RALPH IN THE SWITCH TOWER

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Ralph in the Switch Tower

Author: Allen Chapman

Release Date: March 04, 2012 [EBook #39051]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RALPH IN THE SWITCH TOWER ***

Produced by Al Haines.

CONTENTS

- CHAPTER I--DOWN AND OUT

- CHAPTER II--UP THE LADDER

- CHAPTER III--A CLOSE GRAZE

- CHAPTER IV--A MYSTERY

- CHAPTER V--THE STOWAWAY

- CHAPTER VI--MRS. FAIRBANKS' VISITOR

- CHAPTER VII--"YOUNG SLAVIN"

- CHAPTER VIII--A BAD LOT

- CHAPTER IX--CALCUTTA TOM

- CHAPTER X--A MILE A MINUTE

- CHAPTER XI--SPOILING FOR A FIGHT

- CHAPTER XII--THE SUPERINTENDENT'S OPINION

- CHAPTER XIII--SQUARING THINGS

- CHAPTER XIV--A BUSY EVENING

- CHAPTER XV--A HERO DESPITE HIMSELF

- CHAPTER XVI--KIDNAPPED

- CHAPTER XVII--A MIDNIGHT VISITOR

- CHAPTER XVIII--A DESPERATE CHANCE

- CHAPTER XIX--THE DOUBLE WRECK

- CHAPTER XX--THE CRAZY ORDERS

- CHAPTER XXI--IKE SLUMPS "NUTCRACKER"

- CHAPTER XXII--A HEADSTRONG FRIEND

- CHAPTER XXIII--IKE SLUMP & CO.

- CHAPTER XXIV--FIRE!

- CHAPTER XXV--THE LITTLE TIN BOX

- CHAPTER XXVI--A CLEW!

- CHAPTER XXVII--SLAVIN GETS A JOB

- CHAPTER XXVIII--WHAT THE "EXTRA" TOLD

- CHAPTER XXIX--GUESSING

- CHAPTER XXX--PRECIOUS FREIGHT

- CHAPTER XXXI--HALF A MILLION DOLLARS

- CHAPTER XXXII--CONCLUSION

CHAPTER I--DOWN AND OUT

"Get out of here!" said Jack Knight, head towerman of the Great Northern Railroad, at Stanley Junction.

"Why, I ain't doing no harm," retorted Mort Bemis, ex-leverman of the depot switch tower.

"And stay out. Hear me?" demanded Knight, big as a bear, and quite as gruff.

"What's the call for sitting down on a fellow this way, I'd like to know!" muttered Bemis sullenly.

"You're a bad lot, that's what," growled the veteran railroader. "You always were and you always will be. I'm through with you. So is the railroad company. What's the call, you meddlesome, malicious reprobate? That's the call!" fairly shouted the towerman, red of face and choleric of voice.

He moved one arm as he spoke. It hung in a sling, and the hand was swathed in bandages.

"There's some of your fine, Smart-Aleck work," he went on angrily. "Come now, take yourself out of here! This is a place for workers, not loafers."

Mort Bemis gave Jack Knight a revengeful look. Then he moved towards the trap in the floor.

The scene was the depot switch tower at Stanley Junction, in sight of the local passenger depot. It loomed up thirty feet in the air, glass-windowed on every side. It was neat, light, and airy. In its center, running nearly its length, was the row of long heavy levers that controlled the depot and siding switches of the terminus of the Great Northern Railroad.

The big-framed, business-faced man who bustled among these, keeping an angry eye meantime on an unwelcome visitor, was a veteran and a marvel in local railroad circles.

When the Great Northern had come to Stanley Junction, ten years back, it brought old Jack Knight with it,

He had an eye like an eagle and the muscles of a giant. The inside of his head was popularly believed to be a vast railroad map. He controlled the main rails, switches, and sidings, like a woman would the threads of an intricate knitting piece. He directed the locomotives and trains up and down that puzzling network of rails, like puppets moved by strings. In ten years' service he had never been responsible for an accident or a wreck.

Old Jack, therefore, having never made a mistake in railroading, had little patience with the careless, lazy specimen whom he had just ordered out of the place.

Mort Bemis had been his assistant in the tower. The fellow's record had always been full of flaws. He was slow and indifferent at the levers. He associated with a shiftless crowd outside. He borrowed money and did not pay it back. He was unreliable, disagreeable, and unpopular.

Three days previous, old Jack was adjusting a heavy weight bar on the lower story of the switch tower.

Mort, upstairs, was supposed to safely hold back a spring-bar apparatus while his superior was fixing the delicate mechanism below.

His mind everywhere except on his task, Mort for an instant took his hand off the bar to wave a recognition to a chosen chum, "flipping" a passing freight train.

There was a frightful yell below. Mort, terrified, pulled back the bar. Then he stuck his head through the trap. There stood old Jack, pale as death, one hand crushed and mutilated through his helper's outrageous lapse of duty.

The old railroader's rage was terrible, as he forgot his pain and hurt in the realization that for the first time in ten years he was crippled from active service.

The frightened Mort made a dive for a window. He slid down the water-spout outside, got to the nearest switch shanty, telephoned the depot master about the accident,--and made himself scarce.

Mort joined some chosen chums in one of the haunts of Railroad Street. He reported by 'phone "on the sick list" next morning. He did not show up until two days later, "after a good and easy rest," as he put it, and then fancying old Jack's "grouch" had cooled down.

Mort's reception has been related. He was informed that the railroad company had peremptorily discharged him. As to old Jack himself, Mort readily discerned that the veteran railroader was aching to give him a good hiding.

Mort did not wait to furnish an excuse for this. He now started down the trap-door ladder, grumbling and growling.

"Be careful!" rapidly but pleasantly warned someone whom Mort jostled a few feet from the bottom.

Mort edged over and dropped to the floor. He gave the speaker a keen look.

"Hello! Oh; it's you?" he muttered with a scowl; "Ralph Fairbanks."

The person addressed responded with a short nod. Then he continued to mount the ladder in an easy, agile way.

"Hold on," challenged Bemis.

He had planted his feet apart, and had fixed a fierce and malignant glance upon the newcomer.

Suspicion, disappointment, and rage showed plainly in his coarse, sullen face.

There was something in the striking contrast between himself and the other that galled Mort.

He was "down and out," he realized, while the neat, cheery, ambitious lad whom he had hailed, three years his junior, was "going up the ladder" in more ways than one.

The latter wore a new, clean working suit, and carried a dinner pail. He suggested the wholesome, energetic worker from top to toe.

"I am holding on," he observed to Mort, stopping half-way up the ladder.

"Thought you was working at the roundhouse?" said Mort.

"I was," answered Ralph Fairbanks. "I have been promoted."

"Where to?"

"Here."

"What!" flared out Mort. "What do you know about switch-tower duty?"

"Not much, only what Mr. Knight has shown me for the past two days. But I'll catch on, I guess."

Mort Bemis struck a tragic pose and his voice quavered.

"Oho! that's the game, eh? All cut and dried! My bread and butter taken away from me, to give to one of the master mechanic's pets. Augh!"

Mort retreated with a grimace of disgust. He was standing under a floor grating. Purposely or by accident, Knight, overhead, had dropped a dipperful of water through the grating.

Mort jumped outside the lower tower room, growling like a mad catamount. He shook his fist menacingly at Ralph.

"Fairbanks," he cried, "I'll fix you for this!"

Ralph did not even look at his enemy again. He completed his ascent of the ladder, and came up through the trap with a bright, cheery hail to old Jack, whom he liked and who liked him.

"I report for active duty, Mr. Knight," he announced briskly.

"Oh, do you?" retorted the old railroader, disguising his good nature under his usual mask of grimness. "Well, you're ahead of time fifteen minutes, so just sit down and behave yourself till I get those freights over yonder untangled. Anxious for work, are you?" he pursued quizzically. "You'll have enough of it. I'm ordered up to the crossings tower, and you'll have to take the first half-night shift here alone. Think you can manage it?"

"I can try, Mr. Knight," was the modest but resolute reply.

CHAPTER II--UP THE LADDER

Ralph Fairbanks was a full-fledged railroader, young as he was.

Those who have read the preceding volume of this series, will have no difficulty in recognizing the able and intrepid hero of "Ralph of the Roundhouse" in the manly young fellow who had just reported for duty to grim old Jack Knight.

Ralph had lived at Stanley Junction since childhood. His father had been a railroad man before him. In fact, John Fairbanks had been instrumental in bringing the Great Northern to Stanley Junction. He had in part supervised its construction.

He had died before reaping the reward of his services. However, Mrs. Fairbanks and his friends knew that he owned some twenty thousand dollars' worth of railroad stock besides his home. This stock could not be located after his death, and Ralph and his mother found themselves totally unprovided for.

They knew that in his stock deals Mr. Fairbanks had a partner. This was Gasper Farrington, a miserly but wealthy magnate of the town.

To their astonishment, this man now came forward with a mortgage on the homestead that Mrs. Fairbanks was positive had been paid off before her husband's death.

Of this, however, she could furnish no written proof. Farrington professed great sympathy for the family of his dead partner, but nevertheless he insisted on collecting the interest on the mortgage.

He seemed very anxious to get the Fairbanks family away from Stanley Junction, and even offered them a bribe to go.

This fact aroused Ralph's suspicions.

He got thinking things over. He suddenly realized what a sacrifice his noble mother was making to keep him at school.

One day he went home with a great resolve in his mind. He announced to his mother that he had decided to put aside boyish sports for hard work.

Ralph was a favorite with local railroaders. The freight yards at Acton caught fire, and Ralph was impressed into temporary service.

The lad's heroic acts won the attention and friendship of the master mechanic of the railroad. Next day Ralph found himself an employee of the Great Northern, as wiper under the foreman of the local roundhouse.

They had offered him a clerical position in the general offices down the line at Springfield, but Ralph declined. He announced his intention of beginning at the very bottom of the railroad ladder and working his way up.

How promptly and triumphantly he reached the first rung, "Ralph of the Roundhouse" has narrated.

It was a hard experience, but he soon won the reputation of turning out the cleanest, brightest locomotives in the service.

Ralph made many friends and some enemies. Among the latter was a dissolute boy named Ike Slump. This young rascal stole nearly a wagon-load of valuable brass fittings from the railroad supply shops, and not a trace of the thief or booty could be discovered by the road detectives.

Ralph had in the meantime befriended and practically adopted a poor waif, named Van Sherwin. The latter had been accidentally struck in the head by a baseball. His reason seemed gone. Ralph's tender-hearted mother cared for him as if he was an only son.

Strange to say, it was through this lone waif whom Ralph had so befriended that the young railroader was led to know a certain Farwell Gibson. This man turned out to be, like Ralph's father, a victim of the wiles of old Gasper Farrington.

Ralph and he got comparing notes. Gibson lived in a lonely stretch of woods. He was day by day doing some grading work, which enabled him to keep alive a legal charter for a cut-off railway line.

He furnished Ralph with the evidence that the mortgage on the Fairbanks home had been paid.

Incidentally, near the woodland seclusion of Farwell Gibson, Ralph ran across a wrecked wagon in a ravine. In this he discovered the metal fittings stolen from the railroad company.

Ike Slump got away, but Ralph secured the plunder. When he returned to Stanley Junction, through a lawyer he made Gasper Farrington acknowledge the mortgage on their home as invalid, much to the chagrin of the old miser.

He told Farrington, too, that he believed he had his father's twenty thousand dollars' worth of railroad bonds hidden away somewhere, and notified him that he should yet try to unravel the mystery surrounding them.

Ralph now reaped the reward of duty well done. Life grew brighter. They had a home, and Mr. Blake, the master mechanic, showed his appreciation of the recovery of the stolen plunder.

Ralph was officially notified that he was promoted to duty at the depot switch tower.

For two days he had been under the skilled tuition of old Jack Knight, learning the ropes. Now, at the noon hour of a bright, balmy autumn day, he entered upon this second grade of service in the employ of the Great Northern.

It was a pleasure to the ardent young railroader to view the panorama of rails and switches in plain view of the switch tower.

It was a fascinating novelty to study old Jack Knight at the levers. One-handed as he was for the occasion, he went through his duties like some skilled master giving an expert exhibition.

The switch levers were numbered up to twenty. In their center was a dial, a foot across. Over its surface ran an indicator, moved by an electric button one mile south, at the main signal tower at the limits of the town.

"Passenger No. 8," "Freight 10," "Express 3," "Special," "Chaser," and half a dozen other regular trains were marked on this dial.

Nearby was a telephone, also connecting with the limits tower. This was in requisition every minute to announce when trains had passed a certain switch, closed again behind them.

A large megaphone hung in readiness near an open window behind the operator, who darted from lever to lever according as he received his orders by 'phone or dial.

For two days, as Ralph had told Mort Bemis, he had been under the skilled tuition of old Jack, learning the switches.

He had gone down the tracks to the limits, foot by foot slowly, twenty times or more that morning, until he had a perfect map in his head of every rail and switch on the roadbeds.

He had familiarized himself with every lever number, and that of every train on the road. He realized that trained eye, ear, and muscle must be ever on the alert, or great loss of life and property might result at any moment.

There was a lull in active duty for the veteran towerman as the noon whistles blew. Knight set the lever for a lazy switch engine taking a siding, sent the noon accommodation on her way, closed the switches after her, and gave attention to Ralph.

"Well, Fairbanks," he said, slipping his coat over one arm and changing his cap, "think you can manage?"

"I can obey orders," answered Ralph.

"That's all you have to do. The limits gives you your cue. Never forget that they are the responsible party. If they say six, make it six, if you see that it's going to bust a train of Pullmans, depot, and all. Obey orders--that's the beginning and end. Number two is: Use your own judgment with chasers and freights when the tracks are full."

Just then the telephone bell rang. Ralph grasped the receiver.

"No. 4, express, backing in," and Ralph repeating it casually for old Jack's benefit, stepped on the long, narrow plank lining the lever platform.

"Three for the yards switch, 7 for the in main, and 4 for the express shed siding," he pronounced.

It took some muscle to pull over the big heavy levers in turn, which were not operated on the new-style compressed air system.

Knight watched him closely, nodding his head in approval as Ralph closed the switches on limits' 'phoning as the express passed certain points. As a locomotive backing three express cars passed the tower and took the sheds tracks, old Jack observed:

"You'll do. I'll drop in later. Your shift runs till 9 P.M. Then Doc Bortree will relieve you."

"All right, Mr. Knight. And thanks for all your trouble in teaching me," said Ralph.

The old towerman disappeared down the trap ladder. Ralph did not sit down. He was alone now, and it would take time and experience to dissipate the natural tension of anxiety he felt.

"It's a big responsibility for a boy," he spoke musingly. "They know their business, though," he went on, "and have confidence in me, it seems. Well, I'll make good, if strict obedience to orders is the keynote."

The ensuing hour was a great strain on Ralph's nerves. It was a critical situation, for at one o'clock it seemed as if every switch engine in the service started up simultaneously.

Three freights and one out and one in passenger complicated the situation. Ralph's eye never left the dial. His ear got trained to catching the slightest click on the telephone.

He felt as flabby as a doormat and was wet with perspiration, as he finally cleared the yards.

"Never a miss!" he panted, with a good deal of satisfaction. "It couldn't come much swifter than that at any hour of the day or night. It's genuine hard work, though, and expert work, too. Well, I've made a fair beginning."

Ralph had it quite easy for an hour now. He rested in the big cane armchair on a little elevated platform directly in front of the levers. From there he had a clear view of every foot of the yards.

Some roundhouse hands, passing by, waved him a genial hail. The depot master strolled by about three o'clock, and called up to know how Knight's hand was getting on. Just after that, Ralph fancied he recognized Mort Bemis in a group of loaferish-looking fellows on the freight tracks. A call to the levers, however, distracted his attention, and when he looked again the coterie had disappeared.

"I'll have a stirring report to make to mother to-night," reflected Ralph, with pleasurable anticipation.

A short freight had just taken the far siding. Its engineer held up two fingers to Ralph. This indicated that he wanted main two. After that his crew set the unattached switches beyond themselves.

The freight was slowing up, when Ralph saw a female form come over the bumpers of two of the moving cars. She leaped to the ground as nimbly as an expert switchman.

The fireman of the freight yelled at her and shook his fist. She tossed her head in the air and proceeded across the planked passenger roadbeds, dodging a hand-car, climbing over a stationary freight, and continuing recklessly across the railroad property where outsiders were not allowed.

She was a somewhat portly, red-faced woman of about forty. She wore a hideous poke bonnet, and carried a bulging umbrella with a heavy hooked handle.

In crossing between the cars she simply reached up with this, encircled the brake-rod with the umbrella handle, and pulled herself to the bumpers.

A flagman came rushing up to her. He pointed to the painted sign on a signal post near by, warning trespassers.

Ralph watched the determined female flare up. The flagman tried to stop her. She knocked off his cap with a sweeping blow of the umbrella, and proceeded calmly on her way with the stride of some amazon.

Ralph was wondering at her temerity and mission. She was headed straight for the switch tower.

Just then the dial clicked. "Chaser" it indicated, and down the main track came a locomotive and tender at full speed.

The 'phone gave the direction: Track 11. This was a set of rails rounding beyond the blank wall of the in freight on a sharp curve.

It took one lever to set the switch from the main track, another to open the rails inside track eleven.

On the main, forty feet farther on, stood the made-up afternoon accommodation train. On No. 12 were two dead Pullmans, ready for the night express.

The levers of in main and track eleven were less than three feet apart. Ralph grasped one with each hand, to slide the main with his right and complete the switch circuit with his left.

It was an easy task, knowing just what was wanted, and a full thirty seconds to act in.

The minute that Ralph's hands struck the levers, a thrill and then a chill--strong, overpowering, and deadly--paralyzed every nerve in his body.

Every vestige of sensation left his frame--his hands, perfectly nerveless, seemed glued to the levers.

He could not detach them, strive as he might--he could not exert a single ounce of pulling power.

With a gasp Ralph saw the chaser engine dash down the rails, a hundred, eighty, seventy, fifty feet from the main switch, tender in front, so engineer and fireman, relying on the tower service, never noticed that they were headed for a tremendous crash into the made-up accommodation.

With a sickening sense of horror Ralph strove to pull the levers. Impossible!

Something was wrong! He could not move a muscle. Like one petrified he glared down at the flying locomotive, headed straight for disaster and destruction.

CHAPTER III--A CLOSE GRAZE

Crack! Crack! Crack! Crack!

Ralph's strained hearing caught these sounds vaguely. All his attention was centered on the locomotive apparently speeding to sure disaster.

The next instant, however, he became aware that in some mysterious way these noises signalized his rescue from a terrible situation.

The lever rods his hands clasped vibrated harshly. As if by magic that glue-like suction tension on his fingers was withdrawn.

His hands still burned and tingled, but a great gasp of relief left his lips. His eyes fixed on the rushing engine, his hands now pulled the levers in order.

Not six inches from taking the in main rails, not eight seconds from reducing the accommodation to a heap of kindling wood, the "chaser" shot switch eleven, and glided smoothly to the terminus. Its serene crew never dreamed how they had grazed death by a hair's breadth.

Ralph half fell between the levers. He felt that his face must be the color of chalk. His strength was entirely spent. He still grasped the levers, hanging there for a moment like a person about to faint.

Fortunately there was no call for switch-tower service during the ensuing minute or two. Ralph tried to rally his dazed senses, to comprehend what was going on below.

For again a swishing, cracking, clattering sound rang out. This time it was followed by a curdling cry of pain.

"You'll blind me--you're tearing my hair out by the roots!" screamed a voice which Ralph instantly recognized.

It belonged to Mort Bemis. Ralph began to have a coherent suspicion as to the cause of his recent helplessness.

"I'll tear twenty-six dollars out of you, or I'll have your hide!" proclaimed strident feminine tones.

"I hain't got no money."

"You'll get it for me. What, strike me with that piece of wire! You wretch, I'll----"

There was a jangling crash, as of some heavy body thrown back against the lever cables in the lower story of the switch tower.

Then its door crashed open, and glancing through the windows Ralph saw Mort Bemis dash into view.

He sped across tracks as if for his life. He was hatless, his face was streaked with red welts. From one hand trailed a piece of insulated electric light wire.

Giving a frightened backward glance as he reached a line of freights, the ex-towerman leaped the space between two cars and disappeared from view.

From the lower story of the switch tower there now issued exclamations of rage and disgust.

Ralph started to look down the ladder trap. Just then the dial called for a switch, and duty temporarily curbed his interest and curiosity. As he set clear tracks again, a head obtruded through the trapdoor.

It was that of the resolute woman Ralph had noticed a little time past so audaciously crossing the rails and defying instructions. Her face was red and heated, her eyes flashing. Her hair was in disorder, and the poke bonnet was all awry.

"Be careful--don't fall, madam," said Ralph quickly, with inborn chivalry and politeness, springing to the trap.

He put out a hand to help her. She disdained his assistance with an impatient sniff, and cleared the ladder like an expert.

"Don't trouble yourself about me, young man," she observed crisply. "I'm able to take care of myself."

"I see you are, madam."

"I've run an ore dummy in my time, when my husband was head yardman at an iron works, and I know how to climb. See here," she demanded imperatively, fixing a keen look on the young railroader, "are you boss here?"

"Why, you might say so," answered Ralph. "That is, I am in charge here."

The woman put down her umbrella to adjust her bonnet. Ralph observed that the umbrella was in tatters and the ribs all broken and twisted. He comprehended that it was with this weapon that she had just assaulted Mort Bemis.

"If you're the boss," pursued the woman, "I'm Mrs. Davis--Mort Bemis' landlady, and I want to know what I've got to do to get twenty-six dollars thet he owes me for board and lodging for the last six weeks."

"I see," nodded Ralph--"slow pay, that fellow."

"No pay at all!" flashed out the woman wrathfully. "He came to me month before last with a great story of promotion, big salary, and all his back funds tied up in a savings bank at Springfield. Last pay day he claimed someone robbed him. This pay day he dropped from the garret window, leaving an old empty trunk. I got on his trail to-day, and I want to garnishee his wages. How do I go about it?"

"I don't know the process," said Ralph, "never having had any experience in that class of business, but I should say garnisheeing in this case would simply be sending good money after bad."

"How?" demanded Mrs. Davis sharply.

"Bemis has very likely drawn every cent the company owes him."

"But his pay is running on."

"Not now, madam. He was discharged two days ago."

"W-what!" voiced Mrs. Davis, in dismay. "And won't he be taken back?"

"From what I hear--hardly," said Ralph.

The woman's strong, weather-beaten features relaxed. All her impetuosity seemed to die out with her hope. Ralph felt sorry for her. She was brusque and harsh of manner, masculine in her ways, but the womanly helplessness now exhibited was pathetic.

She tottered back to the armchair, every vestige of willfulness and force gone. Apparently this odd creature never did things by halves. She sunk down in the chair, and began to cry as if her heart would break. Ralph was called back to the levers and had no time to console her. He watched her pityingly, however. Between her sobbings and incoherent lamentations he pretty clearly made out the history of her present woes.

Mort Bemis had, it seemed, shown himself a "dead beat of the first water." Mrs. Davis had recently come to Stanley Junction, and had rented an old house near a factory owned by Gasper Farrington.

Bemis had applied for board and lodging. With what he promised to pay, and with what she could make off an orchard, vegetable patch, and some poultry, this would give Mrs. Davis a fair living.

"And he never paid me a cent," she sobbed out. "Last Saturday my last cent went for flour. Yesterday I used up the last bread in the house. I haven't eaten a morsel this blessed day. The man who owns the house threatens to turn me out if I don't pay the six dollars rent by six o'clock to-night, and all for that rascally, thieving Bemis! A full-grown man, and robbing and cheating a poor lone widow like me!"

Ralph glanced up and down the rails. Then he glided over to the clothes closet at the end of the tower room and secured his dinner pail.

"And what was the scoundrel up to below, when I discovered him just now, I'd like to know?" went on Mrs. Davis. "Some dirty mischief, I'll be bound. He had a wire fixed around a bigger one, and was holding the scraped copper ends against the lever cables till they sparked out little flashes of fire. Say, can't he be arrested for swindling me? The reprobate deserves to suffer."

Ralph gave a little start of comprehension just there. The woman's last recital had cleared up the mystery of his recent sudden helplessness.

There was no doubt whatever in his mind but that the revengeful Mort Bemis had started in to "fix" him, as he had threatened earlier in the day. His knowledge of the details and environment of the switch tower had enabled him to work out a well-devised scheme.

Ralph knew that Bemis was determined to undermine and discredit him at any cost.

He theorized that in some way Bemis had connected the current from the wires that looped up from the road boxes into the tower. He had the practiced eye to know what levers Ralph would use. Bemis had thrown on the current, magnetizing the new leverman at just the critical moment.

But for the providential intervention of Mrs. Davis a destructive collision would have occurred, Ralph would have been disgraced, and there would have been a vacancy at the switch tower.

"The villain!" breathed Ralph, all afire with indignation, and then his glance softened as he turned to the woman seated in the armchair. Her grief had spent itself, but she sat with her chin sunk in one hand, moping dejectedly.

There was a short bench near one of the windows. Ralph pulled this up in front of the armchair. He opened his lunch pail and spread out a napkin on the bench. Then on this he placed two home-made sandwiches, a piece of apple pie, and a square of the raisin cake that had made his mother famous as a first-class cook.

All this Ralph did so quickly that Mrs. Davis, absorbed in her gloomy thoughts, did not notice him. He touched her arm gently.

"I want you to sample my mother's cooking, Mrs. Davis," he said, with a pleasant smile. "You will feel better if you eat a little, and I want to tell you something."

"Well, well! did you ever?" exclaimed Mrs. Davis, noting now the sudden transformation of the bench into a lunch table. "Why, boy," she continued, with a keen stare at Ralph, "I can't take your victuals away from you."

"But you must eat," insisted Ralph. "I had a hearty dinner, and have a warm supper waiting for me soon after dark. I brought the dinner pail along just as a matter of form in a way, see."

"Yes, I do see," answered his visitor, with a gulp, and new tears in her eyes--"I see you are a good boy, and a blessing to a good mother, I'll warrant."

"You are right about the good mother, Mrs. Davis," said Ralph, "and I want you to go and see her, to judge for yourself."

Mrs. Davis munched a sandwich. She looked flustered at Ralph's suggestion.

"I'm hardly in a position to make calls--I'm dreadfully poor and humble just now," she said in a broken tone.

"Well," repeated Ralph decisively, "you must call on my mother this afternoon. You see, Mrs. Davis, that rent of yours has got to be paid by six o'clock, hasn't it?"

"The landlord said so."

"I have only a dollar or so in my pocket here," continued Ralph, "but my mother has some of my savings up at the house. I want to let you have ten dollars. I will write a note to my mother, and she will let you have it."

Mrs. Davis let the sandwich she was eating fall nervelessly to the napkin.

"What--what are you saying!" she spoke, staring in perplexity at Ralph.

"Why, you must pay your rent, you know," said Ralph, "and you need a little surplus till you get on your feet again. There may be some way of shaming or forcing Mort Bemis into paying that twenty-six dollars. If there is, I will discover it for you."

"But--but you don't know me. I'm a stranger to you. I couldn't take money from a boy like you, working hard as you must, probably for little enough wages," vociferated Mrs. Davis, strangely stirred up by the generous proffer. "I might take a loan from somebody able to spare the money, for I can write to a sister at a distance and get a trifle, and pay it back again, but not from you. No--no, thank you just the same--just the same," and the woman broke down completely, crying again.

Ralph sprang to the levers at a new switch call. Then he resumed his argument.

"Mrs. Davis, you shall take the ten dollars, and you shall have twenty if you need it, and that is an end to it. First: because you are in distress and I have it to spare. Next: because I owe you a debt money cannot pay."

"Nonsense, boy," spoke Mrs. Davis dubiously.

"It's true. You don't happen to know it, but you have saved my position and my character this afternoon. You have probably saved the railroad company great loss of property, if not of life itself. I should be a grateful boy to you, Mrs. Davis. Let me tell you why."

Ralph did tell her. He recited the story of the last hour at the levers. Before she could make a comment at its termination, he had written and thrust into her hand a note addressed to his mother.

"I'll take the ten dollars," said Mrs. Davis, in a subdued tone, after he had directed her to his home, "but only as a loan. You shall have it back quick as I can get word from my sister."

"As you like about that," answered Ralph. "I hope you will make a friend of my mother," he added. "She has had her troubles, and you would be the happier for asking her counsel."

"Yes, I've had a heap of troubles, boy," sighed Mrs. Davis. "Oh, dear! I may be a little good in the world, after all. And," with a wistful look at Ralph, "it's hopeful to think all boys aren't like bad Mort Bemis. And here I'm borrowing money from you, and don't even know your name."

She groped in a pocket and drew forth a worn memorandum book and a pencil. Then, opening the book at a blank page, she looked up inquiringly at Ralph.

"Fairbanks," dictated Ralph.

Mrs. Davis had placed the pencil point on the blank page, ready to write. As Ralph spoke her hand seemed swayed by a great shock.

The pencil and book were nervelessly dropped to the floor. She turned a colorless face towards Ralph, and, shrinking back in the creaking armchair, stared at him so strangely and fixedly that he was unable to understand her sudden emotion.

CHAPTER IV--A MYSTERY

Ralph looked at his switch-tower visitor in great surprise.

"Why, Mrs. Davis," he asked, "what is the matter?"

"N--nothing," she stammered, trying to control herself, but her features were working strangely. "So your name is Fairbanks?"

"Yes, Mrs. Davis."

"Not John Fairbanks--how simple I am, though, of course not. He was an old man. Are you his son, then?"

"Yes," answered Ralph, his curiosity excited. "My name is Ralph. I am John Fairbanks' son. He is dead, you know. Were you acquainted with him?"

"Not acquainted exactly," replied the woman, in a certain repressed way. "I have heard of him, you see."

"Oh, you mean since you came to Stanley Junction?"

"No, no, a long way from here, and a long time ago. Where I used to live. I heard he was dead, and I heard you and your mother was dead, too. I did not dream that any of the Fairbanks were here now."

"Why, you amaze me!" cried Ralph. "Who could have told you that?"

"A certain man. He told a falsehood, didn't he? I might have known it. I see now--yes, I begin to see how things are."

She said this in a musing tone, as if half-forgetting that she had an auditor. Ralph was more than interested. He was startled. He knew enough of human nature to guess that Mrs. Davis was concealing something from him.

She arose quite flustered, and began to arrange her bonnet. She evaded Ralph's eye, and appeared anxious to get away. Ralph determined to press some further inquiries. Before he could begin, she made the remark:

"You are a good boy, Ralph Fairbanks, and I shan't forget you. I will take the loan you offer me, but it will be promptly paid back, very soon. Boy," she continued, with a good deal of animation, as if suddenly stirred by some impulsive thought, "you will get a blessing for being good to a poor lone widow, see if you don't."

"I seem to be getting blessings all the time," said Ralph lightly, but reverently. "I guess life is full of them, if you do right and put yourself in the way of them. Is there some special blessing you are thinking of, Mrs. Davis?" he inquired, saying the words because the woman had used a certain significant, mysterious tone in her last statement. This made him believe she could be clearer and say a deal more, if she chose to do so.

"Yes, there is," replied Mrs. Davis, almost excitedly. "You mustn't question me, though, boy--not just now, anyway. You have given me a lot to think of. I may tell you something very important later on--I may tell your mother to-day. Good-by."

As she approached the trap in the floor, Ralph got a call for a switch. He was reluctant to let his visitor depart. Her vague revelations disturbed him. When he had attended to the levers, he turned again to Mrs. Davis. In doing so he chanced to glance down at the near tracks, and fixedly regarded two approaching figures.

"Hello," he spoke irrepressibly, aloud. "Coming here--the master mechanic and Gasper Farrington."

"What's that--who?" cried Mrs. Davis, almost in a shout.

Ralph looked at her in new amazement. As she had caught the last name he had spoken, she stood erect in a strained, tense way, seeming to be frightened.

The two men Ralph had indicated now crossed the tracks and entered the switch tower below. Their voices could be heard distinctly.

"We have a switch plan upstairs in the tower, Mr. Farrington," sounded the clear, incisive tones of Mr. Blake, the master mechanic of the Great Northern.

"All right," answered his companion, and the accents of his voice seemed to be familiar to Mrs. Davis. She looked almost terrified. She glanced wildly around the tower room.

"Hide me!" she gasped appealingly to Ralph.

"Why, what for?" he inquired.

"It's Gasper Farrington, isn't it, just as you said? And he is coming up here!"

"It seems that he is, Mrs. Davis," responded Ralph.

"I don't want to meet him. I don't want him to see me--not yet," went on the woman rapidly.

"Are you afraid of Gasper Farrington, Mrs. Davis?" asked Ralph pointedly.

But she did not answer him. She glided to the coat closet at the end of the room, as if seeking a hiding-place. As she pulled its door open, she noticed that it was too shallow to admit a human form.

The dial again called Ralph. By the time he had attended to the levers, he noticed that Mrs. Davis had produced a thick heavy veil and was concealing her face under it. She stood fidgeting nervously at a window at the far end of the room, her back turned to the trapdoor, as if to escape direct attention.

The master mechanic came into view. Then he helped his companion into the room.

Ralph caught his breath quickly and his lips compressed a trifle, as he recognized Gasper Farrington.

His advent was a certain new cause of some inquietude to the young leverman. An old-time enemy, and a bitter and crafty one, Ralph knew he could never expect any good from the miserly old magnate of Stanley Junction.

Farrington's wealth and position gave him a certain influence and power that had been repeatedly used to crush those he did not like. He disliked the Fairbanks family for more reasons than one, and he had tried to crush Ralph more than once. In these efforts, however, he had failed. Ralph had come off the victor because he was in the right, which always prevails, sooner or later.

In their last encounter, Ralph had forced the scheming Farrington to release the fraudulent mortgage he held on the Fairbanks cottage. He had bargained to keep the humiliating details of Farrington's swindling operations secret as long as the defeated magnate let them alone. He did not think that Farrington would now risk public exposure by attempting any further tricky measures of gain or revenge. Still, Ralph disliked coming in contact with the man, who would willingly do him an injury and gloat over his downfall.

He was glad that Farrington did not notice him. The attention of the magnate was at once directed to a blue-print plan nailed between two windows.

"There is the switch plan of the yards, Mr. Farrington," said the master mechanic, indicating the sheet of paper in question.

Mr. Blake nodded to Ralph. Then he looked inquiringly at Mrs. Davis.

"A lady who was looking for Mort Bemis," explained Ralph. "He owes her some money, it seems."

"He owes about everybody he can work," said the master mechanic brusquely, and crossed the room after Farrington.

Mrs. Davis quickly went to the trap. She kept her eye on Gasper Farrington until safely down on the ladder, placed her finger on her lips in significant adieu to Ralph, and then disappeared.

The latter stood at the levers, his back turned purposely on the newcomers into the switch tower.

There was no need of his having an encounter with Farrington, if it could be avoided. Ralph attended to his duties strictly. However, he could not help overhearing what the two men at the side of the room were saying.

Ralph soon divined the nature of Farrington's visit to the switch tower. The magnate owned a factory building about half a mile from the railroad. It had stood vacant and abandoned for some time, as Ralph knew. Now, it seemed, a manufacturer had agreed to lease it for a term of years, provided he could have direct railroad transportation facilities put in.

This point the two men at the switch plan were now discussing. Farrington was following the finger of the master mechanic, as it moved along over the traceries of white and red ink that crisscrossed the blue print.

"Here is where you start your spur," Mr. Blake was explaining. "We can put you in a single track, you to bear half the expense."

"You mean one-third," interrupted the bargaining old schemer.

"I mean just what I said," observed the master mechanic grimly. "It is a long reach for a siding, you have no right of way, and we are supplying it, although we will have to run a pretty steep grade down the ravine, for that is the only land we own in your direction. We have right of way to within three hundred feet of your factory. As to the strip that intervenes----"

"Oh, there's nothing there but an old shanty on leasehold," answered Farrington.

"Can you get permission to cross it?" asked Blake.

"He! he!" chuckled Farrington; "can I get it? I'll take it!"

"Well, that is your own matter," spoke Blake. "All we want is a bond guarantee for five years, that you will run enough freight over the spur to equal a ten per cent. annual investment."

"Isn't my word good enough for that?" demanded Farrington arrogantly.

"The Great Northern takes no man's word where a contract is concerned," was the definite answer.

"All right, close the matter up as soon as you like," said Farrington. "Here's where you control the switches, eh?" he continued, leaving the plat and taking a curious glance about the tower.

"Yes."

"I should say it took a clear head and lots of experience to avoid mistakes."

"It does, and lots of muscle, too--eh, Fairbanks?" spoke the master mechanic.

Ralph nodded. He aimed to escape recognition at the hands of Farrington, who, in another minute, would have left the place. He knew, however, that he was discovered, as the magnate uttered a short, sharp grunt.

CHAPTER V--THE STOWAWAY

"What's that?" called out Gasper Farrington, hobbling up to the levers and staring at Ralph. "Look here, Mr. Blake," he pursued, his brows drawn in a mean, savage scowl. "You don't mean to tell me this boy has anything to do with your switching?"

"He has everything to do with it," announced the master mechanic, looking as if he was disposed to resent the manner and words of the client he did not like any too well himself.

"Well, then, it won't do!" snarled Farrington, getting excited. "I want trustworthy service, I do. I don't propose to run the risk of damage and loss with a road that hires kids for its most important work."

Mr. Blake's lips drew tightly together. Then he remarked:

"Mr. Farrington, the Great Northern knows its business distinctly, we are responsible for any damage caused by the negligence or inability of our employees. In this instance you may quiet your needless fears. Mr. Fairbanks thoroughly understands his business, and I personally recommended him to his present position on account of the cleanest record and best practical ability of any junior employee of the company."

"H'm. Ha! That so?" mumbled Farrington, taken a good deal aback by Blake's definite expressions of approval, while Ralph felt his heart beat with pleasure, and blushed hotly. "All right. I suppose you think you know your business. Only--he was a barefooted urchin six months ago."

"He has earned a good many pairs of shoes since then," observed Blake crisply.

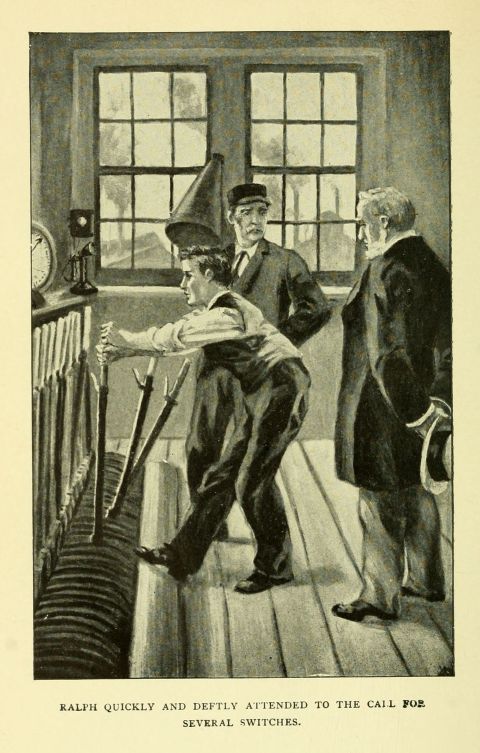

Ralph said not a word. A spell of silence ensued. Farrington stood like some baffled hyena held back from its prey. Ralph quickly and deftly attended to the call for several switches, with a precision and system that even interested the master mechanic.

"It strikes me he'll do," spoke Blake, and Ralph looked grateful as the master mechanic plainly evidenced a pride in the demonstrated ability of his young protégé.

All this roused the vengeful, malignant Farrington to the verge of impotent fury.

"Ah," he growled, "favor cheap help, I suppose? All right. Though be sure to make it your business if any damage comes, that's all. That boy owes me a grudge, and if I know anything of human nature, there will be a wreck on the factory spur before it's been running long."

Ralph felt his fingers tingle. He decided that he had a right to speak now. He faced about squarely. The mean-eyed magnate quailed at the honest indignation of his glance.

"Mr. Farrington," said Ralph, "have I ever sought to do you an injury?"

"Yes--no--perhaps not," stammered Farrington, "but you would like to."

"Why?" demanded Ralph definitely.

"Because--because--oh, I know you. I know the whole brood. You smashed a window in my factory, once."

"Accidentally. And paid for it. Is that true?"

Farrington squirmed. He wanted to back out. He found that he could not domineer in the present instance. More than that, he realized that he dared not. The master mechanic, with a grim smile on his lip, helped him out of the dilemma.

"Come, Mr. Farrington," he said, smartly clicking his watch and helping him through the trap. "We will miss the superintendent, and you say you want to close up this business to-day. Careful, take it a rung at a time--you skunk!" he concluded in an undertone to Ralph, giving him a significant look, and meaning the words for Ralph's ear only.

Ralph felt as if the air was cleared of some violent poison at the departure of this miserable apology of a man.

"Faugh! I won't think of him," he soliloquized. "What possible happiness in life can such people have? I wonder which is the worst: Mort Bemis, poor and mean, or Gasper Farrington, rich and mean. Which carries out what mother has often said: 'Money is not everything.'"

Ralph dismissed his enemies from his mind, whistling cheerily at his tasks. He thought a good deal about Mrs. Davis. He was anxious to get through work and hurry home, to learn if she had called on his mother, and if she had imparted to Mrs. Fairbanks any explanation of her strange acquaintance with his dead father, and of her still more strange fear of Gasper Farrington.

From five until seven o'clock the tracks were kept pretty full. Ralph had a busy time of it. He got through without a delay or a mix-up, however. Jack Knight came up the ladder about eight o'clock.

He looked pleased at the collected, business-like way that Ralph handled things. He finally remarked:

"Met Blake a bit back, Fairbanks."

"The master mechanic--yes," nodded Ralph.

"Keep it under your hat, now," continued Knight significantly. "Blake was riled. He said he'd give half a month's salary to wallop one man in Stanley Junction, if it wasn't business policy to keep down personal feelings for the good of the service."

"Who was the man, Mr. Knight?"

"He didn't say, but no friend of yours, it seems. The gist of it is, that this man--I'd like a crack at him myself--offered Blake two hundred dollars to get you shifted onto some other section."

"I seem to come high," smiled Ralph, although he experienced a faint uneasiness at mind, as he clearly comprehended that Gasper Farrington was up to some of his old underhanded tricks.

"Well, Blake politely turned down the offer. He said to me, though, that if any treachery or influence got you the jacket in this position, if he had to fire every other man along the line, he'd find a place for you in the train dispatcher's office at double pay."

"He is a good friend," said Ralph, with emotion--"and you, too, for giving me the warning, Mr. Knight. Knowing what I do, though, I think I can take care of myself. I do not believe the man you refer to will succeed in disturbing me here."

"He won't, if I can help it," muttered old Jack doughtily.

"Hello, there!" hailed Doc Bortree, the nightshift man, intruding his bulky form and big, jolly face through the trap.

Bortree was a general favorite. He carried an atmosphere of good nature always along with him.

"Well, kid," he hailed. "Busted anything to-day?"

"Not yet," answered Ralph gayly.

They sent him home forthwith. Ralph felt very happy as he descended the ladder from his first real day's service at the switch tower.

His work had gone smoothly, and he loved it. A spice of new interest had been injected into his personal affairs that day, and his mental conjectures were not unpleasant ones.

"I wonder if Mrs. Davis saw mother?" he mused, as he crossed the tracks, homeward bound. "Hello, a stowaway!"

Ralph halted, just passing a line of delayed freights. A great thumping was going on at the side door of the end car.

"Someone in there, sure," soliloquized Ralph.

"A tramp, I suppose. Stowed in at some point, and side-tracked here this morning. Out with you, whoever you are!" ordered Ralph, unbolting and sliding back the door.

In the dim light of a distant arc lamp Ralph made out a forlorn figure. The stowaway was shabby and peaked-looking, holding in one hand a piece of wood with which he had been hammering for release.

His face was so grimed that Ralph took him for a negro at first. Always kind-hearted, the young leverman had not hesitated to give the stowaway prompt liberty, and it was in his mind to help him farther if necessary.

The stowaway glanced all about the yards as if fearing the gauntlet of cuffs and kicks often in vogue for his class. Then, rubbing his eyes to clear the glare of sudden light, he looked sharply at Ralph.

"Hello," he exclaimed, shooting back out of view. "It's Fairbanks!"

"What's that?" cried Ralph, catching the name in wonderment. "Here, who are you? Do you know me?"

Suddenly as the figure had vanished within the dark car, it now reappeared. With a spring the stowaway cleared the doorway of the car, landing on the cinders beside Ralph.

"Take that!" he hissed, savagely whirling the club above his head.

Ralph dodged. Mystified and unprepared, however, his usual agility was at fault.

A heavy blow landed on the side of his head, and Ralph fell flat.

CHAPTER VI--MRS. FAIRBANKS' VISITOR

It seemed to Ralph that his eyes closed tight shut for half a minute, and then came open as wide as ever.

He did not believe he lost consciousness for more than thirty seconds. That, however, was time enough for his mysterious assailant to make himself scarce.

Ralph got to his feet, quite shaken. His hand went to the side of his head involuntarily. His left cheek was scraped and full of splinters, though not bleeding. A big lump was rising in front of one ear.

On the ground lay the club that had dealt Ralph the blow. He moved it with his foot to find it heavy, as if made of hard wood.

"Why, the fellow might have killed me had he struck a little harder," said Ralph seriously. "Who was he? It must be that he knows me, for he spoke my name."

There was a hydrant in the center of a platform space near by. Ralph went over to this and turned on the water and sopped his handkerchief, applying it to the lump on his head.

"Was it Mort Bemis?" his mind ran on. "No, I am sure it was not. Bemis is stubby and broad, this fellow was tall and slim. Looked like a half-starved rat. Who could it be?"

In a minute or two Ralph went back to the car that had proven for him a kind of Pandora's box.

He lifted himself through the open doorway and flashed some matches.

The car was bare. It smelted of tobacco smoke, and there was a litter of cigarette stubs in one corner. The other closed door was back-sheathed with smooth boards. Under these Ralph discovered some fresh whittlings, or splinters. He inspected door and floor more closely.

"Ah, I see," he observed: "the stowaway has been killing time by cutting his name on the pillar of fame."

The door surface bore a record of various jackknife experts. Idle hands, belonging to all kinds of ride-stealers, had from time to time cut their initials on the smooth boards.

There were some pencilings, too--all kinds of doggerel slang and initials. Thus: "Turnpike Tim on his fift' trip sout'." "Mugsey, the Terror," and the warning line: "Bad road for tramps, twice for flipping trains."

The last stowaway, as evidenced by two letters cut into the board, had sought to rival his predecessors. The newly indented initials were nearly eight inches long, and formed an I and an S.

"'I.S.,'" read Ralph. "The solution is easy. It was Ike Slump. Those are his initials, and, come to recall my fierce assailant, he fits Ike's size exactly. That mean attack, too, would be characteristic of Slump. He was afraid of me. He needs to be. There is a standing reward of twenty-five dollars from the railroad for his arrest. I don't want the reward, but I don't propose to have him come back to his old haunts and associates to bother me."

Ralph walked home slowly. The blow he had received caused him some pain. The addition of the malignant Ike Slump to the list of his active enemies troubled him. Ralph knew what it was to fight a mean, underhanded foe. The roster so far included not only Slump, but Bemis and Gasper Farrington.

"It's my duty to notify the railroad company that Slump is again on hand," declared Ralph. "That will dispose of him. As to Bemis, I shall seek him out and give him a warning. If he troubles me any further I will have him arrested for his malicious mischief of to-day. It would be a pretty serious charge--endangering the railroad property. Gasper Farrington will not do anything openly to harm me. He dare not. But he will work against me in the dark, if he sees the chance to do it. Well, I shall watch his movements mighty closely."

Ralph spurred up as he came within the lights of home. The lamp burning brightly in the front room of the neat little cottage was always a cheering beacon to him, for he knew it had been placed by loving hands.

Mrs. Fairbanks, the tender, thoughtful mother, made that home a peaceful paradise for her only son. She greeted Ralph at the door with a welcome that made him forget instantly all of the cares and troubles of the day in entering the sheltering of a rare haven of rest and contentment.

Ralph took a good wash at the kitchen sink, put on a clean collar and tie and a light housecoat. Then he sat down to a table steaming with appetizing food.

"Why, Ralph," instantly spoke Mrs. Fairbanks, "you have been hurt!"

Ralph carelessly moved his hand over the lump on his head.

"Nothing serious, mother," he declared with a reassuring smile. "A fellow generally gets some initiation bumps on his first day in a new job on the railroad."

Mrs. Fairbanks was scarcely satisfied with this off-hand explanation, but Ralph at once shifted the conversation into other channels. He made up his mind he would not worry his mother with the story of his encounter with Ike Slump, at least for the present.

"By the way," he said, as he stowed away a hearty meal, "did you have a visitor to-day, mother?"

"Why, yes," answered Mrs. Fairbanks. "A lady--Mrs. Davis."

"I am glad she came," said Ralph. "She took the ten dollars I wrote you about?"

"Rather reluctantly. She is a strange woman," went on Mrs. Fairbanks thoughtfully; "I could not quite make her out. She acted quite flighty at times, but I believe she is honest, and very earnest in her gratitude and good intentions towards you."

"Why, yes," answered Ralph, with a suggestive smile. "She promised me a blessing. Have you any idea of what she was driving at?" he questioned, scanning his mother's face closely, for he observed that it bore a vague, disturbed expression.

"I think I have, Ralph. It appears that she knew--or at least knew about--your father, some years ago."

"She told me that."

"And she knows Gasper Farrington. She asked me a queer question, Ralph."

"What was it, mother?"

"If father did not once own twenty thousand dollars in railroad bonds, and if we had ever got them."

Ralph stopped eating for a moment.

"She said that, did she?" he murmured. "Mother, wouldn't it be strange if she knew something about those bonds?"

"She does."

"How do you know?"

"Because she admitted it. Mrs. Davis was very much agitated. She seemed on the point constantly of telling me something, and then she would mutter to herself and apparently change her mind. When she went away she looked at me very strangely and said: 'Mrs. Fairbanks, when I get the money from my sister to pay your son back the ten dollars he has so kindly loaned me, I am going to tell him a little story about those twenty thousand dollars bonds that may interest him.'"

The bonds formed the topic of conversation for mother and son for nearly an hour after that. They could only surmise and anticipate, but both were very much stirred up.

"I tell you, mother," said Ralph emphatically, "that woman knows something of importance to us about those bonds. You and I and others have never doubted that Gasper Farrington stole them from father. I have never given up the idea that some day I would reach the truth, and force Farrington to disgorge, just as we made him release the fraudulent mortgage. I really believe things are going to turn so as get us our full rights."

"We will hope so, Ralph," said the widow, with a dubious sigh. "And now tell me all about your first day in the switch tower."

Ralph went to bed about eleven o'clock. He had a good sleep until eight in the morning, devoted an hour or two to tidying up the yard and assisting his mother in various ways, and at noon started for work again.

Old Jack Knight was on duty, and spelled Ralph at the levers until about four o'clock. No unusual incident disturbed the usual routine until an hour later.

In starting to give a switch engine the siding, Ralph found the lever would not budge. The locomotive engineer discovered the unset switch in time to stop. Ralph megaphoned to hold stationary till he investigated, and ran down the ladder.

He found the lever cables chained to a wall bracket. Of course here was some more spite work. He removed the obstruction, hurried upstairs, switched the delayed engine, and kept an eye out for the watchman who covered that part of the yards.

When he finally appeared in view, Ralph hailed him and asked him to come inside the tower.

"Mr. Brady," he explained, "I wish you would keep a close eye on the lower story here for a day or two."

"Why, what's wrong?" inquired the watchman.

"Well, someone is up to dirty work," replied Ralph. "They tried to put two levers out of commission yesterday, and just now I found another lever chained up."

The watchman looked startled, and whistled under his breath.

"That's pretty serious," he remarked.

"It is," responded Ralph. "I wish you would keep a watch on strangers."

"And discharged employees?" interrogated the watchman, with a shrewd nod. "I think I know what's up, and who is up to it."

Ralph felt certain that Mort Bemis was back of the last attempt to cripple his usefulness. He did not, however, believe that Bemis himself had chained the lever, for he had kept a pretty close watch of the yards all afternoon, and had seen nothing of the discharged leverman. Ralph theorized that Bemis had put some associate up to the trick. It was an easy matter for any passer-by to step into the lower story of the switch tower without being seen from above. Ralph made up his mind he would seek out Bemis. When he was relieved after dark he did not go home. He had made some inquiries of Knight as to the present whereabouts and haunts of Mort Bemis, and Ralph thought he knew where to look for the fellow.

CHAPTER VII--"YOUNG SLAVIN"

Railroad Street to the right of Stanley Junction was a busy, respectable thoroughfare. There were a hotel, some restaurants, a store or two, and beyond these some old residences.

To the left, however, the street retrograded into second-hand stores, junk-shops, and the like, cheap eating places and boarding-houses, with a mixture of saloons.

The lower class of railroad employees and the scum of the Junction usually infested these places. At a restaurant called "The Signal" Ralph, from what he learned that day, felt he was pretty sure to get some trace of Mort Bemis.

He went by the place slowly once or twice, but could not discover Bemis in the crowded front room.

Then he paced down the alley at the side of the building. Several lower-story apartments showed lighted up. He approached the open window of one of these.

As he did so, he noticed that directly under it lay some person asleep, rolled up in horse-blankets. Ralph nearly stumbled over this individual.

He glanced into the room beyond the window. It held a table, at which was seated the object of his search.

Mort Bemis was idly pawing over a greasy deck of playing cards. He seemed to be awaiting the arrival of congenial company. Tilted back in a chair against the wall near by, a skullcap pulled down over his eyes and seemingly asleep, was a person Ralph did not recognize.

Ralph now stepped cautiously over the sleeper at his feet so as not to disturb him, and went around to the front of the restaurant.

It was run by a man named Prince, who at one time had conducted eating camps for railroad construction crews. He kept lodgers upstairs, and derived a good deal of revenue by letting out the rear rooms of the lower floor to card-players.

Ralph entered the restaurant and passed through a curtained doorway at one side. Prince, at the cashier's desk, gave him a keen look, but took him for some new recruit to the crowd who infested the rear rooms.

A narrow passageway led the length of the rear addition. Ralph turned the knob of the second door he reached. He found he had correctly located the apartment he had viewed from the alley.

Mort Bemis looked up as Ralph closed the door behind him. He started and stared. Ralph came around to the table, sank into the chair directly opposite Bemis, and looked him squarely in the face.

"What are you doing here?" demanded Bemis a surly, suspicious expression crossing his features.

"I came particularly to see you," answered Ralph calmly. "Can I have your attention for a minute or two?"

"Just two of them," growled Bemis.

Ralph did not scare at the bullying, significant manner of the discharged leverman.

"It's just this," he said bluntly: "you visited the switch tower yesterday and came very nearly causing a bad wreck."

"Who told you so?" demanded Bemis.

"Oh, there are plenty of witnesses, your former landlady, for one. Another low-down trick was attempted this afternoon, instigated, I believe, by you. Now, Mr. Bemis, this has come to a dead-open-and-shut conclusion."

"Has it? How?" sneered Mort.

"I have legitimately succeeded to your position, and I intend to hold it. You seem resolved to discredit and disgrace me. It won't work. If you make one more break in my direction, I shall go to the superintendent of the Great Northern, make a formal complaint of malicious mischief, and then enter a regular complaint with the police."

Mort Bemis did not reply. His bluff was gone, for he knew that Ralph meant every word that he said.

"There's another thing," pursued Ralph: "you owe a poor widow money that she needs, and needs badly. If you have any sense of shame or honor in your nature, you will find honest work and pay her."

"I don't want none of your advice!" flared out Bemis. "You've said your say! Then get out. I'll keep hands off because I don't fancy being locked up, but," he added with a malicious grin, "I can't hold back my friends from doing what they like."

"You have had your warning," said Ralph quietly, rising to his feet. "I've given you your chance. Leave my affairs alone, if you are wise."

Ralph started for the door. Suddenly his way was blocked. The person he had supposed to be asleep, tilted back against the wall in a chair, had roused up with marvelous quickness.

As this individual threw back his skullcap, he revealed the coarse, bloated face of a boy about two years Ralph's senior. He was a powerfully-built fellow. Ralph remembered having seen him once in the hands of the police after a raid on a chicken fight at the fair grounds.

"Easy," spoke this person, springing between Ralph and the door, and doubling up his fists pugilist-fashion. "This gent is my friend, and you've insulted him."

"I think not," said Ralph calmly.

"Do all your thinking quick, then," advised the other, "for I want satisfaction."

The speaker drove at Ralph with one hand. It was a sledge-hammer blow. Ralph whirled half-way across the room.

His antagonist followed him up quickly. His back now to the window, he put up his fists anew.

"I wanted some training," he chuckled. "Come up to your punishment. Do you know who I am?"

"I do not, and don't care," answered Ralph quickly, nettled out of his ordinary composure by a blow that had nearly knocked the breath out of his body.

"Then you can't read the newspapers. I'm Young Slavin, the juvenile Hercules, light-weight champeen. Come, wade in; I give you one chanct."

"I have no quarrel with you," remarked Ralph. "Stand aside. I wish to leave this room."

"Ho! ho! When you do, it will be on a shutter."

"And I shall not let you pound me. I warn you to mind your own business."

"Time!" roared the pugilist gloatingly.

Ralph took in the situation in all its bearings. He realized that he confronted a young giant. To oppose his prodigious muscular strength in even battle would be to be hammered to a jelly.

The occasion called for action, however. Ralph reflected for a bare minute, and then he "waded in."

With a rush he made a slanting dive for the brutal bully, aiming squarely for his feet.

Exercising all the muscle of which he was capable, Ralph grasped his antagonist's ankles, took him off his guard, gave him a sudden trip, and sent him toppling backwards.

With a yell of consternation and pain Young Slavin went crashing through the window sash.

CHAPTER VIII--A BAD LOT

Mort Bemis gave an astonished gasp as he saw his crony disappear like magic through the window sash.

His respect for the nerve and prowess of his successor at the switch tower was immensely increased. He spoke not a word, being stupefied and cowed.

Ralph started to leave the room, unmolested now. A sudden outcry checked him. He proceeded to its source--the open window.

Below it on the ground a stirring scene was in progress. It seemed that his masterly fling of Young Slavin had landed that juvenile Hercules directly on top of the individual Ralph had noticed lying asleep under the window, swathed in horse-blankets.

Aroused from dense slumber by a terrific shock, this person had struggled to his feet.

"Well, well," said Ralph, his eyes opening wide as he recognized the disturbed sleeper; "Ike Slump again."

Ralph at once knew the gaunt, desperate-looking fellow, who had jumped from the delayed freight car and knocked him down the previous evening.

The stowaway's face was no longer grimed, and Ralph had a clear view now of its natural lineaments. It was Ike Slump, peaked and wretched-looking. His appearance evidenced that his stolen junk operations and his later fugitive role had not led him into any pleasant path of flowers.

It seemed that Slump, skulking anywhere for hiding and repose like a hunted rat, had utilized the horse-blankets as a bed.

It seemed, too, that he was in constant dread of discovery and arrest. He must have slept with a missile or a weapon always handy, for his fingers now clutched a brick.

Suddenly disturbed, his nervous fears aroused, at sea as to the cause of the shock as Slavin landed on him, Ike had come erect, grabbing the brick instanter.

He was all entangled in his bed coverings, but he maintained a staggering footing. He was reaching out for his disturber to beat him off with the brick.

"You've broken my nose," he yelled; "take that--take that!"

"Murder!" howled Young Slavin.

He did not use his doughty fists, for he could not. In blind rage and terror Ike was striking out with the brick.

He delivered several blows on Slavin's head and face that made Ralph shudder.

A final one sent the young pugilist reeling back against the clapboards of the house. He was blinded with blood and pain, and shouted for help in sniveling terror.

Slump kicked his feet free of the entangling horse-blankets, and darted away towards the railroad tracks.

Ralph turned in disgust from the scene. He faced Bemis, who, his curiosity awakened by the tumult, had come to the window.

"You are training with a nice crowd, Mr. Bemis," observed Ralph. "Better switch off and get back to the main tracks."

"Lots of show for me, isn't there?" growled Mort sullenly.

"Get a roundhouse clearance of clean flues and headlights, and try it," answered Ralph.

The allusions were technical ones that Bemis fully understood. But he only blinked his bleared eyes, and more savagely gritted his teeth on the cigarette he was smoking.

"It's too bad," ruminated Ralph, as he left the place, shaking his shoulders as if to cast off a spatter of filthy mud. "It is a terrible warning, too," he continued. "Thank Heaven for mother, home, and principle! Maybe those fellows haven't got all the blessings that keep me in the right path. I wish I could do them some good. Well, I won't do them any harm. Let Ike Slump go his way. I fancy the punishment he has got will keep him from troubling anyone around Stanley Junction for a while."

Ralph did not inform the local police of Ike's reappearance, nor did he lodge any complaint against Bemis.

He imagined that his visit to the latter had scared off his enemies, as two days went by and there was no further attempt made to obstruct his services at the switch tower.

Affairs there got down to a routine that pleased the young leverman. Not a jar or break in the service occurred. He seemed to have glided naturally into the details of the business, and was able to take it easier now. He did not worry about wrecks any more. Following out old Jack's definite instructions to always strictly obey orders and act promptly, he simply watched 'phone, dial, and levers. He let the limits tower and the yards switches take care of themselves.

It was three days after Ralph's encounter with Young Slavin and the fifth of his service at the switch tower.

His shift had been changed temporarily. It was divided into four hours in the morning and four in the afternoon.

Ralph had an hour for dinner. That especial day his nooning had something of the element of a new interest. His mother told him she had received a brief note from Mrs. Davis.

The latter in a penciled scrawl told Mrs. Fairbanks that the writer was not very well, and would like to have her call that afternoon. She said she wanted to pay back the ten dollars she owed Ralph, as she had received a remittance from her sister.

"Are you going to see her, mother?" inquired Ralph.

"Surely. I will run up to her house as soon as the dishes are washed."

"I hope she will tell you something about those bonds," said Ralph. "I shall be anxious to know the result of your call."

"What time will you be home, Ralph?" asked his mother.

"A few minutes after five," he answered, and started for work, his mind filled with all kinds of anticipations regarding his mother's visit to Mrs. Davis.

A crowd lined the out freight tracks as Ralph reached the depot yards.

A circus had come to town, and the menagerie vans had been switched on the street sidings early that morning.

Now the big circus wagons were unloading these, to convey them to the tent site up on the common.

Some of the cages were uncovered purposely to advertise the coming show. This had drawn a throng of excited urchins and the loungers from lower Railroad Street.

Ralph halted for a minute or two, watching the removal of some of the cages.

He moved up to one that was the center of a peering, engrossed crowd. Those present acted as though something was going on out of the common.

A person who seemed to be the manager of the show, and looking quite serious and important, was giving some instructions to half a dozen circus hands.

Three of these latter had armed themselves with long pikes. Another carried a pole with a crooked iron end, resembling a giant chicken catcher. A fifth had a stout rope with a chain end forming a halter. The last of the group carried an enormous wire muzzle.

They stood beside a car which held a strong iron cage. This was empty, and at one end its canvas covering was torn, and two of its bars were bent far out of regular position.

Ralph ran up against an old friend as he pressed on the outskirts of the crowd.

This was John Griscom, the veteran engineer who had impressed Ralph into service the day of his first railroading experience when the yards at Acton had caught fire.

Griscom was on his way to the roundhouse to get his locomotive in trim for a regular afternoon trip. His dinner pail swung from his arm. He was such a practical old fellow that Ralph wondered at his taking an interest in anything so trifling as circus excitement.

"What's the excitement, Mr. Griscom?" he asked.

"Animal loose."

"Indeed? When did it escape?"

"That's what's worrying the circus people. They don't know. They just took off the canvas cover of the cage to make the discovery. The train switched here before daylight. It was in the cage then, they say."

Here the six circus hands started out on the quest of the missing animal.

"Search the yards thoroughly," ordered the menagerie manager. "Shoot, if you can't corner him. It won't do the show any good to have him do damage or scare people. Fifty dollars' reward for the capture of the beast!"

"What kind of an animal was it?" Ralph asked of Griscom.

"Toothless old bear, I suppose, or a blind lion," bluffly answered the railroad veteran, who did not have a very high opinion of the average circus wild beast.

Just here the menagerie manager seemed to discover an opportunity for advertising the show and lauding its attractions.

"I beg of you, gentlemen," he said, in a suave tone, as the crowd made a move to follow the searching party--"don't impede our efforts by getting in the way. Calcutta Tom, the largest and fiercest Indian tiger in captivity in any menagerie in the country, is loose. This superb king of the forests killed five men before he was caged, was brought to this country at a cost of six thousand dollars, and, if captured now, will be on exhibition this afternoon, along with the most marvelous aggregation of brute and human celebrities on the face of the civilized globe to-day."

"And all for twenty-five cents--lemonade and popcorn a nickle extra," piped a mischievous urchin.

CHAPTER IX--CALCUTTA TOM

Ralph walked in the direction of the switch tower.

He noticed that all the tracks seemed unusually inactive, even for the noon hour. The main rails were perfectly clear, and a good many locomotives were on the sidings.

Glancing up at the switch tower, Ralph was a good deal surprised to notice that it was entirely unoccupied.

This was startling. Ralph had never known that post of the service to be untenanted at any hour of the day or night.

Then he noticed on the out main rails near the tower a handcar. A trackman stood with his hands on the pumping bar. One foot on the car, his watch in his hand, old Jack Knight was looking impatient and excited.

"Hustle, Fairbanks!" he shouted, and Ralph came up on a sharp run. "Here," spoke Knight, extending a slip of paper to Ralph. "Get down to the depot master, double-quick. Then hustle back to the tower. I'm bound for the limits tower, to keep things straight there."

"Why, what's up, Mr. Knight?" inquired Ralph.

"Mile-a-minute special from the north, due at 1.15. You've got fifteen minutes. The out tracks are set for the 1.05 express all right. Soon as she passes, set the out main after her so the special will take the in tracks to the limits. No. 6 will wait at the limits while we shoot the special to the out again."

"A special?" repeated Ralph, in some bewilderment, "and from the north----"

"Obey orders," interrupted Knight crisply. "Nothing to move except the express till the special passes. Understand? Don't lose any time. Get that slip to the depot master, and hurry back to the tower."

"All right," spoke Ralph promptly.

He started on a run for the depot, as Knight sprang to the handcar and it was whirled down the rails.