him, the cow-thief."

Then, being young, Loudon practised the road-agent's spin on the notice of reward tacked on the pine tree, and planted three accurate bullets in the same spot.

"Here, you! What yuh doin'?" rasped a grating voice in Loudon's immediate rear.

Loudon turned an unhurried head. Ten yards distant a tall man, black-bearded, of a disagreeable cast of countenance, was leaning forward across an outcrop.

"I asked yuh what yuh was doin'?" repeated the peevish individual, glaring at Loudon.

"I heard yuh the first time, Sheriff," replied Loudon, placidly. "I was just figurin' whether to tell yuh I was shoein' a horse or catchin' butterflies. Which answer would yuh like best?"

"Yuh think yo're mighty funny, Tom Loudon, but I tell yuh flat if yuh don't go slow 'round here I'll find a quick way o' knockin' yore horns off."

"Yuh don't say. When yuh goin' to begin?"

Loudon beamed upon the sheriff, his gun held with studied carelessness. Sheriff Block walked from behind his breastwork, his eyes watchful, his thumbs carefully hooked in the armholes of his vest.

"That notice ain't no target," he grunted, halting beside the pine tree.

"It is now," remarked Loudon, genially.

"It won't be no more."

"O' course not, Sheriff. I wouldn't think o' shootin' at it if you say no. It's a right pretty piece o' readin'. Did yuh write it all yoreself?"

The sheriff's eyes became suddenly blank and fixed. His right thumb slowly unhooked.

"I only fired three shots," observed Loudon, the muzzle of his six-shooter bearing on the pit of the sheriff's stomach.

The sheriff's right thumb rehooked itself hurriedly. His frame relaxed.

"Yuh shouldn't get mad over a joke," continued Loudon. "It's plumb foolish. Been hidin' behind that rock long?"

"I wasn't hidin' behind it. I was down in the draw, an' I seen you a-readin' the notice, an' I come up."

Loudon's gray eyes twinkled. He knew that the sheriff lied. He knew that Block had heard his comments on Blakely and his own worshipful person, but evidently the sheriff did not consider this an opportune time for taking umbrage.

"So yuh come up, did yuh? Guess yuh thought it was one o' the rustlers driftin' in to see what reward was out for him, didn't yuh? But don't get downhearted. Maybe one'll come siftin' along yet. Why don't yuh camp here, Sheriff? It'll be easier than ridin' the range for 'em, an' a heap healthier. Now, Sheriff, remember what I said about gettin' red-headed. Say, between friends, an' I won't tell even the little hoss, who do you guess is doin' the rustlin'?"

"If I knowed," growled the sheriff, "his name'd be wrote on the notice."

"Would it? I was just wonderin'. Habit I got."

"Don't you fret none about them rustlers. I'll get 'em if it takes ten years."

"Make it twenty, Sheriff. They'll keep right on electin' yuh."

"Do yuh mean to say the rustlers elected me?" exploded the sheriff.

"O' course not," chided Loudon, gently. "Now what made yuh think I meant that?"

"Well, yuh said——" began the sheriff.

"I said 'they,'" interrupted Loudon. "You said 'rustlers'. Stay in the saddle, Sheriff. You'll stub your toe sometime if yuh keep on a-travellin' one jump ahead o' the hoss."

"Yo're —— smart for a cow-punch."

"It is a cinch to fool most of 'em, ain't it—especially when yo're a sheriff?"

Loudon's eyes were wide open and child-like in their gray blandness. But the sheriff did not mistake his man. Block knew that if his hand dropped, a bullet would neatly perforate his abdomen. The sheriff was not a coward, but he had sense enough not to force an issue. He could afford to wait.

"I'll see yuh again," said the sheriff, harshly, and strode diagonally down the slope.

Loudon watched him until he vanished among the pines a hundred yards below. Then Loudon touched his horse with the spur and rode on, chin on shoulder, hands busy reloading his six-shooter. Three minutes later Loudon saw the sheriff, mounted on his big black stallion, issue from the wood. The great horse scrambled up the hillside, gained the trail, and headed south.

"Bet he's goin' to the 88," said Loudon. "I'd give ten dollars to know what Block was roostin' behind that rock for. Gawd! I shore would admire to be Sheriff o' Fort Creek County for thirty days!"

Eleven miles from Indian Ridge he topped a rise and saw below him Farewell's straggly street, flanked by several false-fronted saloons, two stores, one hotel leaning slightly askew, and a few unkempt houses, the whole encircled by the twinkling pickets of innumerable bottles and tin cans.

He rode along the street, fetlock-deep in dust, and stopped at the hotel corral. Freeing Ranger of the saddle and bridle, he opened the gate and slapped the chestnut on the hip.

"Go on in, fellah," said Loudon. "Yore dinner's a-comin'."

He walked around to the front of the hotel. Under the wooden awning a beefy, red-faced citizen was dozing in a chair tilted back against the wall. Loudon tapped the snoring individual on the shoulder. The sleeper awoke gaspingly, his eyes winking. The chair settled on four legs with a crash.

"Howdy, Bill," said Loudon, gravely.

"Howdy, Tom," gurgled the other.

"Hoss in the corral an' me here, Bill. Feeds for two."

"Sure. We've done et, but you go in an' holler for Lize. She'll fix you up."

The fat landlord waddled stableward and Loudon entered the hotel. A partition that did not reach the ceiling divided the sleeping apartments from the dining room. Carelessly hanging over the partition were two shirts and someone's chaps.

The whole floor slanted, for, as has been said, the hotel leaned sidewise. The long table in the dining room, covered with cracked and scaling oilcloth, was held unsteadily upright by three legs and a cracker box.

Loudon, quite untouched by this scene of shiftlessness, hooked out a chair with his foot, dropped his hat on the floor, and sat down.

"Oh, Mis' Lainey!" he called.

A female voice, somewhat softened by distance and a closed door, instantly began to make oration to the effect that if any lazy chunker of a puncher thought he was to eat any food he was very much mistaken.

The door banged open. A slatternly, scrawny woman appeared in the doorway. She was still talking. But the clacking tongue changed its tone abruptly.

"Oh, it's you, Tom Loudon!" exclaimed the lean woman. "How are yuh, anyway? I'm shore glad to see yuh. I thought yuh was one o' them rousy fellers, an' I wouldn't rustle no more chuck this noon for the likes o' them, not if they was starvin' an' their tongues was hangin' out a foot. But yo're different, an' I ain't never forgot the time you rode thirty mile for a doc when my young one was due to cash. No, you bet I ain't! Now don't you say nothin'. You jest set right patient a short spell an' I'll rustle——"

The door swung shut, and the remainder of the sentence was lost in a muffled din of pans. Loudon winked at the closed door and grinned.

He had known the waspish Mrs. Lainey and her paunchy husband since that day when, newly come to the Lazy River country, he had met them, their buckboard wrecked by a runaway and their one child apparently dying of internal injuries. Though Loudon always minimized what he had done, Mrs. Lainey and her husband did not. And they were not folk whose memories are short.

In less than twenty minutes Mrs. Lainey brought in a steak, fried potatoes, and coffee. The steak was fairly tough, so were the potatoes, and the coffee required a copious quantity of condensed milk to render it drinkable. But Loudon ate with a rider's appetite. Mrs. Lainey, arms folded in her apron, leaned against the doorjamb, and regaled him with the news of Farewell.

"Injun Joe got drunk las' week an' tried to hogtie Riley's bear. It wasn't hardly worth while buryin' Joe, but they done it. Mis' Stonestreet has a new baby. This one makes the twelfth. Yep, day before yestiddy. Charley's so proud over it he ain't been sober since. Slep' in the waterin'-trough las' night, so he did, an' this mornin' he was drunk as ever. But he never did do things by halves, that Charley Stonestreet. Ain't the heat awful? Yep, it's worse'n that. Did yuh hear about——"

Poor, good-hearted Mrs. Lainey. With her, speech was a disease. Loudon ate as hurriedly as he could, and fled to the sidewalk. Bill Lainey, who had fallen asleep again, roused sufficiently to accept six bits.

"Mighty drowsy weather, Tom," he mumbled.

"It must be," said Loudon. "So long."

Leaving the sleepy Lainey to resume his favourite occupation, Loudon walked away. Save Lainey, no human beings were visible on the glaring street. In front of the Palace Saloon two cow-ponies drooped. Near the postoffice stood another, bearing on its hip the Cross-in-a-box brand.

From the door of the postoffice issued the loud and cheerful tones of a voice whose owner was well pleased with the world at large.

"Guess I'll get that ribbon first," said Loudon to himself, and promptly walked behind the postoffice.

He had recognized the cheerful voice. It was that of his friend, Johnny Ramsay, who punched cows for the Cross-in-a-box outfit. And not for a month's pay would Loudon have had Johnny Ramsay see him purchasing yards of red ribbon. Ramsay's sense of humour was too well developed.

When four houses intervened between himself and the postoffice Loudon returned to the street and entered the Blue Pigeon Store. Compared with most Western frontier stores the Blue Pigeon was compactly neat. A broad counter fenced off three sides of the store proper.

Behind the counter lines of packed shelves lined the walls from floor to ceiling. Between the counter and the shelves knotted ropes, a long arm's-length apart, depended from the rafters. Above the canvas-curtained doorway in the rear hung the model of a black-hulled, slim-sparred clipper.

At the jingle of Loudon's spurs on the floor the canvas curtain was pushed aside, and the proprietor shuffled and thumped, for his left leg was of wood, into the store. He was a red-headed man, was Mike Flynn, the proprietor, barrel-chested, hairy-armed, and even the backs of his ham-like hands were tattooed.

"Good aft'noon to yuh, Tom," said Mike Flynn. "'Tis a fine day—hot, mabbe, but I've seen worse in the Horse Latitudes. An' what is it the day?"

"Red ribbon, Mike," replied Loudon, devoutly thankful that no other customer was in the store.

Mike glanced at the sample in Tom Loudon's hand.

"Shore, an' I have that same, width an' all," he said, and forthwith seizing one of the knotted ropes he pulled himself hand over hand to the top shelf.

Hanging by one hand he fumbled a moment, then lowered himself to the floor.

"An' here yuh are!" he exclaimed. "The finest ribbon that ever come West. Matches the bit yuh have like a twin brother. One dollar two bits a yard."

"I'll take five yards."

"Won't yuh be needin' a new necktie now?" inquired Mike Flynn, expertly measuring off the ribbon. "I've a fine lot in—grane ones, an' blue ones, an' purple ones wit' white spots, an' some black ones wit' red an' yaller figgers, not to spake o' some yaller ones wit' vi'let horseshoes. Very fancy, thim last. God be with the ould days! Time was when I'd not have touched yaller save wit' me foot, but 'tis so long since I've hove a brick at an Orangeman that the ould feelin' ain't near so strong as it was. An' here's the ribbon, Tom. About them neckties now. They're worth seein'. One minute an' I'll delight yore eyes."

Rapidly Mike Flynn stumped around to the other side of the room, pulled down several long boxes and deftly laid them, covers off, on the counter. Loudon did need a new necktie. What man in love does not? He passed over the yellow ones with violet horseshoes so strongly recommended by Mike Flynn, and bought one of green silk.

"Yo're a lad after me own heart, Tom Loudon," said Mike Flynn, wrapping the necktie. "Grane's best when all's said an' done. The colour of ould Ireland, God bless her. An' here comes Johnny Ramsay."

Loudon hastily stuffed his purchases inside his flannel shirt, and in a careless tone asked for a box of forty-five calibre cartridges. He turned just in time to ward off the wild rush of Johnny Ramsay, who endeavoured to seize him by the belt and waltz him round the store.

"Wow! Wow!" yelled Johnny. "How's Tommy? How's the boy? Allemane left, you old bronc buster!"

"Quit it, you idjit!" bawled Loudon, the crushing of ribbon and necktie being imminent.

Ramsay stepped back and prodded Loudon's breast with an inquiring finger.

"Paddin'," he said, solemnly. "Tryin' to give yoreself a chest, ain't yuh, you old bean-pole? Ouch!"

For Loudon had dug a hard knuckle into his friend's left side, and it was Ramsay's turn to yell. From behind the counter Mike Flynn beamed upon them. He liked them well, these careless youngsters of the range, and their antics were a source of never-ending amusement.

Entered then a tall, lean man with black hair, and a face the good looks of which were somewhat marred by a thin-lipped mouth and sharp, sinister eyes. But for all that Sam Blakely, the manager of the 88 ranch, was a very handsome man. He nodded to the three, his lips parting over white teeth, and asked Mike Flynn for a rope.

"Here's yore cartridges, Tom," called Mike, and turned to the rear of the store.

Loudon picked up his box of cartridges, stuffing them into a pocket in his chaps.

"Let's irrigate," he said to Ramsay.

"In a minute," replied his friend. "I want some cartridges my own self."

The two sat down on the counter to wait. Blakely strolled across to the open boxes of neckties.

"Cravats," he sneered, fingering them.

"An' —— fine ones!" exclaimed Mike Flynn, slamming down the coil of rope on the counter. "Thim yaller ones wit' vi'let spots now, yuh couldn't beat 'em in New York. An' the grand grane ones. Ain't they the little beauts? I just sold one to Tom Loudon."

"Green shore does suit some people," said the 88 manager, coldly.

Loudon felt Johnny Ramsay stiffen beside him. But Loudon merely smiled a slow, pleasant smile.

"Hirin' any new men, Sam?" he inquired, softly, his right hand cuddling close to his belt.

"What do yuh want to know for?" demanded Blakely, wheeling.

"Why, yuh see, I was thinkin' o' quittin' the Bar S, an' I'd sort o' like to get with a good, progressive outfit, one that don't miss any chances."

Loudon's voice was clear and incisive. Each word fell with the precision of a pebble falling into a well. Mike Flynn backed swiftly out of range.

"What do yuh mean by that?" demanded Blakely, his gaze level.

"What I said," replied Loudon, staring into the other's sinister black eyes. "I shore do hate to translate my words."

For a long minute the two men gazed steadily at each other. Neither made a move. Blakely's hand hung at his side. Loudon's hand had not yet touched his gun-butt. But Blakely could not know that, for Loudon's crossed knees concealed the position of his hand.

Loudon was giving Blakely an even chance. He knew that Blakely was quick on the draw, but he believed that he himself was quicker. Blakely evidently thought, so too, for suddenly he grunted and turned his back on Loudon.

"What's that?" inquired Blakely, pointing a finger at one end of the rope.

"What—oh, that!" exclaimed Mike. "Sure, that's what a seaman calls whippin'. The holdfast was missin', an' the rope was beginning' to unlay, so I whipped the end of it. 'Twill keep the rope from frayin' out, do yuh mind. An' it's the last rope I have in stock, too."

Loudon, watching Blakely's hands, saw that what Mike Flynn called whipping was whip-cord lapped tightly a dozen turns or so round the end of the rope. Blakely, without another word, paid for the rope, picked it up, and departed, head high, sublimely indifferent to the presence of Loudon. Mike Flynn heaved a heartfelt sigh of relief.

"Praise be!" he ejaculated. "I'd thought to lose a customer a minute back." Then, recollecting himself, he added quickly, "What was that yuh said about cartridges, Johnny?"

"That's a good-lookin' goat," observed cheerful Johnny Ramsay, watching Loudon throw the saddle on the long-legged chestnut. "All he needs is horns an' a maa-a-a."

"What particular tune can you play on it?" retorted Loudon, passing the cinch-strap.

"On what?" inquired Ramsay, incautiously.

"On that four-legged accordeon yo're straddlin'."

"I wouldn't say nothin' about no accordeons—not if I was abusin' a poor billy by cinchin' a hull on his back. Honest, Tommy, don't yuh like ridin' a hoss? 'Fraid he'll throw yuh or somethin'?"

"Don't yuh worry none about this little cayuse. He's all hoss, he is, an' if yuh don't mind, Johnny, I'd be a heap obliged if yuh'd follow behind when we ride out o' town. Somebody might see us together an' take yuh for a friend o' mine, an' that wouldn't do nohow."

"Please, mister," whined Johnny Ramsay, "let me go with yuh. I know where there's a pile o' nice tomatter cans for the goat's supper. Red Rose tomatter cans, too. There's more nourishment in them kind than there is in the Blue Star brand. Hey, quit!"

Loudon had suddenly flipped a broken horseshoe at the hindquarters of Ramsay's pony, that surprised animal going into the air immediately. When Ramsay had quieted his wild-eyed mount, the two friends rode away together.

"I wonder why Blakely didn't go to it," remarked Ramsay, when Farewell lay behind them.

"Dunno," said Loudon. "He wasn't afraid, yuh can gamble on that."

"I ain't none so shore. He's bad plumb through, Blakely is. An' he's a killer, by his eyes. I guess it was just the extra shade he wanted, an' the extra shade wasn't there. You'd 'a' got him, Tom."

"Shore! But don't yuh make no mistake about Blakely bein' a coward. He ain't. He's seen trouble, an' seen it in the smoke."

"You mean Skinner Jack. Well, Jack wasn't slow with a gun, but the other two was Injuns, an' they only had Winchesters, an' Blakely he had a Sharp's. So yuh can't tally the war-whoops. An' I did hear how Skinner Jack was drunk when he called Blakely a liar."

"I doubt it. Skinner could always hold his red-eye. More likely his gun caught."

"Anyway, Tommy, you'd better not go cavortin' about on the skyline too plenteous. It wouldn't bother Blakely none to bushwhack yuh."

"Oh, he wouldn't do that. He ain't the bushwhackin' kind."

"Oh, ain't he? Now just because he ain't never done nothin' like that, it don't prove he won't. He's got a killer's eyes, I tell yuh, an' drillin' yuh would tickle him to death. Yuh run a blazer on him, an' he quit cold. Other gents seen the play. He won't never forget that. He'll down yuh on the square, or what looks like an even break, if he can. But if he can't he'll down yuh anyway."

"Rustlers ramblin' over yore way any?" inquired Loudon in a meaning tone.

Johnny Ramsay struck his saddle-horn a resounding thwack with his open palm.

"If we could only get him that way!" he exclaimed. "But he's slicker'n axle-grease."

"The 88 will brand one calf too many some day. Hell's delight! What do they do with 'em? Yuh ride the range an' yuh ride the range an' yuh don't find no cows with unhealed brands. I seen twelve, though, with the 88 brand that looked like some gent had been addin' to Bar S with a runnin'-iron. But the brands was all healed up. Anyway, we've lost forty cows, an' I dunno how many calves."

"They'll turn up again."

"Shore—carryin' the 88 brand. My idea is that them rustlers brand 'em an' then hold 'em in some blind cañon over near the Fallin' Horse till the burns heal up, an' then they throw 'em loose on the range again. If the cows do drift across to the Bar S, what's the dif? They got the 88 brand."

"That sounds good. Why don't yuh take a little wander 'round the scenery near the Fallin' Horse?"

"I have; I didn't see nothin'. But they got 'em hid somewhere all right. One day I runs across Marvin, an' I had a job losin' him. He stuck to me closer'n tar all day. He was worried some, I seen that."

"Goin' back?"

"Till I find their cache, I am."

"That's another reason for makin' Blakely so friendly. He knows yuh won't stop lookin'. Ain't it the devil an' all? The measly Sheriff just squats down on his hunkers an' does nothin' while we lose cows in car-lots. An' when our cows go, we kiss 'em good-bye. They never come back—not even with their brand altered. Yuh can't change Cross-in-a-box to 88."

"With the Bar S it's a cinch. But the boss won't use another brand. Not him. He'll stick to Bar S till he ain't got a cow to run the iron on."

"Oh, it's a great system the 88 outfit are workin'! An' with Sheriff Block an' most all o' Marysville an' Farewell their friends it's a hard game to buck. Talk o' law! There ain't none in Fort Creek County."

"The only play is Vigilantes, an' it can't come to them till there's proof. We all know Blakely an' the 88 bunch are up to their hocks in this rustlin' deal, but we can't prove it."

"There's the worst o' bein' straight," complained Johnny Ramsay. "Yuh know some tinhorn is a-grabbin' all yuh own. Yo're certain shore who the gent is, but yuh can't hop out an' bust him without yuh catch him a-grabbin' or else a-wearin' yore pet pants."

"That's whatever," agreed Loudon.

Five miles out of Farewell, where the trail forked, one branch leading southeast to the Cross-in-a-box, the other to the Bar S, Loudon checked his horse.

"Keep a-goin'," said Johnny Ramsay. "I'm travellin' with you a spell. I'm kind o' sick o' that old trail. I've rode it so frequent I know all the rocks an' the cotton-woods by their first names."

Which explanation Loudon did not accept at its face value. He understood perfectly why Ramsay continued to ride with him. Ramsay believed that Blakely would endeavour to drop Loudon from ambush, and it is well known that a gentleman lying in wait for another will often stay his hand when his intended victim is accompanied. Neither Loudon nor Ramsay made any mention of the true inwardness of his thoughts. They had been friends for a long time.

Climbing the long slope of Indian Ridge, they scanned the trail warily. But nowhere did the hoofprints of Blakely's horse leave the dust of the trail. On the reverse slope of the ridge they picked up the larger hoofprints of Block's horse. Fair and plain the two sets of marks led southward.

"Wonder who the other gent was," hazarded Ramsay.

"Block," said Loudon, "I met him this mornin'. I was puttin' holes in his notice, an' he didn't like it none."

"Did he chatter much?"

"He talked a few, but nothin' to hurt."

"The tinhorn!" laughed Ramsay. "Bet he's goin' to the 88."

"It's some likely. We'll know when we reach Long Coulee."

They reached Long Coulee, where the trail to the 88 swung westward, as the sun was dropping behind the far-away peaks of the Three Sisters Mountains. Loudon slipped his feet from the stirrups and stretched luxuriously. But he did not feel luxurious.

As he had expected, Block had turned into the 88 trail, but as he had not expected Blakely had ridden straight on toward the Bar S. Which latter event was disquieting, not that Loudon feared an act of violence on the part of Blakely, but because Kate's evening would be preëmpted by his enemy.

Loudon keenly desired to talk to Kate that evening. He had a great many things to tell her, and now the coming of Blakely spoiled it all.

"The nerve o' some folks," remarked Johnny Ramsay, eying the tracks of Blakely's horse with disfavour. "Better tell old Salt to lock up the silver an' the cuckoo clock. No offence now, Tommy, but if I was you, I'd sleep in the corral to-night. Blakely might take a fancy to the goat."

"I shore hope he does," grinned Loudon. "It would ease the strain some."

"Make it complete, old beanpole, when you do call the turn. Well, I got to be skippin'. Give my love to old Salt. So long."

"So long."

Johnny Ramsay picked up his reins, wheeled his pony, and fox-trotted away. He felt that further accompanying of Loudon was unnecessary. The danger of an ambush was past. Riding with Loudon had taken Ramsay some fifteen miles out of his way, and twenty-five long miles lay between his pony's nose and the corral bars of the Cross-in-a-box ranch. But Ramsay wasted not a thought on his lengthened journey. He would have ridden cheerfully across the territory and back again in order to benefit a friend.

"Come on, fellah," said Loudon, when Ramsay had gone.

The chestnut moved off at a walk. Loudon did not hurry him. He took out his papers and tobacco and rolled a cigarette with neatness and despatch. Tilting back his head, he blew the first lungful of smoke straight up into the air.

"It wouldn't be right for her to marry him," he observed. "She shore is one pretty girl. I wonder now if I have got any chance. She's rich, an' I ain't, but I shore do love her a lot. Kate Loudon—that's a right nice-soundin' name."

He lowered his head and smoked silently for several minutes. The horse, reins on his neck, swung along steadily.

"Ranger fellah," said Loudon, "she'd ought to be willin' to wait till we make a stake, oughtn't she now? That's right. Wiggle one ear for yes. You know, don't yuh, old tiger-eye?"

When the lights of the ranch sparked across the flat, Ranger pointed his ears, lifted his head, and broke into a foxtrot. Passing the ranch house, on his way to the corral, Loudon heard the merry tinkle of a guitar. Through an open window Loudon saw the squat figure of Mr. Saltoun bent over a desk. On the porch, in the corner where the hammock hung, flickered the glowing tip of a cigarette. With a double thrum of swept strings the guitar-player in the hammock swung from "The Kerry Dance" into "Loch Lomond."

Loudon swore under his breath, and rode on.

Jimmy, the cook, and Chuck Morgan, one of the punchers, were lying in their bunks squabbling over the respective merits of Texas and New Mexico when Loudon entered the bunkhouse. Both men immediately ceased wrangling and demanded letters.

"I ain't read 'em all yet," replied Loudon, dropping his saddle and bridle in a corner. "Wait till to-morrow."

"Jimmy's expectin' one from a red-headed gal," grinned Chuck Morgan. "He's been restless all day. 'Will she write?' says he, 'an' I wonder if she's sick or somethin'.' Don't you worry none, cookie. Them red-headed gals live forever. They're tough, same as a yaller hoss."

"You shut up!" exclaimed Jimmy. "Who'd write to you, you frazzled end of a misspent life? D'jever look at yoreself in the glass? You! Huh! Gimme my letter, Tommy."

"Letter? What letter? I didn't say there was a letter for yuh."

"Well, ain't there?"

"You gimme somethin' to eat, an' then we'll talk about letters."

"You got a nerve!" roared the cook, indignantly. "Comin' rollickin' in 'round midnight an' want yore chuck! Well, there it is"—indicating Chuck Morgan—"go eat it."

"You fry him an' I will. I'll gamble he wouldn't taste any worse than them steaks you've been dishin' out lately."

"You punchers gimme a pain," growled the cook, swinging his legs out of the bunk. "Always eatin,' eatin'. I never seen nothin' like it nohow."

"He's sore 'cause Buff put a li'l dead snake in his bunk," explained Chuck Morgan placidly. "Just a li'l snake—not more'n three foot long at the outside. He shore is the most fault-findin' feller, that Jimmy is."

"There ain't anythin' for yuh, Chuck," said Loudon. "Here's yore letter, Jimmy."

The cook seized the grimy missive and retreated to his kitchen. Twenty minutes later Loudon was eating supper. He ate leisurely. He was in no hurry to go up to the ranch house.

"Got the makin's!" Chuck Morgan's voice was a roar.

"Be careful," said Loudon, turning a slow head. "Yo're liable to strain yore throat, an' for a fellah talkin' as much as you do, that would shore be a calamity."

"It shore would," agreed Morgan. "I only asked yuh for the makin's three times before I hollered."

"Holler first next time," advised Loudon, tossing paper and tobacco across to Morgan. "Have yuh got matches? Perhaps yuh'd like me to roll yuh a pill an' then light it for yuh?"

"Oh, that ain't necessary; none whatever. I got matches. They're all I got left. This aft'noon Jimmy says 'gimme a pipeful,' an' I wants to say right here that any jigger that'll smoke a pipe will herd sheep. 'Gimme a load,' says Jimmy. 'Shore,' says I, an' Jimmy bulges up holdin' the father of all corncobs in his hand. I forks over my bag, an' Jimmy wades in to fill the pipe. But that pipe don't fill up for a plugged nickel.

"He upends my bag, shakes her empty, an' hands her back. 'Thanks,' says Jimmy. 'That's all right,' I says, 'keep the bag, too. It'll fit in right handy to mend yore shirt with, maybe.' Come to find out, that pipe o' Jimmy's hadn't no bottom in her, an' all the tobacco run through an' into a bag Jimmy was holdin' underneath. A reg'lar Injun trick, that is. Yuh can't tell me Jimmy ain't been a squaw-man. Digger Injuns, too, I'll bet."

Jimmy, leaning against the door-jamb, laughed uproariously.

"Yah," he yelped. "I'll teach yuh to steal my socks, I will. I'd just washed a whole pair an' I was a-dryin' 'em behind the house, an' along comes Chuck an' gloms both of 'em, the hawg."

Leaving the two wrangling it out between them, Loudon pushed back his chair and went to the door. For a time he stood looking out into the night. Then he went to his saddle, picked up the bag containing the mail for Mr. Saltoun, and left the bunkhouse.

On the way to the ranch house he took out of his shirt the parcel of ribbon and smoothed it out. Skirting the house on the side farthest from the porch corner where sat Kate and Blakely, Loudon entered the kitchen and walked through the dining room to the open doorway of the office. Mr. Saltoun half turned at Loudon's entrance.

"Hello," said Mr. Saltoun, screwing up his eyes. "I was just wonderin' when you'd pull in."

"'Lo," returned Loudon. "Here's the mail, an' here's a package for Miss Kate."

There was a rush of skirts, and handsome, black-haired Kate Saltoun, her dark eyes dancing, stood in the doorway.

"Did you get my ribbon, Tom?" cried she, and pounced on the flat parcel before Loudon could reply.

She smiled and glowed and held the ribbon under her olive chin, exclaimed over it and thanked Loudon all in a breath. Her father beamed upon her. He loved this handsome girl of his.

"Come out on the porch, Tom," said Kate, "when you're through with father. Mr. Blakely's here. Thank you again for bringing my ribbon."

Kate swished away, and Mr. Saltoun's beaming expression vanished also. Mr. Saltoun was not especially keen. He rarely saw anything save the obvious, but for several weeks he had been under the impression that Kate and this tall, lean puncher with the gray eyes were too friendly.

And here was Kate, while entertaining the 88 manager, inviting Loudon to join her on the porch. Mr. Saltoun was ambitious for his daughter. He had not the remotest intention of receiving into his family a forty-dollar-a-month cowhand. He would have relished firing Loudon. But the latter was a valuable man. He was the best rider and roper in the outfit. Good cowboys do not drift in on the heels of every vagrant breeze.

Mr. Saltoun resolved to keep an eye on Loudon and arrange matters so that Kate and the puncher should meet seldom, if at all. He knew better than to speak to his daughter. That would precipitate matters.

By long experience Mr. Saltoun had learned that opposition always stiffened Kate's determination. From babyhood her father had spoiled her. Consequently the Kate of twenty-three was hopelessly intractable.

Mr. Saltoun drummed on the desk-top with a pencil. Loudon shifted his feet. He had mumbled a non-committal reply to Kate's invitation. Not for a great deal would he have joined the pair on the porch. But Mr. Saltoun did not know that.

"Chuck tells me," said Mr. Saltoun, suddenly, "that he jerked five cows out o' that mud-hole on Pack-saddle Creek near Box Hill. Yeah, that one. To-morrow I want yuh to ride along Pack-saddle an' take a look at them other two holes between Box Hill an' Fishtail Coolee. If yuh see any cows driftin' west, head 'em east. When that —— barb-wire comes—if it ever does, an' I ordered it a month ago—you an' Chuck can fence them three mud-holes. Better get an early start, Tom."

"All right," said Loudon, and made an unhurried withdrawal—by way of the kitchen.

Once in the open air Loudon smiled a slow smile. He had correctly divined the tenor of his employer's thoughts. Before he reached the bunkhouse Loudon had resolved to propose to Kate Saltoun within forty-eight hours.

"I woke up one mornin' on the old Chisolm trail,

Rope in my hand an' a cow by the tail.

Crippled my hoss, I don't know how,

Ropin' at the horns of a 2-U cow."

Thus sang Loudon, carrying saddle and bridle to the corral in the blue light of dawn. Chuck Morgan was before him at the corral, and wrestling with a fractious gray pony.

"Whoa! yuh son of sin!" yelled Morgan, wrenching the pony's ear. "Stand still, or I'll cave in yore slats!"

"Kick him again," advised Loudon, flicking the end of his rope across the back of a yellow beast with a black mane and tail.

The yellow horse stopped trotting instantly. He was rope-broke. It was unnecessary to "fasten," thanks to Loudon's training.

"They say yuh oughtn't to exercise right after eatin'," continued Loudon, genially. "An' yo're mussin' up this nice corral, too, Chuck."

"I'll muss up this nice little gray devil!" gasped Chuck. "When I git on him I'll plow the hide offen him. —— his soul! He's half mule."

"He takes yuh for a relative!" called Jimmy, who had come up unobserved. "Relatives never do git along nohow!"

Jimmy fled, pursued by pebbles. The panting and outraged Chuck returned to his task of passing the rear cinch. Still swearing, he joined Loudon at the gate. The two rode away together.

"That sorrel o' Blakely's," observed Chuck, his fingers busy with paper and tobacco, "is shore as pretty as a little red wagon."

"Yeah," mumbled Loudon.

"I was noticin' him this mornin'," continued Chuck Morgan. "He's got the cleanest set o' legs I ever seen."

"This mornin'," said Loudon, slowly, "Where'd yuh see Blakely's sorrel this mornin'?"

"In the little corral. He's in there with the Old Man's string."

Loudon pulled his hat forward and started methodically to roll a cigarette. So Blakely had spent the night at the ranch. This was the first time he had ever stayed overnight.

What did it mean? Calling on Kate was one thing, but spending the night was quite another.

With the fatuous reasoning of a man deeply in love, Loudon refused to believe that Blakely could be sailing closer to the wind of Kate's affections than he himself. Yet there remained the fact of Blakely's extended visit.

"We've been losin' right smart o' cows lately," remarked Chuck Morgan.

"What's the use o' talkin'?" exclaimed Loudon, bitterly. "The Old Man says we ain't, an' he's the boss."

"He won't say so after the round-up. He'll sweat blood then. If I could only catch one of 'em at it. Just one. But them thievin' 88 boys are plumb wise. An' the Old Man thinks they're little he-angels with four wings apiece."

"Yuh can't tell him nothin'. He knows."

"An' Blakely comes an' sets around, an' the Old Man laps up all he says like a cat, an' Blakely grins behind his teeth. I'd shore like to know his opinion o' the Old Man."

"An' us."

"An' us. Shore. The Old Man can't be expected to know as much as us. You can gamble an' go the limit Blakely has us sized up for sheep-woolly baa-lambs."

Morgan made a gesture of exasperation.

"We will be sheep," exclaimed Loudon, "if we don't pick up somethin' against the 88 before the round-up! We're full-sized, two-legged men, ain't we? Got eyes, ain't we? There ain't nothin' the matter with our hands, is there? Yet them 88 boys put it all over our shirt. Blakely's right. We're related plumb close to sheep, an' blind sheep at that."

"Them 88 boys have all the luck," grunted Chuck Morgan. "But their luck will shore break if I see any of 'em a-foolin' with our cows. So long."

Chuck Morgan rode off eastward. His business was with the cattle near Cow Creek, which stream was one of the two dividing the Bar S range from that of the Cross-in-a-box. Loudon, his eyes continually sliding from side to side, loped onward. An hour later he forded the Lazy River, and rode along the bank to the mouth of Pack-saddle Creek.

The course he was following was not the shortest route to the two mud-holes between Box Hill and Fishtail Coulee. But south of the Lazy the western line of the Bar S was marked by Pack-saddle Creek, and Loudon's intention was to ride along the creek from mouth to source.

There had been no rain for a month. If any cows had been driven across the stream he would know it. Twice before he had ridden the line of the creek, but his labours had not been rewarded. Yet Loudon did not despair. His was a hopeful soul.

Occasionally, as he rode, he saw cows. Here and there on the bank were cloven hoofprints, showing where cattle had come down to drink. But none of them had crossed since the rain. And there were no marks of ponies' feet.

At the mud-hole near Box Hill a lone cow stood belly-deep, stolidly awaiting death.

"Yuh poor idjit," commented Loudon, and loosed his rope from the saddle-horn.

The loop settled around the cow's horns. The yellow pony, cunningly holding his body sidewise that the saddle might not be pulled over his tail, strained with all four legs.

"C'mon, Lemons!" encouraged Loudon. "C'mon, boy! Yuh old yellow lump o' bones! Heave! Head or cow, she's got to come!"

Thus adjured the pony strove mightily. The cow also exerted itself. Slowly the tenacious grip of the mud was broken. With a suck and a plop the cow surged free. It stood, shaking its head.

Swiftly Loudon disengaged his rope, slapped the cow with the end of it, and urged the brute inland.

Having chased the cow a full half-mile he returned to the mud-hole and dismounted. For he had observed that upon a rock ledge above the mud-hole which he wished to inspect more closely. What he had noted was a long scratch across the face of the broad flat ledge of rock. But for his having been drawn in close to the ledge by the presence of the cow in the mud-hole, this single scratch would undoubtedly have escaped his attention.

Loudon leaned over and scrutinized the scratch. It was about a foot long, a quarter of an inch broad at one end, tapering roughly to a point. Ordinarily such a mark would have interested Loudon not at all, but under the circumstances it might mean much. The side-slip of a horse's iron-shod hoof had made it. This was plain enough. It was evident, too, that the horse had been ridden. A riderless horse does not slip on gently sloping rocks.

Other barely visible abrasions showed that the horse had entered the water. Why had someone elected to cross at this point? Pack-saddle Creek was fordable in many places. Below the mud-hole four feet and less was the depth. But opposite the rock ledge was a scour-hole fully ten feet deep shallowing to eight in the middle of the stream. Here was no crossing for an honest man in his senses. But for one of questionable purpose, anxious to conceal his trail as much as possible, no better could be chosen.

"Good thing his hoss slipped," said Loudon, and returned to the waiting Lemons.

Mounting his horse he forded the creek and rode slowly along the bank. Opposite the lower end of the ledge he found that which he sought. In the narrow belt of bare ground between the water's edge and the grass were the tracks of several cows and one pony. Straight up from the water the trail led, and vanished abruptly when it reached the grass.

"Five cows," said Loudon. "Nothin' mean about that jigger."

He bent down to examine the tracks more closely, and as he stooped a rifle cracked faintly, and a bullet whisped over his bowed back.

Loudon jammed home both spurs, and jumped Lemons forward. Plying his quirt, he looked over his shoulder.

A puff of smoke suddenly appeared above a rock a quarter of a mile downstream and on the other side of the creek. The bullet tucked into the ground close beside the pony's drumming hoofs.

Loudon jerked his Winchester from its scabbard under his leg, turned in the saddle, and fired five shots as rapidly as he could work the lever. He did not expect to score a hit, but earnestly hoped to shake the hidden marksman's aim. He succeeded but lamely.

The enemy's third shot cut through his shirt under the left armpit, missing the flesh by a hair's-breadth. Loudon raced over the lip of a swell just as a fourth shot ripped through his hat.

Hot and angry, Loudon jerked Lemons to a halt half-way down the reverse slope. Leaving his horse tied to the ground he ran back and lay down below the crest. He removed his hat and wriggled forward to the top.

Cautiously lifting his head he surveyed the position of his unknown opponent. A half-mile distant, on the Bar S side of the Pack-saddle, was the rock which sheltered the marksman. A small dark dot appeared above it.

Taking a long aim Loudon fired at the dot. As he jerked down the lever to reload, a gray smoke-puff mushroomed out at the lower right-hand corner of the rock, and a violent shock at the elbow numbed his right hand.

Loudon rolled swiftly backward, sat up, and stared wonderingly at his two hands. One held his Winchester, but gripped in the cramped fingers of the right hand was the bent and broken lever of the rifle. The bullet of the sharp-shooting citizen had struck the lever squarely on the upper end, snapped the pin, torn loose the lever, and hopelessly damaged the loading mechanism.

"That jigger can shore handle a gun," remarked Loudon. "If this ain't one lovely fix for a Christian! Winchester no good, only a six-shooter, an' a fully-organized miracle-worker a-layin' for my hide. I'm a-goin' somewhere, an' I'm goin' right now."

He dropped the broken lever and rubbed his numbed fingers till sensation returned. Then he put on his hat and hurried down to his horse.

He jammed the rifle into the scabbard, mounted, and rode swiftly southward, taking great pains to keep to the low ground.

A mile farther on he forded the creek and gained the shelter of an outflung shoulder of Box Hill.

Near the top Loudon tied Lemons to a tree and went forward on foot. Cautiously as an Indian, Loudon traversed the flat top of the hill and squatted down in a bunch of tall grass between two pines. From this vantage-point his field of view was wide. The rock ledge and the mud-hole were in plain sight. So was the rock from which he had been fired upon. It was a long mile distant, and it lay near the crest of a low hog's-back close to the creek.

"He's got his hoss down behind the swell," muttered Loudon. "Wish this hill was higher."

Loudon pondered the advisability of climbing a tree. He wished very much to obtain a view of the depression behind the hog's-back. He finally decided to remain where he was. It was just possible that the hostile stranger might be provided with field glasses. In which case tree-climbing would invite more bullets, and the shooting of the enemy was too nearly accurate for comfort.

Loudon settled himself comfortably in his bunch of grass and watched intently. Fifteen or twenty minutes later what was apparently a part of the rock detached itself and disappeared behind the crest of the hog's-back.

Soon the tiny figure of a mounted man came into view on the flat beyond. Horse and rider moved rapidly across the level ground and vanished behind a knoll. When the rider reappeared he was not more than nine hundred yards distant and galloping hard on a course paralleling the base of the hill.

"Good eye," chuckled Loudon. "Goin' to surround me. I'd admire to hear what he says when he finds out I ain't behind that swell."

The stranger splashed across the creek and raced toward some high ground in the rear of Loudon's old position.

Now that the enemy had headed westward there was nothing to be gained by further delay.

Loudon had plenty of courage, but one requires more than bravery and a six-shooter with which to pursue and successfully combat a gentleman armed with a Winchester.

Hastily retreating to his horse, Loudon scrambled into the saddle, galloped across the hilltop and rode down the eastern slope at a speed exceedingly perilous to his horse's legs. But the yellow horse somehow contrived to keep his footing and reached the bottom with no damage other than skinned hocks.

Once on level ground Loudon headed southward, and Lemons, that yellow bundle of nerves and steel wire, stretched out his neck and galloped with all the heart that was in him.

Loudon's destination was a line-camp twelve miles down the creek. This camp was the temporary abode of two Bar S punchers, who were riding the country south of Fishtail Coulee. Loudon knew that both men had taken their Winchesters with them when they left the ranch, and he hoped to find one of the rifles in the dugout.

With a rifle under his leg Loudon felt that the odds would be even, in spite of the fact that the enemy had an uncanny mastery of the long firearm. Loudon's favourite weapon was the six-shooter, and he was at his best with it. A rifle in his hands was not the arm of precision it became when Johnny Ramsay squinted along the sights. For Johnny was an expert.

"Keep a-travellin', little hoss, keep a-travellin'," encouraged Loudon. "Split the breeze. That's the boy!"

Loudon had more than one reason for being anxious to join issue with the man who had attacked him. At nine hundred yards one cannot recognize faces or figures, but one can distinguish the colour of a horse, and Loudon's antagonist rode a sorrel. Chuck Morgan had said that Blakely's horse was a sorrel.

Loudon sighted the dugout that was Pack-saddle line-camp in a trifle less than an hour. He saw with elation that two hobbled ponies were grazing near by. A fresh mount would quicken the return trip. Loudon's elation collapsed like a pricked bubble when he entered the dugout and found neither of the rifles.

He swore a little, and smoked a sullen cigarette. Then he unsaddled the weary Lemons and saddled the more vicious of the two hobbled ponies. Subjugating this animal, a most excellent pitcher, worked off a deal of Loudon's ill-temper. Even so, it was in no cheerful frame of mind that he rode away to inspect the two mud-holes between Fishtail Coulee and Box Hill.

To be beaten is not a pleasant state of affairs. Not only had he been beaten, but he had been caught by the old Indian fighter's trick of the empty hat. That was what galled Loudon. To be lured into betraying his position by such an ancient snare! And he had prided himself on being an adroit fighting man! The fact that he had come within a finger's breadth of paying with his life for his mistake did not lesson the smart, rather it aggravated it.

Late in the afternoon he returned to the line-camp. Hockling and Red Kane, the two punchers, had not yet ridden in. So Loudon sliced bacon and set the coffee on to boil. Half an hour after sunset Hockling and Kane galloped up and fell upon Loudon with joy. Neither relished the labour, insignificant as it was, of cooking.

"Company," remarked Red Kane, a forkful of bacon poised in the air.

The far-away patter of hoofs swelled to a drumming crescendo. Then inside the circle of firelight a pony slid to a halt, and the voice of cheerful Johnny Ramsay bawled a greeting.

"That's right, Tom!" shouted the irrepressible Johnny. "Always have chuck ready for yore uncle. He likes his meals hot. This is shore real gayful. I wasn't expectin' to find any folks here."

"I s'pose not," said Red Kane. "You was figurin' on romancin' in while we was away an' stockin' up on our grub. I know you. Hock, you better cache the extry bacon an' dobies. Don't let Johnny see 'em."

"Well, o' course," observed Ramsay, superciliously, "I've got the appetite of youth an' a feller with teeth. I don't have to get my nourishment out of soup."

"He must mean you, Hock," said Red Kane, calmly. "You've done lost eight."

"The rest of 'em all hit," asserted Hockling, grinning. "But what Johnny wants with teeth, I dunno. By rights he'd ought to stick to milk. Meat ain't healthy for young ones. Ain't we got a nursin'-bottle kickin' round some'ers, Red?"

"Shore, Red owns one," drawled Loudon. "I seen him buyin' one once over to Farewell at Mike Flynn's."

"O' course," said Johnny, heaping his plate with bacon and beans. "I remember now I seen him, too. Said he was buyin' it for a friend. Why not admit yo're married, Red?"

"Yuh know I bought it for Mis' Shaner o' the Three Bars!" shouted the indignant Kane. "She done asked me to get it for her. It was for her baby to drink out of."

"Yuh don't mean it," said Johnny, seriously. "For a baby, yuh say. Well now, if that ain't surprisin'. I always thought nursin'-bottles was to drive nails with."

In this wise the meal progressed pleasantly enough. After supper, when the four were sprawled comfortably on their saddle-blankets, Loudon launched his bombshell.

"Had a small brush this mornin'," remarked Loudon, "with a gent over by the mud-hole north o' Box Hill."

The three others sat up, gaping expectantly.

"Djuh get him?" demanded Johnny Ramsay, his blue eyes glittering in the firelight.

Loudon shook his head. He raised his left arm, revealing the rent in his shirt. Then he removed his hat and stuck his finger through the hole in the crown.

"Souvenirs," said Loudon. "He busted the lever off my Winchester an' gormed up the action."

"An' he got away?" queried Red Kane.

"The last I seen of him he was workin' in behind where he thought I was."

"Where was you?"

"I was watchin' him from the top o' Box Hill. What did yuh think I'd be doin'? Waitin' for him to surround me an' plug me full o' holes? I come here some hurried after he crossed the creek. I was hopin' you'd have left a rifle behind."

"Wish't we had," lamented Hockling. "Say, you was lucky to pull out of it without reapin' no lead."

"I'll gamble you started the fraycas, Tommy," said Johnny Ramsay.

"Not this trip. I was lookin' at some mighty interestin' cow an' pony tracks opposite the rock ledge when this gent cuts down on me an' misses by two inches."

"Tracks?"

"Yep. Some sport drove five cows on to the ledge an' chased 'em over the creek. That's how they work the trick. They throw the cows across where there's hard ground or rocks on our side. 'Course the rustlers didn't count none on us nosyin' along the opposite bank."

"Ain't they the pups!" ejaculated Hockling.

"They're wise owls," commented Johnny Ramsay. "Say, Tom, did this shootin' party look anyways familiar?"

"The colour of his hoss was—some," replied Loudon. "Blakely was at the ranch last night, an' his hoss was a sorrel."

"What did I tell yuh?" exclaimed Johnny Ramsay. "What did I tell yuh? That Blakely tinhorn is one bad actor."

"I ain't none shore it was him. There's herds o' sorrel cayuses."

"Shore there are, but there's only one Blakely. Oh, it was him all right."

"Whoever it was, I'm goin' to wander over onto the 88 range to-morrow, if Red or Hock'll lend me a Winchester."

"Take mine," said Hockling. "Red's throws off a little."

"She does," admitted Red Kane, "but my cartridges don't. I'll give yuh a hull box."

Followed then much profane comment relative to the 88 ranch and the crass stupidity of Mr. Saltoun.

"I see yo're packin' a Winchester," said Loudon to Johnny Ramsay, when Hockling and Red had turned in.

"Hunter's trip," explained Johnny, his eyes twinkling. "Jack Richie's got his own ideas about this rustlin', so he sent me over to scamper round the 88 range an' see what I could see. I guess I'll travel with you a spell."

"Fine!" said Loudon. "Fine. I was wishin' for company. If we're jumped we'd ought to be able to give 'em a right pleasant little surprise."

Johnny Ramsay rolled a cigarette and gazed in silence at the dying fire for some minutes. Loudon, his hands clasped behind his head, stared upward at the star-dusted heavens. But he saw neither the stars nor the soft blackness. He saw Kate and Blakely, and thick-headed Mr. Saltoun bending over his desk, and he was wondering how it all would end.

"Say," said Johnny Ramsay, suddenly, "this here hold-up cut down on yuh from behind a rock, didn't he?"

"Shore did," replied Loudon.

"Which side did he fire from?"

"Why, the hind side."

"I ain't tryin' to be funny. Was it the left side or the right side?"

"The right side," Loudon replied, after a moment's thought.

"Yore right side?"

"Yep."

"That would make it his left side. Did yuh ever stop to think, Tom, that Blakely shoots a Colt right-handed an' a Winchester left-handed?"

Loudon swore sharply.

"Now, how did I come to forget that!" he exclaimed. "O' course he does."

"Guess Mr. Blakely's elected," said Johnny Ramsay. "Seems likely."

Early next morning Loudon and Ramsay rode northward along the bank of the Pack-saddle. They visited first the boulder a quarter of a mile below the mud-hole. Here they found empty cartridge shells, and the marks of boot-heels.

They forded the creek at the ledge above the mud-hole, where the cows had been driven across, and started westward. They were careful to ride the low ground at first, but early in the afternoon they climbed the rocky slope of Little Bear Mountain. From the top they surveyed the surrounding country. They saw the splendid stretches of the range specked here and there with dots that were cows, but they saw no riders.

They rode down the mountainside and turned into a wide draw, where pines and tamaracks grew slimly. At the head of the draw, where it sloped abruptly upward, was a brushless wood of tall cedars, and here, as they rode in among the trees, a calf bawled suddenly.

They rode toward the sound and came upon a dead cow. At the cow's side stood a lonely calf. At sight of the men the calf fled lumberingly. Ramsay unstrapped his rope and gave his horse the spur. Loudon dismounted and examined the dead cow. When Ramsay returned with the calf, Loudon was squatting on his heels, rolling a cigarette.

"There y'are," observed Loudon, waving his free hand toward the cow. "There's evidence for yuh. Ears slit with the 88 mark, an' the 88 brand over the old Bar S. Leg broke, an' a hole in her head. She ain't been dead more'n a day. What do you reckon?"

"That the 88 are damn fools. Why didn't they skin her?"

"Too lazy, I guess. That calf's branded an' earmarked all complete. Never was branded before, neither."

"Shore. An' the brand's about two days old. Just look at it. Raw yet."

"Same date as its ma's. They done some slick work with a wet blanket on that cow, but the Bar S is plain underneath. Give the cow a month, if she'd lived, an' yuh'd never know but what she was born 88."

"Oh, they're slick, the pups!" exclaimed Johnny Ramsay.

"The Old Man ought to see this. When Old Salt throws his eyes on that brandin' I'll gamble he'll change his views some."

"You bet he will. Better start now."

"All right. Let's get a-goin'."

"One's enough. You go, Tommy. I'll stay an' caper around. I might run onto somethin'. Yuh can't tell."

"I'd kind o' like to have yuh here when I get back."

"Don't worry none. From what I know o' Old Salt you an' him won't be here before to-morrow mornin'! I'll be here then."

"All right. I'll slide instanter. So long, Johnny."

"This is a devil of a time to haul a man out o' bed," complained Mr. Saltoun, stuffing the tail of his nightshirt into his trousers. "C'mon in the office," he added, grumpily.

Mr. Saltoun, while Loudon talked, never took his eyes from the puncher's face. Incredulity and anger warred in his expression.

"What do you reckon?" the owner inquired in a low tone, when Loudon fell silent.

"Why, it's plain enough," said Loudon, impatiently. "The rustlers were night-drivin' them cows when one of 'em busted her leg. So they shot her, an' the calf got away an' come back after the rustlers had gone on. They must 'a' been night-drivin', 'cause if it had been daytime they'd 'a' rounded up the calf. Night-drivin' shows they were in a hurry to put a heap o' range between themselves an' the Bar S. They were headin' straight for the Fallin' Horse an' the Three Sisters."

"I see all that. I'm still askin' what do you reckon?"

"Meanin'?"

"Who-all's doin' it?"

"I ain't changed my opinion any. If the rustlers don't ride for the 88, then they're related mighty close."

"You can't prove it," denied Mr. Saltoun.

"I know I can't. But it stands to reason that two or three rustlers workin' for themselves wouldn't drift cows west—right across the 88 range. They'd drift 'em north toward Farewell, or south toward the Fryin' Pans. Findin' that cow an' calf on the 88 range is pretty near as strong as findin' a man ridin' off on yore hoss."

"Pretty near ain't quite."

"I ain't sayin' anythin' more."

"You've got a grudge against the 88, Tom. Just because a left-handed sport on a sorrel cuts down on yuh it don't follow that Blakely is the sport. Yuh hadn't ought to think so, Tom. Why, Blakely stayed here the night before yuh started for Pack-saddle. He didn't leave till eight o'clock in the mornin', an' then he headed for the 88. It ain't likely he'd slope over to the creek an' shoot you up. Why, that's plumb foolish, Tom. Blakely's white, an' he's a friend o' mine."

Mr. Saltoun gazed distressedly at Loudon. The puncher stared straight before him, his expression wooden. He had said all that he intended to say.

"Well, Tom," continued the owner, "I don't enjoy losin' cows any more than the next feller. We've got to stop this rustlin' somehow. In the mornin' I'll ride over with yuh an' have a look at that cow. Tell Chuck Morgan I want him to come along. Now you get some sleep, an' forget about the 88. They ain't in on this deal, take my word for it."

It was a silent trio that departed in the pale light of the new day. Chuck Morgan endeavoured to draw Loudon into conversation but gave it up after the first attempt. The heavy silence remained unbroken till they reached the mouth of the wide draw beyond Little Bear Mountain.

"There's a hoss," said Loudon, suddenly.

A quarter of a mile away grazed a saddled pony. Loudon galloped forward.

The animal made no attempt to escape. It stood quietly while Loudon rode up and gathered in the reins dragging between its feet. The full cantenas were in place. The quirt hung on the horn. The rope had not been unstrapped. The slicker was tied behind the cantle. Under the left fender the Winchester was in its scabbard. All on the saddle was as it should be.

"Whose hoss?" inquired Mr. Saltoun, who had followed more slowly.

"Ramsay's," replied the laconic Loudon, and started up the draw at a lope, leading the riderless pony.

Loudon's eyes searched the ground ahead and on both sides. He instinctively felt that some ill had befallen Johnny Ramsay. His intuition was not at fault.

When the three had ridden nearly to the head of the draw, where the trees grew thickly, Loudon saw, at the base of a leaning pine, the crumpled body of Johnny Ramsay.

Loudon dropped from the saddle and ran to his friend. Ramsay lay on his back, his left arm across his chest, his right arm extended, fingers gripping the butt of his six-shooter. His face and neck and left arm were red with blood. His appearance was sufficiently ghastly and death-like, but his flesh was warm.

Respiration was imperceptible, however, and Loudon tore open Ramsay's shirt and pressed his ear above the heart. It was beating, but the beat was pitifully slow and faint.

Loudon set to work. Chuck Morgan was despatched to find water, and Mr. Saltoun found himself taking and obeying orders from one of his own cowpunchers.

An hour later Ramsay, his wounds washed and bandaged, began to mutter, but his words were unintelligible. Within, half an hour he was raving in delirium. Chuck Morgan had departed, bound for the Bar S, and Loudon and Mr. Saltoun sat back on their heels and watched their moaning patient.

"It's a whipsaw whether he'll pull through or not," remarked the bromidic Mr. Saltoun.

"He's got to pull through," declared Loudon, grimly. "He ain't goin' to die. Don't think it for a minute."

"I dunno. He's got three holes in him."

"Two. Neck an' arm, an' the bone ain't touched. That graze on the head ain't nothin'. It looks bad, but it only scraped the skin. His neck's the worst. A half inch over an' he'd 'a' bled to death. Yuh can't rub out Johnny so easy. There's a heap o' life in him."

"His heart's goin' better now," said Mr. Saltoun.

Loudon nodded, his gray eyes fixed on the bandaged head of his friend. Conversation languished, and Mr. Saltoun began to roll and smoke cigarettes. After a time Loudon rose.

"He'll do till the wagon comes," he said. "Let's go over an' take a squint at that cow."

Loudon led Mr. Saltoun to the spot where lay the dead cow. When the puncher came in sight of the dead animal he halted abruptly and observed that he would be damned.

Mr. Saltoun whistled. The cow had been thoroughly skinned. Beside the cow lay the calf, shot through the head. And from the little body every vestige of hide had been stripped.

"I guess that settles the cat-hop," said Mr. Saltoun, and began comprehensively to curse all rustlers and their works.

It was not the skinning that disturbed Mr. Saltoun. It was the sight of his defunct property. The fact that he was losing cows had struck home at last. Inform a man that he is losing property, and he may or may not become concerned, but show him that same property rendered valueless, and he will become very much concerned. Ocular proof is a wonderful galvanizer. Yet, in the case of Mr. Saltoun, it was not quite wonderful enough.

"Oh, they're slick!" exclaimed Loudon, bitterly. "They don't forget nothin'! No wonder Blakely's a manager!"

Mr. Saltoun ceased swearing abruptly.

"Yo're wrong, Tom," he reproved. "The 88's got nothin' to do with it. I know they ain't, an' that's enough. I'm the loser, not you, an' I'm the one to do the howlin'. An' I don't want to hear any more about the 88 or Blakely."

Loudon turned his back on Mr. Saltoun and returned to the wounded man. The cowboy yearned to take his employer by the collar and kick him into a reasonable frame of mind. Such blindness was maddening.

Mr. Saltoun heaped fuel on the fire of Loudon's anger by remarking that the rustlers undoubtedly hailed from the Frying-Pan Mountains. Loudon, writhing internally, was on the point of relieving his pent-up feelings when his eye glimpsed a horseman on the high ground above the draw. The puncher reached for his Winchester, but he laid the rifle down when the rider changed direction and came toward them.

"Block, ain't it?" inquired Mr. Saltoun.

Loudon nodded. His eyes narrowed to slits, his lips set in a straight line. The sheriff rode up and halted, his little eyes shifting from side to side. He spoke to Mr. Saltoun, nodded to Loudon, and then stared at the wounded man.

"Got a rustler, I see," he observed dryly, his lips crinkled in a sneering smile.

"Yuh see wrong—as usual," said Loudon. "Some friend o' yores shot Johnny."

"Friend o' mine? Who?" queried the sheriff, his manner one of mild interest.

"Wish I knew. Thought yuh might be able to tell me. Ain't that what yuh come here for?"

"Ramsay's shot—that's all we know," interposed Mr. Saltoun, hastily. "An' there's a cow an' calf o' mine over yonder. Skinned, both of 'em."

"An' the cow had been branded through a wet blanket," said Loudon, not to be fobbed off. "The Bar S was underneath an' the 88 was on top. Johnny an' me found the dead cow an' the live calf yesterday. I left Johnny here an' rode in to the Bar S. When we got here we found Johnny shot an' the cow an' calf skinned. What do you guess?"

"I don't guess nothin'," replied the sheriff. "But it shore looks as if rustlers had been mighty busy."

"Don't it?" said Loudon with huge sarcasm. "I guess, now——"

"Say, look here, Sheriff," interrupted Mr. Saltoun, anxious to preserve peace, "I ain't makin' no charges against anybody. But this rustlin' has got to stop. I can't afford to lose any more cows. Do somethin'. Yo're sheriff."

"Do somethin'!" exclaimed the Sheriff. "Well, I like that! What can I do? I can't be in forty places at once. Yuh talk like I knowed just where the rustlers hang out."

"Yuh probably do," said Loudon, eyes watchful, his right hand ready.

"Keep out of this, Tom," ordered Mr. Saltoun, turning on Loudon with sharp authority. "I'll say what's to be said."

"Show me the rustlers," said the sheriff, electing to disregard Loudon's outburst. "Show me the rustlers, an' I'll do the rest."

At which remark the seething Loudon could control himself no longer.

"You'll do the rest!" he rapped out in a harsh and grating voice. "I guess yuh will! If yuh was worth a —— yuh'd get 'em without bein' shown! How much do they pay yuh for leavin' 'em alone?"

The sheriff did not remove his hands from the saddle-horn. For Loudon had jerked out his six-shooter, and the long barrel was in line with the third button of the officer's shirt.

"Yuh got the drop," grunted the sheriff, his little eyes venomous, "an' I ain't goin' up agin a sure thing."

"You can gamble yuh ain't. I'd shore admire to blow yuh apart. You git, an' git now."

The sheriff hesitated. Loudon's finger dragged on the trigger. Slowly the sheriff picked up his reins, wheeled his horse, and loped away.

"What did yuh do that for?" demanded Mr. Saltoun, disturbed and angry.

Loudon, his eye-corners puckered, stared at the owner of the Bar S. The cowboy's gaze was curious, speculative, and it greatly lacked respect. Instead of replying to Mr. Saltoun's question, Loudon sheathed his six-shooter, squatted down on his heels and began to roll a cigarette.

"I asked yuh what yuh did that for?" reiterated blundering Mr. Saltoun.

Again Loudon favoured his employer with that curious and speculative stare.

"I'll tell yuh," Loudon said, gently. "I talked to Block because it's about time someone did. He's in with the rustlers—Blakely an' that bunch. If you wasn't blinder'n a flock of bats you'd see it, too."

"You can't talk to me this way!" cried the furious Mr. Saltoun.

"I'm doin' it," observed Loudon, placidly.

"Yo're fired!"

"Not by a jugful I ain't. I quit ten minutes ago."

"You——" began Mr. Saltoun.

"Don't," advised Loudon, his lips parting in a mirthless smile.

Mr. Saltoun didn't. He withdrew to a little distance and sat down. After a time he took out his pocket-knife and began to play mumblety-peg. Mr. Saltoun's emotions had been violently churned. He required time to readjust himself. But with his customary stubbornness he held to the belief that Blakely and the 88 were innocent of evil-doing.

Until Chuck Morgan and the wagon arrived early in the morning, Loudon and his former employer did not exchange a word.

Johnny Ramsay was put to bed in the Bar S ranch house. Kate Saltoun promptly installed herself as nurse. Loudon, paid off by the now regretful Mr. Saltoun, took six hours' sleep and then rode away on Ranger to notify the Cross-in-a-box of Ramsay's wounding.

An angry man was Richie, manager of the Cross-in-a-box, when he heard what Loudon had to say.

The following day Loudon and Richie rode to the Bar S. On Loudon's mentioning that he was riding no longer for the Bar S, Richie immediately hired him. He knew a good man, did Jack Richie of the Cross-in-a-box.

When they arrived at the Bar S they found Johnny Ramsay conscious, but very weak. His weakness was not surprising. He had lost a great deal of blood. He grinned wanly at Loudon and Richie.

"You mustn't stay long," announced Miss Saltoun, firmly, smoothing the bed-covering.

"We won't, ma'am," said Richie. "Who shot yuh, Johnny?"

"I dunno," replied the patient. "I was just a-climbin' aboard my hoss when I heard a shot behind me an' I felt a pain in my neck. I pulled my six-shooter an' whirled, an' I got in one shot at a gent on a hoss. He fired before I did, an' it seems to me there was another shot off to the left. Anyway, the lead got me on the side of the head an' that's all I know."

"Who was the gent on the hoss?" Loudon asked.

"I dunno, Tom. I hadn't more'n whirled when he fired, an' the smoke hid his face. It all come so quick. I fired blind. Yuh see the chunk in my neck kind o' dizzied me, an' that rap on the head comin' on top of it, why, I wouldn't 'a' knowed my own brother ten feet away. I'm all right now. In a couple o' weeks I'll be ridin' the range again."

"Shore yuh will," said Loudon. "An' the sooner the quicker. You've got a good nurse."

"I shore have," smiled Johnny, gazing with adoring eyes at Kate Saltoun.

"That will be about all," remarked Miss Saltoun. "He's talked enough for one day. Get out now, the both of you, and don't fall over anything and make a noise. I'm not going to have my patient disturbed."

Loudon went down to the bunkhouse for his dinner. After the meal, while waiting for Richie, who was lingering with Mr. Saltoun, he strove to obtain a word with Kate. But she informed him that she could not leave her patient.

"See you later," said Miss Saltoun. "You mustn't bother me now."

And she shooed him out and closed the door. Loudon returned to the bunkhouse and sat down on the bench near the kitchen. Soon Jimmy appeared with a pan of potatoes and waxed loquacious as was his habit.

"Who plugged Johnny? That's what I'd like to know," wondered Jimmy. "Here! leave them Hogans be! They're to eat, not to jerk at the windmill. I never seen such a kid as you. Yo're worse than Chuck Morgan, an' he's just a natural-born fool. Oh, all right. I ain't a-goin' to talk to yuh if yuh can't act decent."

Jimmy picked up his pan of potatoes and withdrew with dignity. The grin faded from Loudon's mouth, and he gazed worriedly at the ground between his feet.

What would Kate say to him? Would she be willing to wait? She had certainly encouraged him, but—— Premonitory and unpleasant shivers crawled up and down Loudon's spinal column. Proposing was a strange and novel business with him. He had never done such a thing before. He felt as one feels who is about to step forth into the unknown. For he was earnestly and honestly very much in love. It is only your philanderer who enters upon a proposal with cold judgment and a calm heart.

Half an hour later Loudon saw Kate at the kitchen window. He was up in an instant and hurrying toward the kitchen door. Kate was busy at the stove when he entered. Over her shoulder she flung him a charming smile, stirred the contents of a saucepan a moment longer, then clicked on the cover and faced him.

"Kate," said Loudon, "I'm quittin' the Bar S."

"Quitting? Oh, why?" Miss Saltoun's tone was sweetly regretful.

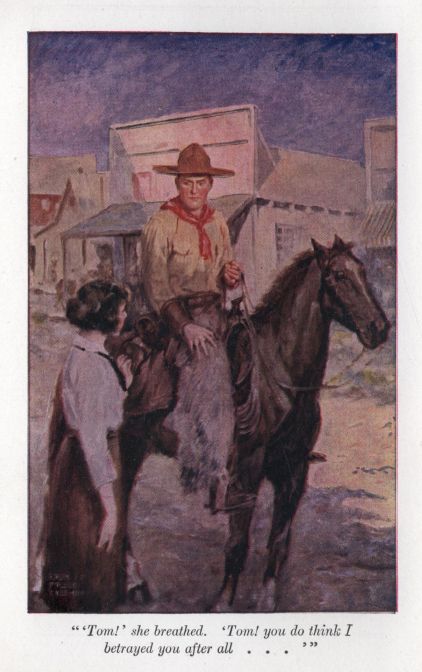

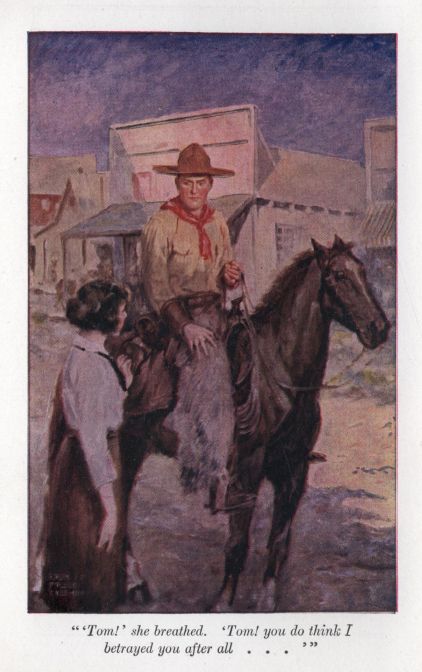

"Lot o' reasons. I'm ridin' for the Cross-in-a-box now."