The Project Gutenberg EBook of Through Shot and Flame, by J. D. Kestell

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Through Shot and Flame

The Adventures and Experiences of J. D. Kestell Chaplain

to President Steyn and General Christian De Wet

Author: J. D. Kestell

Release Date: August 14, 2011 [EBook #37083]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THROUGH SHOT AND FLAME ***

Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THROUGH SHOT

AND FLAME

THE ADVENTURES AND EXPERIENCES OF

J. D. KESTELL

CHAPLAIN TO PRESIDENT STEYN

AND

GENERAL CHRISTIAN DE WET

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

1903

Colonial Library

TO

MY WIFE

WHO WAS ONE OF THE THOUSANDS

WHO ENDURED IN THE GREAT STRUGGLE

FOR FREEDOM, I DEDICATE THIS BOOK

AND

WITH HER I COMMEMORATE HERE THE

FIDELITY AND PATRIOTISM OF HIM WHO

WAS MY COMRADE IN THE FIELD, AND

WHO DIED IN THE SPRINGTIDE OF HIS

LIFE, A PRISONER OF WAR, AT LADYSMITH,

NATAL

Our Son, CHARLES KESTELL

(p. 3) THROUGH SHOT AND FLAME

PART I

HOPE

CHAPTER I

I JOIN THE HARRISMITH COMMANDO

I purpose to chronicle in the following pages my experiences of the war

between the Boers and the English. It is my object to record what I went

through on commando, and to give the reader an idea, according to my own

observation, of the struggles and sufferings of a small nation against

the overwhelming odds of an Empire—nay, against the world itself.

For was it not against the world that the little nation fought?

Think of it. Not only did England have 240,000 men in the field against

45,000 of the two South African Republics; not only did she have more

guns than the two little States, much more ammunition, a much greater

amount of supplies, a great many more horses, much more money—but she

had the world also on her side. The world looked on the strife without

putting forth a hand to help the weak against the strong: nay, it helped

the strong. The United States of North America sold horses and wheat

(p. 4) and meat to the mighty Empire, that was carrying on a war of

extermination against the two small States in South Africa; the

Republics of South America gave mules; Austria and Russia supplied

horses. I do not forget, when I say this, the large sympathy which the

world showed us. I should be guilty of the most heinous ingratitude if I

did not acknowledge that the world, and especially Holland, went out of

its way in liberally supplying clothing and large sums of money to our

women and children in the concentration camps, and to the prisoners of

war on the islands. But England had the advantage of a market almost

wherever she wished to buy; and she closed up every avenue through which

we might have been aided. And so the little nation stood alone, while

its great adversary was assisted from the four corners of the earth.

Now I purpose to put on record my experiences in this strife. I will do

so as well as I can. What I have to relate, however, will by no means be

a history of the war.—We shall not have a history of the war until our

children write it.—No, I am not going to write a history: I am going to

record my limited experiences. You will not find here, for instance,

anything about the events which happened at Stormberg or Magersfontein,

or about the taking of Bloemfontein or Pretoria. I was not present at

those events. Only on that of which I was an eye-witness, or on what

took place in the commando to which I belonged at the time, or what came

to my notice shortly after its occurrence—only on that will I report in

these pages.

But let me tell you before I proceed, that I accompanied the burghers

only as a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church. I was never armed. I

never took part in a fight as a soldier. I never meddled with military

matters. All that, I felt, lay outside of my province. And yet, as will

appear in (p. 5) what follows, I fought in the great fight. I was often

in action, and if I carried no arms, I carried a pouch of bandages. My

presence in a fight gave heart to some and eased the pain of others. I

fought, too, in another way: I encouraged the burghers in every service

I held, just as every chaplain ought to do, and admonished them to

persevere in the great fight. But I never forgot that I was a minister

of religion. Every Sunday, and whenever I had an opportunity in the

week, I conducted divine service, taking, as a rule, my text from the

Old Testament. Besides this I devoted myself to ambulance work, without,

however, ever wearing a Red Cross on my sleeve.

I need not say that I was heart and soul one with the great cause of the

Republics. Nothing lay nearer to my heart than their welfare; and when

it appeared that war was imminent, and that it would be disastrous to my

people, it weighed upon my mind like lead.

War?—Ay, war! I feared a collision with England from the moment that

Sir Alfred Milner proved at the Bloemfontein Conference that nothing

could satisfy him. I became convinced then of what I had all along

suspected, but would not believe, that the object of England was not to

see that the Uitlander should obtain his rights, but that the two

Republics should be annihilated, and that the map of South Africa

should, as Rhodes had put it, be painted red.

These suspicions of mine soon proved not to have been unfounded.

President Kruger had consented, at last, to grant the franchise to

Uitlanders, after a residence of five years in the country; and

everybody thought now that war was averted, and that there would be a

peaceful adjustment of the differences between England and the South

African Republic. But England did not want that. England wanted the

Transvaal. Contrary to the expectations of everyone, (p. 6) the British

Government did not accept the proposal of President Kruger, and said

that it would dictate its own terms. It was speedily seen that England

intended to do this by force of arms, for numbers of British troops had

begun to mass on the boundaries of the two Republics.

At last England got what it had been seeking—a palpable causa belli,

in the Ultimatum which the Transvaal Government, wearied to death, at

last issued.

Both Boers and Britishers have declared that it was a fatal mistake on

the part of the Transvaal to issue the Ultimatum. The Boers said that

President Kruger should have waited until England had begun hostilities;

and the English protested that there would have been no war, if there

had been no Ultimatum. Lord Salisbury, especially, has never wearied in

his attempt to make the world believe that England went to war with the

Republics solely because of the insult offered by the Ultimatum; and

that the two States themselves had by that act made it impossible for

the British Government to permit them to retain their independence.

But the world knows better.

The world knows that it was England, not the Republics, that began the

quarrel, when, contrary to the terms of the Convention of 1884, she

interfered with the internal affairs of the South African Republic; when

later on she would listen to no proposal of the Transvaal Government,

and when she began sending troops to the boundaries of the two States.

The world can comprehend also that the Republics could not wait until

England had completed the massing of her troops on the borders, to wake

up one morning and find themselves invaded from every side. The world,

too, knows what must be said of the blow which falls in a manner

mechanically, after unendurable provocation. And posterity, sitting in

(p. 7) judgment, will pass its verdict on the Ultimatum. It will say

that it was a protest against wrong and oppression. It will hear a

little people speaking through that Ultimatum to a great nation: "Thou

art great and mighty, and thou wouldst set thy foot upon my neck; but I

declare here before the whole world that Might is not Right; and I defy

thee!"

I cannot enter into a discussion here of the question whether the South

African Republic wronged the Uitlanders. But if this had been the case,

was England then the knight-errant among the nations of the earth, to

rush to the succour of such as might be oppressed by the one or the

other Power?—And if she considered that this was her mission, why did

she never attempt to teach Turkey, Russia, even the United States of

America, what their duty was?

Nothing was further removed from the thoughts of England than such

disinterestedness. But she imagined that she had a chance with this

little people; and when she wished to beat the dog, she found a stick in

the grievances of the Uitlanders.

Poor Transvaal, thou wert not perfect—far from that! But thou hadst had

no time to become so. Thou hadst had no time to develop into what thou

wouldst have become in the course of years. Thy great neighbour, arrived

at maturity through centuries of imperfections, found thee a child, and,

counting it a crime in thee to be a child, made a murderous assault on

thee!

The negotiations between England and the South African Republic were

still progressing when England sent troops, not only to the Transvaal,

but also the Free State borders. What else but undisguised hostility

could the Governments of the two Republics see in this action of

England? They were compelled by it to prepare themselves for any

emergency; and enjoined, in consequence, the landdrosts to instruct

(p. 8) the commandants of all the districts of the two States to

commandeer the burghers. This commandeering took place on 2nd of October

1899. It was on Sunday, and many a Boer had gathered his household

around him, and was sitting with his Bible open before him, while he was

conducting his Sunday family worship, when the field-cornet, or other

person sent in his stead, came and told him that he had to appear at a

certain place, with his horse, saddle and bridle, rifle and thirty

rounds of ammunition, and rations for eight days.

The Harrismith Commando was ordered to muster on the farm—The Oaks;

and most of the burghers composing it arrived there next day. We

proceeded thence to Tantjesberg, and approached in the course of a few

days the boundary between the Orange Free State and Natal, on the grand

range of the Drakensberg. To this border other Free State commandos

numbering in all about 8000 men came, while a like number were sent to

the western boundary, and a small force to the Basutoland line.

The southern border of the district of Harrismith was the line which had

to be guarded, between the Orange Free State and Natal. The commandos,

therefore, which had come from other places to this boundary, had to

pass somewhere through the district of Harrismith. This happened in due

course. During the week all the commandos passed east or west of, or

through the town. The Bethlehem burghers pitched their laager on the

south-west near Binghamsberg, a precipitous mountain which Erasmus Smit,

the missionary who accompanied the Voortrekkers, called Kerkenberg

(Church Hill) in his Journal. This he did because a great cleft of a

tremendous rock at the foot of the mountain, in which the name of Piet

Retief is written in green paint, afforded ample space for conducting

divine worship. The Heilbron Commando went to Bezuidenhout's Pass, and

the (p. 9) Kroonstad to Tintwa. The burghers of Winburg marched past on

the east of Platberg, and pitched their camp at Van Reenen, near the

line of railway; while the men of the Harrismith and Vrede Commandos

went farther east to Botha's Pass, and formed the connection with the

line of the Transvaal forces on the west of Majuba.

It rained a great deal when these Boer forces hastened to the

Drakensberg. I remember very well how the Heilbron and Kroonstad

burghers rode through the town of Harrismith in the rain.

Notwithstanding the depressing nature of the weather, everybody was

cheerful, and all looked with boundless trust in God into the future.

The Heilbron burghers did not remain in the town, but the men of

Kroonstad waited at the church until their greatcoats and blankets,

which they hung on the railings, were dry. Meanwhile our women poured

out warm coffee for the men, and began thus to take their share in the

great strife, which had begun.

I must here make mention of the manner in which the Government took the

interests to heart of such as had been deprived of their employment

through the new state of things. It appointed a commission in every

town, whose duty it was to inquire into the condition of the needy and

to distribute flour and mealie meal, wherever they found that there was

great want. The Government also afforded facilities to the poor of

earning money. It supplied the material for shirts and trousers, to be

made for such burghers on commando as were in need, and paid a small sum

for every garment that was made. The wives of the landdrosts and

ministers were intrusted with this department. Besides this, the women

of the towns were asked to bake biscuits—the Government supplying the

flour for the commandos. It was beautiful to see how willingly the women

undertook this hard labour. Some of them baked (p. 10) as much as a bag

of flour in a day; and I have seen at the Harrismith Station truck loads

of biscuits ready to be carried to the forces in Natal.

This baking of biscuits was one of the first proofs of the devotion and

self-sacrifice of our women.

But I have anticipated a little.

At five o'clock on the 11th October 1899 the forty-eight hours, which

were given by the Transvaal to England to decide whether she would

withdraw her troops from the borders of the Republics, had elapsed.

England had not withdrawn her troops, and it was now clear to everyone

that she desired war. Everyone knew also now that from that hour we were

in a state of war.

It was now the interest of every chief-commandant (Hoofd-commandant) to

occupy the best positions, if possible before the English could do so.

With this in view, orders were given that all commandos should be sent

forward with the utmost speed, and take positions on the Drakensberg.

This was done, and by the 13th of October all the passes on the great

mountain range were guarded by our forces.

On the same day a meeting of Free State officers was held in the tent of

General Marthinus Prinsloo, and the question was there discussed whether

a flying column should not, without delay, proceed west of Ladysmith and

blow up the railway bridge over the Tugela at Colenso. Most of the

officers were opposed to this idea, but it was resolved instead that

portions of the commandos of Heilbron, Winburg, Kroonstad, and

Harrismith should descend into Natal that very night, under the command

of Commandant C. J. de Villiers, who was temporarily appointed General

in the place of General A. P. Cronje. This force would have to

co-operate with the Transvaal commandos and endeavour to cut off the

retreat of the English at Dundee.

I was present when the Harrismith men were (p. 11) ready to go. How

well I remember the command given by the brave and never-to-be-forgotten

Field-Cornet Jan Lyon—

"Four deep!"

I see him in my mind's eye now, while I write, placing himself, every

inch a soldier, at the head of his men and riding away.

After him came Field-Cornet Z. J. de Beer with the Harrismith town

burghers. They rode past in splendid form, with the Free State flag

bravely fluttering in the breeze. Something thrilled through my being

when I saw these men, all of whom I knew, ride away into the great

unknown. I knew that some of them would never tread Free State soil

again.

And it happened sooner than I thought.

Next day Field-Cornet de Beer collided with the Carbineers not far from

Bester's Station, and the first burgher of the Harrismith Commando was

killed. To the best of my knowledge he was the first victim of the war:

his name was Jonson.

The Carbineers had attacked the men of Field-Cornet de Beer on a ridge,

and bombarded them with a Maxim. Our burghers held their ground until

Field-Cornet Lyon arrived with a reinforcement and charged the

Carbineers on their right wing. The English could not resist this

onslaught and betook themselves to flight, never resting until they

arrived out of breath at Ladysmith. One of their officers, Lieutenant

Galway, was taken prisoner, and sent to Harrismith. The camp of the

Carbineers also fell into our hands, and the burghers were immensely

pleased with the little light green tents they found. These were very

portable, and went far and wide with the burghers in later stages of the

war.

After addressing the Winburg men, I had returned to Harrismith on the

morning of the 18th, and was an eye-witness of the intense excitement

of the town (p. 12) during the next few days, when news of battles

fought in the north of Natal arrived. We heard of the fight at Glencoe

on the 20th October, at Elandslaagte on the 21st, and at Rietfontein

(Modderspruit) on the 24th. In the first two the Transvaalers had been

engaged, in the last the Free Staters.

I was very strongly affected, and felt after the news of Rietfontein

came that I could not remain at Harrismith. I therefore decided to go to

Natal without delay and join the Harrismith Commando. On Friday the 27th

October I took leave of my wife and children, and arrived in the

afternoon at the headquarters of General Marthinus Prinsloo. He was very

kind, and provided a cart for my journey and that of Dr. Cilliers who

also wished to go into Natal. Next day I arrived at Bester's Station,

and had the opportunity of visiting the burghers who had been wounded in

the fight at Rietfontein. I was especially glad to see Mr. Jacobus de

Jager of Loskop. As he was temporarily hors de combat, he offered me a

horse and his own saddle for a time. I was of course very grateful and

accepted his offer with alacrity.

After breakfast, next morning, I set out with the object of finding the

Harrismith Commando, and soon came to Smith's Crossing. There I saw what

a farm looked like where looting had taken place. Some of our burghers

had destroyed everything there that was not firmly built on, or planted

in the ground. The windows were smashed, the doors torn off, and

everything that was of value or use was carried away. Presses and chests

of drawers had been broken open, furniture dashed to pieces, pillows and

mattresses cut open, and everywhere about there were lying scattered in

dreadful confusion, feathers of pillows and beds, pieces of furniture,

torn books, photographs, plates, pots, pans, even articles of female

attire.

The sight of this affected me very unfavourably, as I found it did many

others too. Several (p. 13) remarked that we were not fighting for

booty, but for the sacred cause of our independence. But the foreigners

fighting among us against England laughed at our scruples. Destruction

of property, they said, was a part of the war, and England would destroy

our farms worse when once she began.

None of us would believe this assertion of the foreigners then. We know

now how true it was. It is nearly three years now since I looked at the

destruction at Smith's Crossing, and what have I not seen since of the

destruction carried out by England? Everything done by the Boers is as

dust in the balance, when compared with the devastation carried out by

the British soldiers.

Now English officers, when taxed with the barbarity with which they

devastated the farms in the two Republics, have been accustomed to

retort that it was we who began the game. To this it can be replied that

the Boers destroyed the houses of those only who had fled from their

farms, and had thus shown that they were hostile to us; that even this

was not done by order of the Boer Generals, nay, was done contrary to

the express orders forbidding the destruction of farms, and that it was

never carried out so ruthlessly as it was later by the English troops.

The houses were never committed to the flames by the Boers, nor did they

blow up any farmstead with dynamite. But the steadings in the Free State

and Transvaal were destroyed by fire or dynamite by order of a British

Field-Marshal, and later of a British Commander-in-Chief. And there were

hundreds of cases where this took place over the heads of women and

children, who were immediately after the destruction exposed to the wet

weather in summer and the cold of winter. Nothing approaching such

barbarity was ever done by the Boers. If, therefore, the English were

making reprisals in burning the farms, they avenged themselves not as

(p. 14) Cain seven times, but as Lamech seventy times seven.

I did not have to go far from Smith's Crossing. I found the Harrismith

burghers three miles to the west of Ladysmith, near the homestead of Mr.

Gert Potgieter. They consisted of what was called a horse-commando, they

were encumbered with no convoy, and only two or three waggons (one of

them carrying ammunition) stood about. The difference between the camp

here and the great laagers on the Drakensberg, with their walls of

encircling waggons, struck me. Here there was nothing besides the little

brown canvas Free State tents, and the beautiful little green tents

taken from the Carbineers on the 18th. One would be much in want of many

things, I thought, in a horse-commando, and life in it would be in the

utmost degree repulsive, to a person especially with studious

predilections, to whom the four walls of a study were more attractive

than the wide, wide plains under the great blue vault above. I thought

so then, but the time was coming when we should not have even little

Carbineer tents.

However inhospitable a "horse-commando" appeared, the burghers were not

so. They were mostly members of my congregation, and received me with

the utmost cordiality. They gave me something to eat—just what they had

ready—Kaboemielies, (boiled maize). What better—what more nutritious

food could they have given me than mealies? Many a Boer poet has sung

the praises of the mealies, but the inspiration of each has failed.

The day after I arrived in the laager, the 30th October, the battle of

Nicholson's Nek was fought. It was in this fight that Christian de Wet

made his first appearance. He was then an acting Commandant, and led

about 200 men up the hill, where he captured 800 British troops. The

Transvaal burghers were also engaged that day and took 400 soldiers

(p. 15) prisoners, so that we captured 1200 in all. I was not present. I

only saw from a great distance our shells exploding on the battlefield,

and I can therefore give no description of what took place.

I met the Rev. P. Roux, who was subsequently appointed General, next

day. He told me that he came on the scene just when the fight was over.

He had been struck, he said, by the distress of the wounded. It was

terrible to see what they were suffering in the broiling sun. He had

also spoken to several English officers. One had said in a surly tone of

voice: "This is only a beginning." Mr. Roux had replied: "Yes, and we

are quite satisfied with it."

(p. 16) CHAPTER II

A NIGHT MARCH

It was decided to invest Ladysmith, and the Free State burghers were

ordered to occupy positions towards the north-west, west, and south of

the town. The Transvaalers took the opposite ridges and hills.

Why did not the Boers make an onslaught on the town after the fight at

Rietfontein—why did not they do so after Nicholson's Nek?—or failing

this, why did they besiege Ladysmith? Why did they not leave an opening

on the south for the English to retire by?

Such questions have been repeatedly put after all was past, and it was

seen what might have been done. But the people who put these questions

assume circumstances which did not exist. For instance, it was

altogether impossible in the as yet unorganised state of the commandos

of the two States to venture on a united assault on Ladysmith, after

either Rietfontein or Nicholson's Nek. And it is quite dubious whether

the English wished to retire southwards. In fact the contrary appears to

be the case, for they might have evacuated the town, if they had wished,

before the 2nd of November,—eight days after Rietfontein,—on which

date the Boers had completed the investment of the town. The British

had, in point of fact, during those eight days not only shown no signs

of any desire to leave the town, but they had made a sortie, which had

resulted in the fiasco at Nicholson's Nek on the 30th of November.

(p. 17) It appears thus, when everything is taken into consideration,

that no General would have acted otherwise than General Joubert did; and

nobody, indeed, did think, during the siege of Ladysmith, that it was a

mistake to be doing so. It was only later that all manner of mistakes

were discovered in the besieging of Ladysmith, and not only of

Ladysmith, but also of Mafeking and Kimberley.

The town was besieged. That is a fact. I have only to do with that

fact now, and I am going to relate how the Free State commandos did

their part of the work.

On the day after Nicholson's Nek, certain Free State Commandants were

told by General A. P. Cronje, who had arrived on the 24th October and

assumed his command, to march their burghers to the south of Ladysmith,

and take up positions somewhere near or on the farm, Fouries Kraal.

These burghers consisted of portions of the commandos of Harrismith,

under Commandant C. J. de Villiers; Vrede, Commandant Anthony Lombaard;

and Heilbron, Commandant L. Steenekamp. General Cronje was in command of

the whole force.

Mr. Jan Wessels of Harrismith was appointed as guide, and the force

began to move as soon as it got dark. This was my first experience of

about a hundred night marches in which I took part during the war, and I

must confess that it was one of the worst I was ever in. I learned to

know the Africander in one of his weak points—his impatience of

discipline. I saw how he rebelled against what was the legitimate

authority under which he should have submitted.—How different it became

later in the war! As I write now nearly three years have passed since

that night march, and if I compare it with the night trek, for instance,

of the 23rd of February 1902 (of which I shall give an account later),

it is well-nigh impossible to believe that the strong, obedient (p. 18)

burgher of 1902 is the same man as the almost unbridled one of the end

of 1899.

Everything was in chaotic confusion. One would have imagined that the

burghers stood under no orders whatever, and yet orders had been issued.

They were openly disregarded. It had been ordered, for instance, that

there should be no smoking, and yet all along the route—we were going

from the rear to the van—little flashes of light could be seen of

matches, with which the men lighted their pipes. Nobody bothered his

head about the question as to whether these lights could show our

whereabouts to the enemy. Then the men had been told to proceed in

absolute silence, and yet there was not even an attempt to do so.

Besides a dreadful din which was raised by the drivers of the mules that

were inspanned in the gun-carriages, the burghers conversed quite

loudly, cracked jokes, and laughed in explosive guffaws—for all the

world as if they were on some errand which involved no danger. In my

immediate vicinity there was a young burgher of the name of Adriaan

Venter—he was nicknamed Dapperman because of his gallant behaviour at

Rietfontein. Well, this young fellow never wearied of saying funny

things; and I heard him use now for the first time his favourite

expression, "Jij is laat" (you are too late). This expression was soon

adopted by everybody in the field, and was used whenever anybody had

missed what he had had in view. Dapperman kept himself and all about him

in the best of spirits from the beginning to the end of that night

march, and it never entered his mind that scouts of the enemy might be a

hundred yards from us. Nothing struck me more than the entire

thoughtlessness of the burghers.

Just after we had begun to march, the clouds lowered, and it became very

dark. We could not see one another. The jokes of Dapperman only told me

that he was still near. Then it began to rain, and (p. 19) the road

became slippery. We progressed more and more slowly until at length we

almost came to a standstill. This was caused through the difficulty

which was encountered in taking the cannons through Sand River. The road

at the drift had become so slippery that it was next to impossible for

the mules to stand.

And meanwhile the darkness became thicker. I wondered whether I should

be able to see my hand if I held it before my eyes. Yes I could, so what

had been said of darkness so dense that you could not see your hand

before your eyes was not applicable here. Still, it was so dark that you

could not see the man you touched next you.

How provoking our slow progress was. We went twenty yards, and then we

halted for five or ten minutes. Then off we went again, and came to a

dead stop after we had progressed not more than twenty or twenty-five

yards. What were they doing in front, we were wondering; and the answer

came: "The guns can't get on."

Thus it went on until midnight. The General saw then that he could not

proceed, and ordered us to stop. We halted just where we were on either

side of the road we were travelling along.

Did the English know anything about us? I asked myself. There was

nothing to prevent it. Not only was it so dark that English scouts could

have been moving about among us, but we had shown them where we were

with our matches, and the noise we had made had revealed the direction

of our march. What, thought I, if they sent a shower of shells on us as

soon as it became light But this did not happen. The enemy had not yet

recovered from what they had suffered at Nicholson's Nek, and a few days

would elapse before a sortie from Ladysmith was again undertaken.

The morning broke dark and damp. Clouds hung (p. 20) low in the sky and

it looked like rain. This was not encouraging. Nor was it encouraging

when we saw how little we had got on in the night. We were not more than

two or three miles from where we had begun. But we had to go on

now—daylight or not, whether we were seen or not.

The whole force came into motion. It was a beautiful sight to see the

commandos together. I looked back from the van. The force was riding

over a great level space. There were at least two thousand together. An

insignificant number—but for us, the troops of two poor little

republics, it was large.

The clouds did not deceive us. We had hardly begun to march when several

heavy showers fell, and the prospect of a wet day was not pleasant. But

to the relief of all the weather cleared up before nine o'clock, and the

beautiful spring day followed: one of those days of unclouded sky which

are so rousing and vivifying in South Africa. After a short morning trek

we halted for breakfast, and then continued our march.

And now it began to be interesting.

A small body of Harrismith burghers had been told off to ride some miles

in advance, while the main body came on behind. Nobody could know what

might happen behind the ridges and kopjes which we were constantly

approaching and passing. The utmost care was observed. We halted

frequently until from time to time the reconnaissance of the country in

front was satisfactorily completed. Now and then we saw living objects

in the distance, and we could not know, of course, whether they were not

scouts of the enemy; but after Marthinus Potgieter had observed the

ridge or kopje through his long telescope and declared that the figures

were Kaffir women, and after our scouts had passed without adventure,

we knew that all was well, and went on.

(p. 21) We arrived at the house of an English missionary about twelve

o'clock, and Commandant de Villiers turned aside to see him. The

missionary showed signs of anxiety, and seemed to fear that harm would

be done to him. Commandant de Villiers assured him that nothing would

happen, if he put a white flag on the gable of his house as a sign that

he was a non-combatant. I accompanied the Commandant, and enjoyed a cup

of tea which the good wife of the missionary gave us. While we were

drinking the tea I heard children's voices in another part of the house,

and I was affected by them. A child always touches what is most tender

in me. And here I remember that I was especially moved by the sharp

contrast between those sweet children's voices and the harsh voices

which I had heard during the last few days of men talking about nothing

but the war.

We hastened forward, and had scarcely reached the main body when we saw

in the distance some of our scouts galloping back. Field-Cornet Jan Lyon

thereupon set spurs to his horse, and dashed forward with a small body

of burghers. Soon we learned that, while a portion of our scouts were

proceeding along a cutting near Onderbroek Spruit, they were fired upon

by some Irish Fusiliers, who had concealed themselves behind huge

boulders on the roadside. Isaac du Plessis was wounded in the thigh. The

other portion of our advance party had gone over the hill, west of the

road, and had fired on the Irish Fusiliers, with the result that they

were driven off.

Isaac du Plessis was my first case. I bandaged him as well as I could,

and he was sent away for proper medical treatment.

We passed by the spot where the incident had occurred, and I saw the

corpse of a soldier lying on the roadside. He had been shot by our men

from the hill. He lay on his back, and had been covered (p. 22) by our

burghers with grass. How well I remember the emotion that passed through

me when I saw there for the first time the corpse of a man killed in

action. How many it would be my lot to see and—bury.

Nothing further happened, until we arrived late in the afternoon at a

spot on the high ranges of hills between Colenso and Ladysmith, about

three miles east of the main road. I went with two others over the

range, and they pointed out to me the tents of the English garrison, on

the left bank of the Tugela, near the village of Colenso. The view was

grand. A vast plain lay stretched out before us, and through it the

greatest river of Natal was cutting its way, and swiftly descending to a

series of rapids and falls into precipitous abysses. We stayed and

looked upon the great scene until the fast falling shades of night

warned us to return to the laager. Soon we were wrapped in deep and

restoring sleep, for we were very tired.

(p. 23) CHAPTER III

BESIEGERS AND BESIEGED

Ladysmith was now completely surrounded. It was besieged on the north

and east by the Transvaal and on the west and south by the Free State

commandos.

Early on the morning after we had marched to the south—on 2nd

November—Field-Cornet Jan Lyon went with a body of men to Pieter's

Station, broke up the rails there, and took the telegraph clerk

prisoner. While he was doing this the two guns which we had brought with

us were being dragged up the range of hills between Ladysmith and

Colenso. One of them was put on the summit of a pointed hill a little

south of Platrand (Cæsar's Hill),—the other on the heights north of

Colenso. I was present when Commandant de Villiers drew the latter up

the precipitous slopes. There were huge boulders, as high as the wheels

of a waggon, thickly strewn on the hillside, and over them the Krupp had

to go. A strong span of oxen was put before the gun, and one could hear

the creaking of the yokes as the oxen strained to draw the gun up, but

as it became steeper and steeper it soon appeared that even the

South-African ox had a task which it could not do. The wheels of the

gun-carriage got jammed between the boulders and remained immovable.

Then the burghers took the work in hand, and what ox-power could not

do, human muscles accomplished. Some (p. 24) of the men seized the yokes

and the trektouw,[1] and others put their shoulders to the wheel, and

up flew the gun. It was not long before the Krupp made itself heard. To

the English fort near Colenso it sent a few shells—but the garrison

there had fled.

The Winburg Commando was encamped a little more to the north-east than

we were, and had an early surprise. While they were engaged in broiling

meat for breakfast there were heard in sharp succession the reports of

guns, and immediately several shells fell right in their midst. It is

needless to say that there was a confused scramble in search of cover;

but fortunately nobody was hurt. The enemy, having given an exhibition

of their gun practice, retired immediately to Ladysmith.

The next day General A. P. Cronje sent 900 men chosen from all the

commandos to take a ridge south-west of Ladysmith, not far from the

house of Mr. Willem Bester, in order to oppose the enemy, who had made a

sortie from Ladysmith in considerable numbers, on the road leading to

Colenso.

From this ridge the burghers opened a steady fire on the approaching

English, who were also subjected to a heavy and continuous bombardment.

This went on for a considerable time, and then a number of mounted

troops charged the ridge, but were repulsed. After that others rode into

a donga to the west of our positions, and leaving their horses in it,

emerged with the object of taking possession of a low reef of rock

between themselves and us. But here, too, they were unsuccessful. Our

men opened such a withering fire on them that they were obliged to

abandon their design.

At this moment about 150 of the enemy gained possession of a hill to the

south with the object of surrounding us by the east. Sixty Winburg and

Harrismith burghers seeing this, charged them; but (p. 25) the bullets

of the English fell so thickly on them that forty of them turned back,

so that only twenty reached the top. There, however, they found

themselves in such a terrific fire that they could do nothing, and were

obliged to seek cover behind large boulders. Such was the state of

things when our Krupp on the pointed hill sent a well-aimed shell among

the English, and at once changed matters. The shell was followed without

delay by another, and when the fourth came the enemy was compelled to

retire. Then it was our opportunity. The twenty burghers emerged from

their hiding-places and fired upon the retiring English, and the hill

was quickly cleared.

While this was going on I was with the Harrismith Commando, which was

madly galloping as a reinforcement to the fight. We had to pass a spot

where shots occasionally fell, and as we raced along there, I heard for

the first time in my life the whiz of a passing bullet. We went on, and

arrived on the hill. But all was just then over, and we could only see

the English retreating to Ladysmith. Twice or thrice yet they fired

shrapnels at us, and again I had a first experience. It was of the

sound, sharp and shrill, of a shrapnel that went over our heads. I don't

know in what other words it can be described.

What a tyranny fear is! At the foot of the hill I saw a young burgher,

utterly overpowered by it, lying behind a large stone and not daring to

raise his head.

"Are you wounded?" somebody asked him.

"No," answered the terror-stricken youth, and pressed still closer to

the stone.

I met Mr. Roux here again, and assisted him to bandage the burgher

Gibson, who had been badly wounded in the leg. Two others also were

wounded.

Nothing further happened now, and in the evening we were in our little

field tents again.

During the following three days there was an (p. 26) armistice in order

to enable the enemy to get their women, children, and non-combatants out

of Ladysmith into the Intombi Camp, between the town and Bulwana.

On Sunday, the 5th of November, our commando went to Pieter's Station. I

had preached early in the morning for the burghers of Vrede; and now,

after we had inspected the station, we gathered under a great camel

tree, and had a most pleasant service. Just before the service some

burghers slipped away unobserved and sped to Colenso. Arrived there,

they helped themselves to what they fancied they needed in the shops.

While they were thus engaged, an armoured train came from Chieveley, and

began to fire on them.

We were lying unconcerned in the shadow of the great camel tree, when

Commandant de Villiers got the report that some burghers were hemmed in

at Colenso. He immediately gave orders that the horses should be saddled

and rode thither, but we heard on the way that the culprits had, by the

skin of their teeth, made their escape under a shower of bullets.

When we were returning to our laager, we met Kaffirs who had fled from

Ladysmith. They drew a terrible picture of the state of the town. They

told us that there were still unburied soldiers there, and that a bad

smell pervaded the town. Women and children too had to endure great

suffering, and were obliged to hide in holes which had been scooped out

in the river's bank.

We did not know then that we had to take Kaffir reports with a grain of

salt.

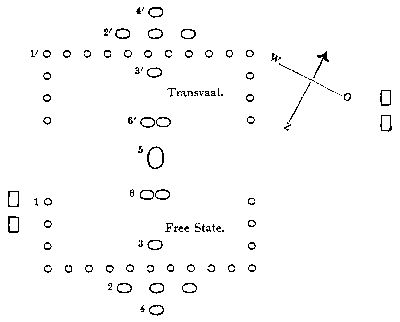

Towards the 10th of November the Free State laagers lay around Ladysmith

in this order: Near the railway line to the east of Smith's Crossing was

the laager of the Kroonstad Commando. To the west of the line, General

Prinsloo had fixed his headquarters; (p. 27) and thence round to the

south stood in succession the laagers of the Bethlehem, Vrede, Heilbron,

Harrismith, and Winburg Commandos. Each Commandant had one or two guns.

Commandant de Villiers had charge of two. For these he built forts on

the hill upon which the 150 English were shelled in the fight of the 3rd

of November. This hill lay to the west of Mr. Bester's house.

We Harrismith burghers pitched our camp at several places, but at last

we fixed it permanently at the south-west of this hill. From the forts

on the top of the hill you can see close at hand in the direction of

Ladysmith the Neutral Kopje. Right before you in the depth you see the

house of Mr. Bester, and there on the other side of the kloof rises

Platrand, or Cæsar's Hill, on which the English are making forts and

sangars. Every now and then you see a cloud of smoke from our

cannon-forts, and a Krupp sends a shell on Platrand, to which the

English with splendid aim promptly reply. From every side and every

schanz the forts of the English were bombarded. The big gun of the

Transvaalers on Bulwana, to which the British gave the name of Long Tom,

was especially active, and sent its great shells regularly every day

into the town.

And now we were living in the constant expectation that Ladysmith would

speedily fall into our hands. Our expectations were also constantly

strengthened by Kaffir reports. There was, the Kaffirs told us, very

little food in the town, and the distress was great. Week after week,

therefore, we were expecting that Ladysmith would capitulate, but week

after week Ladysmith held out.

On the 14th of November another fight took place. The English made a

sortie to the south-west of the town, and attacked a position where

there were eighty men of the Vrede Commando. They opened a heavy

cannonade on the rand and made it almost untenable (p. 28) for the

burghers there. Then our guns came to the rescue. The two Harrismith

Krupps fired on the rear of the enemy. Others assisted, and everything

was managed so effectively that the English had to retire precipitously.

A man came to our laager in the evening and told us that he was in the

Vrede position while it was being shelled. It had been terrible, he

said. One poor fellow, a young burgher of the name of De Jager, had been

hit in four places, while lying behind a boulder, by a shrapnel—three

bullets had struck him in the shoulders and one in the head, and he had

died immediately. Two others were slightly wounded.

Our laager had not been out of danger. A piece of a shell had fallen in

it. Afterwards this happened frequently. Bits of missiles sent from

Platrand to the cannon-forts above now and again came into our camp, to

the great amusement of those who did not happen to be in danger at the

moment. How funny it was to see the men near the spot scramble to cover

when the danger was past.

About this time the Bethlehem Commando made a large capture of cattle.

Some Coolies were taken prisoners on the occasion. Everybody naturally

besieged the prisoners to hear something about Ladysmith. The wily

Indians took in the situation at once, and told us what they knew would

be agreeable to us. They "spoke comfortably to our hearts," and depicted

the condition of the town in the most appalling colours.

Just at this time too—on the 15th of November—Commandant-General

Joubert sent, under the command of General L. Botha, 1600 Transvaalers

and 500 Free Staters to Estcourt. Some of them came into action with an

armoured train near Chieveley. From the train a vigorous fire was opened

on the Transvaalers, who replied with cannon and rifle. Some Free State

burghers were in advance and (p. 29) attempted to break up the railway.

But as they had no tools to do this with, they could not, and instead

raised the rails on one side and placed big stones underneath. The train

then steamed back and two trucks were derailed. Immediately, under a

heavy fire from us, the English set to work to remove the stones, and

then the engine went backwards and forwards and came with every forward

motion into collision with the trucks. It succeeded soon in removing the

impediment, and sped away with the trucks which had not been derailed.

Fifty-six troops and three civilians were taken prisoners. Among these

was Mr. Winston Churchill, who escaped later in a very clever manner

from the Model School at Pretoria, in which he was being kept confined

as a prisoner of war.

We heard of this affair with the armoured train while we were chatting

in very rainy weather in the tent of Commandant de Villiers. It was

dripping wet outside and the laager had been converted into a perfect

puddle of mud by hundreds of feet. General J. B. Wessels and Commandant

Theunissen of the Winburg Commando were there on a visit. We were

talking about the armoured train, and presently General Wessels related

that a man had been taken prisoner the day before by the Winburg

burghers. This man had been found in a Kaffir hut, and had with him a

basket of pigeons, which he had brought from Maritzburg to smuggle into

Ladysmith. But as Dapperman said, "He was too late."

It did rain that day! and in the evening a steady downpour set in. I

sympathised with the sentries and outposts, who had to take duty on the

top and the slopes of the hill. What a cheerless thing it was, I

thought, to sit through the livelong dripping night with no shelter, and

to gaze into the darkness.

I can give no account of the adventures of the expedition which General

Joubert sent to Estcourt, (p. 30) as I did not accompany it. I can only

say that the burghers composing it did not remain long south of the

Tugela, and were obliged by great numbers of troops to return to

Ladysmith. General Joubert, however, said that he had succeeded in his

object of preventing all the English troops from massing on the western

borders of the Free State.

Shortly before the expedition was sent to Estcourt, the portions of the

several commandos which had been left on the Drakensberg were ordered to

descend into Natal and join the besiegers of Ladysmith. They arrived in

due time, and brought all the waggons with them. We had after that the

convenience of a laager. Tents of every shape and size soon sprang up

everywhere between the great waggons, and nobody who was not actually on

duty needed to have any apprehension with regard to heat, or cold, or

wet. There were indeed several who had raised their voices against the

bringing down of the waggons, and had said that they would prove to be

an encumbrance, in case a hasty retreat became necessary, but the

majority of the burghers were bent upon taking it easy—even in the

war—and demanded that the waggons should be brought down.

As far as I was concerned, though I did not approve of the presence of

the waggons, it was a personal pleasure to have a large square tent with

a table in it. Writing on a table was a decided improvement to writing

on a book, or a pad, on one's knees, or on the ground.

That tent in which I wrote!—how I remember it, while I am in Cape Town

writing my book over again.

The time passed swiftly, though it dragged from moment to moment. This

was one of the first things that struck me in the war. I would wake in

the morning and feel the duty of the day lying on me, as a burden which

could not be lifted. But when the (p. 31) shadows of night had fallen I

found that the burden had been borne. It often seemed as if the future

lay far beyond my reach, but after an hour, a day, a month was past, the

hours seemed to be seconds, the days hours, and the months weeks.

The burghers were terribly bored in the laager? Why? They wanted

nothing. The Government provided meat, bread (in the shape of meal),

coffee, sugar, potatoes,—sometimes tobacco;—we even lived in luxury,

for our wives sent us fruit and vegetables, cake and sweets. Why, then,

did the burghers feel bored in the laager?

The reason is that the Africander is not a soldier, who can take kindly

to camp or barrack life. The Boer detests a confined life, and whenever

he is away from the open plain, and the free breezes of heaven, he is

miserable. Thus it was that every burgher now longed to be back on his

farm.

How I pitied the Commandant! He was continually besieged by burghers

asking leave to go home. They asked for leave on the slightest pretexts,

or with no pretext whatever; for they would give as a reason for leave

of absence the work which had to be done on the farms. The women looked

after that as well as, and in many cases better than, the men themselves

had done. No, in the majority of cases there was no sound excuse to

justify a request for leave. It was simply because they could not stand

the confinement of the life in a laager.

Towards the end of the third week in November, one of the heavy guns of

the Transvaal—another Long Tom—was brought into the Harrismith laager

in order to be placed on the hill where our two guns stood. What a

monster it was!

A wooden platform of thick deal beams was constructed in the fort, and

Long Tom was drawn into position during the night. On the following

morning it fired on the forts at Platrand (Cæsar's Hill), and (p. 32)

the terrific recoil splintered the stout beams of the platform as if

they had been thin lathes. The platform had to be rebuilt and rendered

stronger.

While we were doing this, the English were not idle. They were busy

putting a heavy gun on Platrand into position; and on the following day

they sent shell after shell, which pulverised the rocks and ploughed the

ground, but which happily did no injury to Long Tom.

On Sunday, 26th November, I visited the Bethlehem laager with the

intention of holding divine service there. On arriving, I found

everything in a state of hurry and bustle. Here someone was roasting

coffee, there another was shoeing his horse, yonder a third was greasing

the axles of his waggon. The cause of all this activity was that the

commando had been ordered to the western border by the War Commission,

and that they were preparing to start.

I succeeded in my intention of addressing the burghers, and took as my

text the comforting words of St. Paul: "Be of good cheer: for I trust in

God, that it shall be even as it was told me."

A fortnight afterwards, Acting-Commandant Christian de Wet was appointed

General, and likewise ordered to the western border. His achievement at

Nicholson's Nek had fixed the attention of the War Commission on him,

and he was now called to take upon himself the rank and important duties

of a General. I had no suspicion then that Christian de Wet had begun

the career which would make him famous throughout South Africa; nay,

throughout the world!

Thus far we had busied ourselves exclusively with the enemy hemmed in at

Ladysmith; but on the 28th of November the Boers were also threatened

from the south of the Tugela. On that day a considerable number of

troops advanced from the direction of Chieveley, and opened a heavy

fire on (p. 33) the Boer positions north of the river, with about twelve

guns. The Boers replied, and our shells fell upon the British until they

were forced to retire.

Platrand! What enchantment hung over that hill! From the first moment

that we had come south of Ladysmith, it had been the talk of everyone

that the hill should be taken; and about a week after the investment of

the town, Commandant de Villiers had actually made a night march with

the object of making an assault on it; but General Joubert had recalled

him before he could begin the attack. Since then the cry had ever been:

"The hill must be taken!" At last, wearied of the continual nagging, the

combined War Council of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State decided

that 900 men should storm the hill during the night of the 29th-30th of

November.

Many considered the decision unwise. They were of opinion that the hill

could not be taken without great loss of life, and that it was doubtful,

after it was taken, whether it could be held. Nobody, however, opposed,

and preparations were made to set out at two o'clock on the 30th of

November.

Something, however, intervened.

At ten o'clock in the evening some Transvaal officers entered the tent

of Commandant de Villiers, and pointed out that there was no shelter for

the storming party, and that the dongas at the foot of the hill, instead

of affording shelter, would prove disadvantageous to us in case we were

forced to retire. One officer after another entered the tent until there

were fifteen together, and all were opposed to the project of storming

the place. At one o'clock they had convinced one another that Platrand

could not be taken, and took it upon themselves to disobey the orders of

the Council of War, and so far from storming Platrand at two o'clock,

everyone was sound (p. 34) asleep in his bed at that hour. The evil day

was postponed.

On 7th December my son Charlie, aged 15, arrived in the laager. I had

left him behind at Harrismith to go to school, but it was impossible to

keep him there, and he had come to the laager at the first opportunity,

after receiving my consent. When he had been with me but a short while

he got a Lee-Metford from his friend Jan Cilliers, which had been taken

at Dundee.

At this time it became clearer and clearer that some event or other

might with certainty be expected from the south. The British

Commander-in-Chief in Natal, General Buller, had been there for some

weeks, and had had plenty of time to prepare himself. There was no doubt

that he had been busy, for more and more troops had come from Durban,

until the camps at Chieveley had grown to amazingly large proportions.

Everyone then was expecting that something was going to happen soon.

But in the meanwhile something took place closer to us, which filled us

with shame and indignation. In the night of the 7th-8th of December a

number of English climbed Lombard's Kop, where the heavy gun of the

Transvaalers was. They approached the fort in the greatest silence, but

the picquet became aware of their approach and cried, "Werda?"

Someone answered in good Dutch, "Don't shoot. We are the Modderspruit

burghers."

This satisfied the picquet, and the next moment the enemy was in the

fort.

Our men were taken by surprise, but they fired notwithstanding, and a

few English were wounded.

The few men in the fort were now forced to yield, and retreated before

overwhelming odds. Then the British damaged Long Tom so seriously that

it could not be used again for fifteen days. They also (p. 35)

partially destroyed a French quick-firing gun and captured a Maxim.

That same night another party of English damaged the railway bridge at

Waschbank (near Dundee) in such a manner as to stop the running of

trains for some days.

These two exploits of the English roused a feeling of dissatisfaction in

the minds of the burghers. They considered it a dishonour to us, and

although there were rumours of treachery, the general opinion was that

it was rather the carelessness and want of vigilance on our side that

was to blame. Everyone, on the contrary, meted out unlimited praise to

the English, and said that they had done a gallant thing.

Two days after it was Sunday, and I held divine services in different

places, according to my custom. On the same day, the Free Staters

captured a Kaffir, who had brought letters, sewn under the lining of his

sleeve, out of Ladysmith.

Those letters! How thoughtlessly they were read. Who cared that they

were the utterances of the heart, even though the heart of an enemy?

Who, whilst reading them, asked of himself: "What would I desire the

enemy to do, if a letter of mine should fall into their hands?" These

letters were from soldiers and civilians, mostly from husband to wife,

or from wife to husband. They bore witness to a very miserable state of

things in Ladysmith. One woman wrote that she lacked the common

necessaries of life; another that she went barefoot. Besides private

letters there was a report announcing that the troops were reduced to

half rations, and that many of them were sick; and also that an unknown

disease had broken out amongst the cattle.

Every day something happened, and the time passed rapidly. Was it not

because there was always something to keep us busy? Yes, a thousand acts

were crowded into each day.

(p. 36) The heart was filled with ever-changing emotions by the various

occurrences of each day. And one's mind was not occupied by the war

only. No! One's thoughts were drawn away irresistibly by the blue

expanse overhead, and by the wondrous landscape around, stretching away

to the finest horizons on earth. We lived in God's free nature, and as

we came nearer to her great heart throbbing in the grey veld and the

blue mountain, those of us who could felt ourselves borne away by a

delicious but withal terrible Power. How glorious, too, were the

evenings! How soothing was their deep silence after the exhausting,

bustling summer's day! And then there was the breath of air from the

east, which softly fanned the cheek, and calmed and laid to rest the

turbulent passions that rent the breast.

I used to sit of an evening beneath the camel thorn-tree, under which

Commandant de Villiers had pitched his tent, and gaze into the far west.

There lay Spion Kop, tinted pink by the last rays of the setting sun.

Far beyond rose the Drakensberg mountains with their rugged, dizzy

crags, scored and scarred, already veiled in the shadows of night. What

a thrill quivered through me when I presently looked up from that dark

mass and saw the glittering gold, which had been laid for a moment on

the clouds; or when, after the sun had set, turning, I beheld in the

east the wonderful maze of colour in the sky. The soft pink merged into

almost black purple, and this again, as if in need of support, rested on

the blue black rock foundation of the earth.

I forgot in such moments that we were at war. I was deaf to the

discordant sounds of the strife—the bursting of shells, and the whiz of

bullets. It was as if I heard God speaking in the still small voice.

Can I ever forget those evenings? I am living them over again. I still

gaze into that distant west, and seem to see the Unseen in that

wonderful vision: (p. 37) God, the Incomprehensible, the Unsearchable. I

see how He paints every evening a new picture on the mountains and on

the clouds. But He hides Himself in His picture. It is the robe, indeed,

in which He reveals Himself, but it is only the border, as Isaiah says,

the border of His robe: only the hem of His garment, and it—fills the

Temple!

(p. 38) CHAPTER IV

GENERAL BULLER'S FIRST GREAT ATTEMPT TO BREAK THROUGH

Since the beginning of November we had heard, as I have already said,

that Sir Redvers Buller had landed at Cape Town, and that he was in

supreme command of the troops in Natal. We also knew that he was busy

preparing himself for a grand attack upon our forces around Ladysmith,

in order thus to relieve Sir George White there.

Towards the end of November General Joubert received reports every day

of how matters were proceeding south of the Tugela. It was reported to

him that large numbers of troops were continually arriving from Durban,

and were occupying immense camps at Chieveley. Now, as it was impossible

to know exactly where General Buller would try to break through, it was

necessary to place commandos up and down the Tugela, with Colenso as a

centre. This was done. Various Transvaal commandos took possession of

the ridges opposite Colenso, and others were sent to the east of the

railway across the river to Klangwane, a wooded hill a few miles east of

the village, while General A. P. Cronje with from 1500 to 2000 men

trekked about twelve miles to the west.

I will here mention the names of the Transvaal commandos that occupied

the ridges opposite Colenso, because it was by them that the attack of

General Buller was repulsed. They consisted, to begin with the (p. 39)

most easterly wing, of a portion of the Krugersdorp Commando; next to

them were in succession westward the burghers of Heidelberg, Boksburg,

Johannesburg, the Swazieland Police; the Ermelo burghers and the

Zoutpansberg Commando on the wing farthest west.

These men worked night and day digging trenches and throwing up

earthworks. They did not make these works on the top of the mountain

range, where one would have expected them to, but on low ridges close to

the river. The enemy would thus, in case they attacked, first bombard

the wrong places, and the troops would approach to within a very short

distance of the position, and be subjected to a severe rifle fire,

before they knew from whence they were being fired on.

The first days of December passed by, and although there was no attack,

there were, however, signs every day to show that the English were

making preparations, and all held themselves in readiness.

Two or three days before the 15th of December one of the Transvaal

gunners, an Englishman, deserted, and as there was reason to fear that

he might acquaint the enemy with the preparations that had been made to

repulse an attack, General Louis Botha changed the positions of the guns

and also made the men dig other trenches and throw up new earthworks.

These trenches were dug on the level ground between the ridges I have

mentioned above and the river. If the former trenches were made where

the enemy would not expect them, this was still the case with the new

ones which were now made, as the result proved.

On the 14th of December Commandant de Villiers rode in the direction of

Colenso to see if he could discover any new developments in the

preparations of the enemy. He came to the top of the high hill between

Colenso and the Boer laagers around Ladysmith, (p. 40) and saw from

there that the British troops were approaching nearer and nearer to the

village. He computed them at about 10,000. "To-morrow," he said, on his

return to the laager, "there will certainly be a battle"; and he asked

me if I wished to go to the hill on the following day, in order to see

what might take place. I answered that I would like to go. Early on the

following morning, December 15th, we heard the roar of the great naval

guns. Commandant de Villiers had not been mistaken. The battle had

commenced.

I had my horse saddled and rode to the hill with a few burghers. There

lay the tiny hamlet of Colenso about five thousand yards from where we

stood, and down below with great curves the majestic Tugela flowed

onward, calmly and placidly. But there was no calm on its banks. The

ground shook with the thunder and reverberation of the great naval guns.

Everywhere, on both sides of the river, upon Boer and Briton, the shells

burst and the shrapnels exploded. Far away on the horizon seven or eight

miles from us, a little to the west of the railway, I saw the great

camps, looking like plantations of black-wattle trees, from which the

troops had marched that morning. About two miles on this side of the

camps, the batteries of British field-guns stood in an irregular

semicircle, and in front of these the whole plain, for about three miles

to the west of the railway and a mile and a half to the east of it, was

covered with troops; not in compact masses, but widely scattered.

I also saw ambulance waggons riding to and fro. When the cannons fired,

no volumes of smoke rose in the air as was the case with our Krupps, so

if one looked for smoke as a sign that a gun was fired, one would never

know that a shell had been despatched. But even in the broad glare of

the day you could constantly see a small flash, and presently a

terrific crash (p. 41) somewhere on our positions would proclaim that a

great naval gun had been fired. Our projectiles too were aimed at the

troops and guns down in the plain. I could continually see our shrapnels

exploding there. And the tiny shells of our Maxim-Nordenfeldts created

havoc among the troops; while thousands of little clouds of dust, like

those which rise when the first great raindrops of a thunderstorm fall

on a dusty road, showed where the Mauser bullets fell.

The scene constantly changed.

What also struck me was, that the hundreds of small objects which I saw

down there were continually appearing and disappearing. I could not at

first understand what this meant; but I soon perceived that when the

objects seemed to rise from nowhere it meant that the soldiers were

making some dash or other to a certain spot, and when they disappeared

it meant that they were forced to lie down because of a destructive hail

of bullets which was poured upon them. This was the state of affairs

when I reached the top of the hill.

I must now relate something of what had taken place up to that moment.

General Buller had ordered four brigades of troops early that morning to

make an attack on us, supported by great naval and other cannon, with

the purpose of breaking through our lines and forcing a way to

Ladysmith. The troops had hardly commenced their advance before General

Botha perceived it, and ordered that all the men's horses without

exception should be taken away from the positions. He also issued a

strict command that no one should fire a shot before he gave the signal

by the firing of a cannon from one of the ridges behind the burghers.

Our burghers lay behind their schanzes and awaited the enemy.

It was hardly daylight when they saw the English advance—covering a

breadth of nearly eight miles—the one wing about four miles west of

Colenso, and (p. 42) the other about three miles to the east. Presently

the British cannon opened a tremendous fire on the ridges behind the

burghers and the shrapnel burst everywhere with terrific sound. The

noise was deafening, but our men did not answer. The English advanced,

the flanks approaching nearer and nearer to the centre, and there were

some of our officers who sent word to General Botha, beseeching him to

give the order to fire. No. He let the English come nearer and nearer.

Not a Boer could they see. Nearer and nearer the troops advanced. They

became over confident. The Boers had certainly fled and left the road to

Ladysmith open.

Suddenly General Botha gave the command. The cannon thundered forth the

signal, and a fearful storm of lead fell upon the over-confident

soldiers. They had not expected it, and the shock was terrible.

Nevertheless they advanced, and continued pressing forward, only to be

mown down by the withering fire of our Mausers.

In the meanwhile they had discovered where our burghers were, and a

fierce cannonade was directed on them, which, however, wonderful to

relate, did hardly any damage.

At last the troops ceased to advance on the west wing. It was then that

I arrived on the hill. But in the centre attempts were still being made

to break through, and in endeavouring to do this, they approached so

near to the Boer positions, a little to the east of the railway line,

that they could fire on the bodyguard of General Botha and on the

Krugersdorp Commando from a distance of not more than eight hundred

yards. Our men opened a terrible rifle fire on the gunners, and in a

moment all was quiet. Not a single cannon there fired another shot.

The English perceived that they had brought twelve guns to a spot from

whence they could not get them away again. Notwithstanding this they

(p. 43) rushed in to save the guns. From the hill above I saw how the

matter went, and I do not think that a more heroic deed was done in the

whole war than the rush of the English to save those guns.

It was a magnificent sight!

Team after team of horses I saw galloping in the same direction. I saw

how mercilessly they were mown down by the bullets of our Mausers and

the shells of our Maxim-Nordenfeldts. I saw how they persevered in their

efforts, till at last they ceased their attempts.

I could not, at the moment, understand what it all meant, and thought

that the English were trying to take a position, whence they could rush

across the bridge, and it was only in the evening that I heard that this

splendid gallantry had been displayed in order to save the guns.

Two of the twelve guns were rescued, but the English could not get away

the rest. General Botha made this impossible when he sent men through

the river to fetch them. These men waded the stream breast high, and

took positions so near the guns that it became absolutely impossible for

the British to make any further attempts, and ten of the twelve guns

fell into our hands together with a number of soldiers who were there.

General Botha had been the soul of everything in this great battle. He

went from position to position encouraging his brave Transvaalers. Here

he would direct their fire, and there he would send reinforcements.

Everything was controlled by him.

Some days later I had a conversation with Colonel de Villebois, who had

also been present at the battle. He said to me: "General Botha is a true

General. I saw this during the battle of Colenso. If I discovered a weak

point in the Boer positions, General Botha had perceived it before me,

and was already busy strengthening it. He is a true General."

(p. 44) Shortly after midday all was over.

Sir Redvers Buller commanded that the troops should retire. His plan had

been a great one, his troops had fought bravely, but they had failed,

failed splendidly.

The Boers, on the other hand, had repulsed the terrible attack. But they

did not ascribe it to their own efforts; no. General Botha telegraphed

to his Government that evening: "The God of our fathers has given us a

brilliant victory."

Our loss was, incredible as it may seem, seven killed, of whom one was

drowned, and twenty wounded. There had not been more than 3000 men in

the positions from whence the British had been repulsed!

On the following day Dingaan's Day was celebrated in all the laagers

with excessive joy, as might be expected. The Africander nation

perceived a new proof of God's protecting hand in what had happened on

the previous day, and the future seemed bright.

On Monday, the 18th, I left for my home, in order to celebrate Christmas

and New Year with my family. I remained at Harrismith till the 4th of

January 1900.

(p. 45) CHAPTER V

PLATRAND

On Friday afternoon, the 5th of January 1900, I was back in the laager

of Commandant de Villiers once more.

In the evening I sent a letter to my wife in which inter alia these

words appeared: "And now I have no time to write anything more, but, as

the post leaves to-morrow, I wish you to know as soon as possible of my

safe arrival." I wrote nothing that could cause uneasiness, and yet

there was much that would have made her anxious if I had written about

it. Would this letter be the last I should write her? I asked of myself;

for we were on the eve of attacking Platrand (Waggon Hill).

As I have said in a former chapter, it had from time to time been

insisted on that Platrand, as being the key to Ladysmith, must be taken.

This had constantly been insisted on. General Prinsloo had declared that

the hill ought to be taken, and that he could do it with 100 men.

President Steyn had also telegraphed, saying that it was desirable to

have Platrand in our possession. Not a day passed without regret being

expressed that the rand had not been taken when, on former occasions,

attempts had been partially made, and now more than ever it was thought

that this should be done. This string had been so continuously harped

upon that the combined War Councils of the Transvaal and Free State

once more decided that an attempt to gain (p. 46) possession of Platrand

should be made. After I had held evening service for the first time

since my return, Commandant de Villiers made known to the burghers that

men from every commando would proceed to the hill that same night.

This famous hill, named Waggon Hill by the English, lies about three

miles south of Ladysmith, between the residence of Mr. Willem Bester and