Opera Stories From Wagner

By

Florence Akin

With Illustrations

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Opera Stories from Wagner, by Florence Akin This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Opera Stories from Wagner Author: Florence Akin Release Date: July 24, 2004 [EBook #9456] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OPERA STORIES FROM WAGNER *** Produced by Project Gutenberg Distributed Proofreaders

The verses printed in this book are quoted from Dr. Oliver Huckel's translations of The Rhine-Gold, The Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung, by the kind permission of the publishers, Messrs. Thomas Y. Crowell & Company. An occasional sentence in several of the stories is borrowed from the same source.

The Rhine-Maidens And Alberich

|

|

Wotan

|

|

He Tugged In Vain

|

|

Walküre

|

|

Siegfried

|

|

"Eat Him, Bruin," Laughed Siegfried

|

|

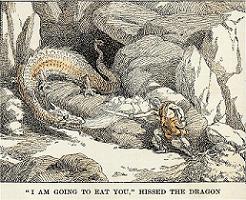

"I Am Going To Eat You," Hissed The Dragon

|

|

Three Norns Came To The Mountain Crest To Spin

|

In these stories you will find some wonderful giants.

You will find beautiful maidens who lived in a river.

You will find a large family of little black dwarfs who lived under the river, and you will find a splendid hero.

The little children of Germany used to curl up in their mothers' arms, when bedtime came, and listen to the stories of these strange people.

When these little children grew up, they told the same stories to their children.

So it went for many, many years.

The stories have been put together by a man named Richard Wagner. He put them together in such a way that they make one long and wonderful story.

After he had told these stories in words, he told them again in a more beautiful way. He told them in music.

Sometime you will hear this music, and you will think of beautiful water-maidens, singing and dancing in the sunshine.

You will think of great giants walking over mountains.

You will think of the little black dwarfs under the river, and you will hear them hammering, hammering upon their anvils.

In the Rhine River there lived three beautiful maidens. They were called the Rhine-daughters.

They had long, golden hair, which floated upon the waves as they swam from rock to rock.

When their father went away, he left in their care a great lump of pure gold.

This gold was on the very top of the highest rock in the river.

Every morning the beautiful Rhine-daughters would dance and sing about their gold.

They sang a happy song:--

"Heigh-ho! hither, ye waters!

Waver and waft me to sleep on your breast!

Heigh-ho! hither, ye waters!

Weave me sweet dreams on your billowy crest!"

One morning, when the sun was shining very brightly, the Rhine-daughters were startled by a strange sound in the depths of the water.

"Look!" whispered one. "What is that scowling at us from the rocks below?"

There, stealing along the river-bed, they saw a hideous little black dwarf.

"Who are you, and what do you want?" asked the Rhine-daughters.

"I am Alberich," answered the dwarf as he tried to climb up on the slippery rocks. "I came from the kingdom of the Nibelungs, down under the earth."

"What!" said the Rhine-daughters. "Surely you do not live down in the dark earth where there is no sunshine?"

"Yes," answered Alberich. "But I have come up to frolic in the sunshine with you"; and he held out his ugly, misshapen little hands to take the hands of the Rhine-daughters.

They only laughed at him and darted away to a higher rock.

Alberich hurried after them.

He blinked and scowled in the sunshine, because his eyes were not used to the light.

The maidens laughed and shouted in their play.

They called to Alberich and teased him.

They went very close to him, pretending that they would take his hand, that he, too, might play in the sunshine. Then they would quickly dart away, mocking him, and laughing at him more loudly than ever.

Alberich grew fierce and angry.

He clenched his fists and cried:--

"Woe be to you if I should catch you now."

Alberich was the most hideous of all the black, ugly little Nibelungs.

The Nibelungs had cross, scowling faces, because they were always scolding each other.

They quarreled from morning till night, so, of course, their faces grew to look quarrelsome and ugly.

As Alberich hurried after the Rhine-daughters, he suddenly caught sight of the gold glittering in the morning sun.

He stood still. Then he straightened up as tall as his crooked, misshapen little back would let him. He opened his eyes wide.

"Oh! Sisters! See how Alberich is staring at our gold!" whispered one of the Rhine-daughters. "Perhaps this is the foe of which our father warned us. How careless we have been!"

"Nonsense," answered one. "Who would fear this little black fellow? He will do us no harm. Let him gaze upon the gold. Come, let us sing!"

The maidens joined hands and circled about the gold, singing:--

"Hail to thee! Hail to thee!

Treasure most bright!

Rhine-gold! Rhine-gold!

Beautiful sight!

"Hail to thee! Hail to thee!

Out of the night!

Rhine-gold! Rhine-gold!

Wakened so bright!"

Still Alberich stood and stared at the gold.

"What is it?" he gasped. "What is it?"

The Rhine-daughters shouted back to him:--

"Heigh-ho! and heigh-ho!

Dear little imp of woe,

Laugh with us, laugh with us!

Heigh-ho and heigh-ho!"

But Alberich did not laugh with them.

He would not take his eyes off the gold.

"That," said the maidens, "is our Rhine-gold."

"A very pretty plaything it is," said Alberich.

"Yes," replied the careless sisters, "it is magic gold. Who moulds this gold into a ring shall have all power upon the earth, save love."

Alberich muttered to himself: "What do I care for love if I have all the gold I want?"

Then he sprang upon the slippery rock and snatched the gold. With one wild leap he plunged into the depths below.

Down, down he went to his deep, dark kingdom, clutching fast the precious gold and muttering:--

"Now all the earth is mine. It is mine, all mine. Now I shall rule the world."

Poor foolish Alberich! He did not know that the best things in this world are the things which gold cannot buy.

The power of love is greater than the power of gold.

The maidens shrieked and screamed: "Our gold! Our gold! Our precious gold!"

Too late! Far, far below, they heard a laugh, the rough, rude laugh of Alberich, the dwarf.

After that, when the Rhine-daughters came to the rock where the gold had been, they could not sing their happy song.

Their faces were very sad now, and they said: "Oh, why did Alberich steal our beautiful gold? It cannot make him happy, for no one can ever be truly happy who does not know love."

They often sat upon the rocks in the dusk of the evening and cried as if their hearts would break because they had lost their gold.

"The black waves surge in sorrow through the depths, And all the Rhine is wailing in its woe."

On a mountain-side, above the banks of the Rhine, lived a family of splendid giants.

The greatest of the giants was Wotan. He was the king.

They had always lived out of doors, because the king had never been able to find a giant who was large enough to build such a grand castle as he wanted for his family.

But one day there came to the mountainside the largest giant Wotan had ever seen.

His name was Fafner.

He was many times larger than Wotan.

Wotan told Fafner how much he wanted a wonderful castle.

Fafner said: "I will build such a castle for you if you will give me your sister, Freya."

Fafner wanted to take the beautiful Freya to his own country.

Wotan did not stop to think what an awful thing it would be to lose Freya.

His thoughts were of nothing but the wonderful castle.

"Build it, Fafner," said Wotan.

That night Wotan and his family lay down upon their mountain to sleep.

Wotan dreamed of a wonderful stone castle with glittering towers.

He dreamed he saw the castle gleaming in the morning sun.

It was morning in the beautiful country where the Rhine River flows.

The giants upon the hillside were just awakening from their night's sleep.

During the night Fafner had built the wonderful castle.

Wotan's wife was the first to see it.

"Awake, Wotan! Awake!" she cried.

As Wotan opened his eyes he saw the castle upon the summit of the mountain.

What a great shining castle it was!

In delight Wotan cried: "'T is finished! And my glorious dream is true!"

All night long Fafner had toiled hard.

He finished just as the morning dawned.

He was waiting now for Wotan to awaken and to give to him the beautiful Freya.

He would take her and hurry to his own country.

"While you slept I built the castle," said Fafner. "Now I am ready for the payment."

"What payment do you want?" asked Wotan.

"What payment do I want?" shouted Fafner. "Surely you have not forgotten your promise? The price was Freya, and I shall take her home with me."

"Oh, that was only in jest," said Wotan. "I could not think of letting Freya go. But I shall pay you well for the castle. I shall give you something else that will be just as good for you."

Fafner grew very angry and screamed:--

"Cease your foolish talk. I built your beautiful stone palace. I drudged and toiled and heaped the massive rocks. Each stone lies firm and solid in its place, and I will have my pay!"

"But, surely," said Wotan, "you did not think I meant to give you Freya? 'T is she who feeds us golden apples. No one but Freya knows how to make them grow. If it were not for her fresh fruits my family would grow old. They would wither like the autumn flowers."

"Yes," raged Fafner; "I know it is fair Freya's golden apples that keep you young. But now Freya belongs to me. Nothing else will I have."

Just then Wotan saw his brother, Loki, coming over the mountain.

"Wait, Fafner! Wait until I can talk with my brother about this!"

"Loki, why are you so late?" complained Wotan, when Loki came.

Loki was much excited.

"The Rhine-daughters are in great trouble, Wotan. As I was coming by the river I heard them weeping and wailing. Black Alberich has stolen their gold, and I promised them that I would tell you about it. Perhaps you could help them."

"I have no time for the Rhine-daughters now," said Wotan. "I have trouble of my own. Tell me how I can save poor Freya!"

For many years Fafner had heard of this lump of gold. So he listened to all that Loki told. Then he asked: "Why does Alberich want the gold?"

"Because," replied Loki, "the gold can be made into a magic ring; if the one who would make the ring will forever give up all love, the magic ring will make its owner master of the whole wide world. Alberich declared that love was nothing to him if he could have all the gold he wanted."

To himself Fafner thought: "Perhaps it would be better for me to have the gold than to have Freya and her golden apples." Then aloud he said: "Let me tell you what I am willing to do, Wotan. If you will get that gold for me, I will accept it in place of Freya."

"You rascal!" roared Wotan. "How can I give you gold that is not mine?"

"Very well," said Fafner. "I did not come here to quarrel. Already I have waited too long. I shall take my pay. Come, Freya, you must go with me."

Poor, frightened Freya wept and cried aloud as Fafner picked her up and carried her off over the mountain.

He called back to Wotan and Loki: "I will keep Freya until evening. Then I shall come again, and if you have that glittering Rhine-gold for me, then you may have your sister. If you do not give me the gold, then Freya is mine and I will keep her always."

As soon as Freya was gone, the flowers began to droop their heads.

Wotan and his family began to grow old and gray.

It seemed to Wotan like some awful dream.

Suddenly Loki cried out: "We have not eaten Freya's fruit to-day! Now she is gone, we shall all wither and die!"

Wotan had stood gazing at the ground, trying hard to think what he could do to save himself and his family.

"Come, Loki," he said. "We must go to the deep dark kingdom of the Nibelungs. I must have the gold! Let us go by way of the brimstone gorge. I cannot go by way of the river. I do not want to hear the wailing of the Rhine-daughters."

Wotan called back to his anxious family: "Only wait till evening and I promise I shall bring your lost youth back to you."

"Far, far below the ground are gloomy depths,--

A mighty cavern, rocky, dark and vast."

It was as dark as night down in the kingdom of the Nibelungs, except for the light which flared from the smoking torches, or glowed in the coals upon the anvils.

The family of dwarfs were skilled blacksmiths and metal-workers.

From every little niche and corner came the sound of clinking anvils. Before Alberich stole the gold, the Nibelungs often sang as they worked.

They sometimes made pretty ornaments for their wives to wear or toys for their little children.

But now Alberich had made the ring of gold which bound them to do his will.

He had no love in his heart, so he drove and scolded all the time.

He made them work, work, work, both day and night, and all that they made belonged to him.

So Alberich was daily becoming mightier than ever.

Mimi, who was Alberich's brother, was the best smith in all this swarm of black slaves.

Alberich forced Mimi to make for him a strange wishing-cap.

It was made of woven steel.

Mimi had to make it just as Alberich said, but Mimi did not know how it was to be used. When it was finished, Mimi feared it had some wonderful power, and he did not want Alberich to have it.

He wished he might keep it for himself.

He had worked hard to make it.

"Give me that helmet," said Alberich. "I want you to know, Mimi, that everything in this cave belongs to me!"

Mimi had to give it up.

Alberich put it on his head. "Now I shall see what magic there is in this wishing-cap. Come, Night and Darkness!" he called. "Make me so no one can see me!"

In an instant he was gone, and there was only a cloud of smoke where he had stood.

"Now, Mimi!" he called, "look sharp! Can you see me?"

"No," gasped Mimi. "I cannot see you at all."

The cloud of smoke moved down the gloomy cave and Alberich's cruel voice laughed: "Ha! ha! Now I shall make you black slaves work! Now you dare not be idle, for when you do not see me I shall be watching you!"

His voice sank deeper. "Now I will make you dig, dig, dig, to the very depths of the earth to bring me gold!"

Mimi was so frightened.

When the cloud of smoke had gone out of sight, he lay down upon the rocks and cried.

Wotan and Loki swung themselves over the ledge and slid down into the murky cave where Alberich lived.

Wotan looked around and said:--

"So this is the Kingdom of the Nibelungs! What an awful place it is!"

From far down the passages came the sound of hundreds of slaves melting and welding precious metals for their master.

"Loki," said Wotan, "I believe it is always dark and gloomy where there is no love. What is that strange cry I hear?"

"Ho, Mimi, is that you?" said Loki. "Leave me alone!" cried Mimi.

"Then tell me what you are crying about?"

"Oh," replied Mimi, "that wretched Alberich, with his ring of gold, has made us all his slaves! With it he drives us down into the earth to dig more gold. What we get is all his. We slave for him both day and night.

"This curse of gold has filled our cavern with despair. Lately he made me forge a wishing-cap for him. With it he makes himself so none can see him. Now we slaves can never rest. Sh! sh! He is coming now!"

Wotan and Loki, peering through the darkness, could see him now and then as he passed under the light of a flaring torch.

He was driving a swarm of bent black slaves who were carrying great packs of gold and silver and precious ore upon their backs.

The helmet was hanging at his waist.

In his hand he was swinging a whip and the giants could hear him yelling:--

"Pile up the gold! Hurry! Hurry, you lazy rogues!"

Suddenly Alberich saw the giants.

"Who is this that dares come into my cave?" he cried. "Mimi, get back to your work!"

Then to all the other slaves he called:--

"Get below, every one of you! Crawl into your dingy shafts and dig the gold! Begone, I say! You must obey the master of the ring!"

As soon as the black swarm had crept away, Alberich spoke angrily to Wotan and Loki. "What do you want in here?"

"We just came to see you," said Wotan. "We hoped you might be glad to have us. We think you must be a very clever man. We have heard a great deal about the wonderful things you can do."

This pleased Alberich. He grew very proud and began to boast.

"See all this gold of mine!" he said.

"Yes," answered Loki; "it is the most gold I have ever seen, but what use is it? It does no one any good in here where nothing useful can be bought with it."

"I am heaping it up," said Alberich. "Some day, with this same treasure, heaped and hid, I hope to work some wonders. You shall see! I shall be master of the whole wide world! Ha! the smoke of Alberich's kingdom shall smudge even your flowery mountain-sides and your sparkling rivers. Everybody shall be my slave! Beware of this black Nibelung, I say, for he shall rule the world!"

Loki was very sly and cunning. While Alberich boasted, he was planning how he might trick the dwarf and take his gold.

To Alberich he said: "Surely, you will be the mightiest of men. But suppose that while you sleep, one of your slaves should creep upon you and steal your ring?"

Alberich smiled. "There is no danger of that," he said. "I will show you a trick or two. Do you see this helmet? It is a magic helmet. With it I can make myself so no one can see me, or I can change myself, quick as a flash, into anything I wish to be. So, you see, I am perfectly safe."

"I never heard of such wonders," answered Loki. "I really cannot believe it."

"I shall prove it to you," said the dwarf, never dreaming that the sly Loki was only laying a trap for him. "What form will you have me take?"

"Turn into anything you wish. Only let me see it done and then I shall believe."

Alberich put on the helmet. "Ho! Monster Dragon, come!" And quick as a flash he turned into a huge dragon.

Loki pretended to be frightened. As the fierce monster squirmed toward him, he made believe that he was going to rush from the cave.

The dragon vanished and there stood Alberich again.

"Now do you believe?" he asked.

"Indeed, I do," replied Loki. "It is wonderful. But if you could shrink to some tiny thing, it would be even much more clever, because you could creep into a crevice and spy upon your enemies. But, of course, getting small would be too hard a thing to do."

"Only tell me what you would have me be," said Alberich.

"Now I shall catch him," thought Loki. "Could you make yourself as little as a toad that quickly slinks under the rock when there is danger near?"

"Ha! Nothing easier," laughed Alberich.

And again putting the helmet on his head he coaxed:--

"Come, little toad! Creep from your cranny!" Alberich was gone, and there at Wotan's feet hopped the tiny toad.

"Quick, Wotan!" cried Loki.

And in an instant Wotan put his heavy foot upon the toad.

Loki reached down and took the magic wishing-cap.

As soon as the cap was off, the toad disappeared, and there lay Alberich, held fast by Wotan's giant foot.

"Let me go!" shrieked the dwarf. "Take your foot off of me, this minute!"

Wotan calmly answered: "You may go when you have promised all I ask."

"Then what do you want?" groaned Alberich.

"I want all your glittering gold," said Wotan.

Alberich held the ring close under his breast and muttered to himself: "They may have the gold! What do I care! With this ring I can soon make my slaves dig more."

Then aloud he said: "You may take the gold. My slaves shall heap it at your feet."

He slyly slipped his hand to his lips and, kissing the ring, called his slaves with its magic.

In a moment the little black Nibelungs came in swarms from every shaft, bearing the precious gold.

Alberich did not like to have them see him under Wotan's foot.

"Heap up the treasure!" he yelled. "Don't stop to stare at me. I am still your master. Now, crawl back into your shafts and drudge. I am coming in a minute, and it will not be well for you if I do not find you digging!"

Trembling with fear, they scurried to the darkest depths.

"Now, there is your gold!" said Alberich. "Give back my helmet and let me go!"

But Loki quickly tossed the helmet upon the shining heap.

"Take it, then," snarled the dwarf, thinking he could easily, with the power of the ring, force Mimi to make another, "but let me go, I say!"

"Just wait a minute, Alberich," said Wotan. "That ring I saw glittering on your finger,--I must have that too."

"The ring!" Alberich screamed in horror. "No, you shall never have the ring!"

Wotan's face grew stern.

"That ring does not belong to you. You stole its gold from the Rhine-children," he said.

"Think twice, Wotan, before you take this ring from me! I warn you now a curse goes with it."

But Wotan drew the ring from the dwarf's finger, then set him free.

"Farewell, Alberich! Farewell!"

"Ha!" laughed Alberich in scorn. "It will never bring you happiness. Its owner shall always feel its curse of care, sorrow, and unrest."

Then, turning, he groped his way down the cavern, far poorer than the day he went stealing along the slippery bed of the river. Then, he had no gold. Now, he had no gold and no friends.

Wotan and Loki hurried back to the mountain-side with their treasure.

At the same time Fafner returned, bringing Freya.

Already Fafner had made up his mind that if he gave Freya back, he must have a very great deal of gold.

When Freya again reached her own country, the sun grew brighter, the air grew sweeter, and the glow of youth came back to the cheeks of Wotan and his family.

"Here, Fafner, is your gold!" great Wotan cried.

"I am sorry to give Freya up," said Fafner. "Pile up the gold between her and me. You may keep her if there is gold enough to hide her completely from my sight. So long as I can see her, I cannot part with her."

Then Wotan and his family heaped the glittering gold. They piled it as loosely as they could, but when they had put on all the gold they had, the greedy Fafner cried:--

"More, more! It is not high enough! Still I can see fair Freya's shimmering hair. Throw on that shining helmet!"

"Put it on, Loki," commanded Wotan. "There, Fafner, is your pay. Freya again belongs to me."

"Not yet!" cried Fafner, as he peeped through a space in the heap. "I can see her eyes through here." Then, pointing to the ring on Wotan's finger: "Bring that ring and put it in this space."

"Never!" cried Wotan.

Then Loki spoke. "The ring belongs to the Rhine-maidens, and Wotan is going to return it to them. Already we have given you more than you should expect, all that shining heap and the helmet besides."

"I will not give you any more!" roared Wotan. "Not all the mighty world shall take this ring from my finger!"

"Then I shall be gone," said Fafner. "I was afraid you would not give me enough gold. Freya is mine forevermore."

Wotan's family began to plead for Freya. "She is worth more to us than all the gold in this world! Without her we must all wither and die!"

It was no use to resist. Wotan knew that he dared not lose Freya.

Taking the ring from his finger, he flung it upon the shining heap.

Fafner gathered up the hoard--the hoard for which he had worked--the hoard for which he had made so much trouble.

He carried it off to his own country. Now that he had it, he had no thought of using it.

He wanted it merely for gold's sake; not for the sake of the great, good things that might be done with it. The only thing he wished to do was to keep others from getting it.

He heaped it up in a cave in the forest. Then he put on the helmet and changed himself into a fierce, ugly dragon.

For the love of mere gold he was willing to give up being a splendid giant, who roamed freely over the beautiful mountains, and to become a hideous, twisting, squirming monster.

The rest of his life he would lie at the door of the cave and guard the treasure. The treasure should lie there useless to all the world.

Fafner,--a slave to gold!

As Fafner carried away his treasure, a great storm gathered over the mountain crest.

The sky grew black. The thunder rolled. Its echoes bounded on from cloud to cloud, from peak to peak, then rumbled down the valleys to the sea.

Then the clouds drifted away. The setting sun shot its long rays into the deep valley.

There, arching over the river and reaching from the flowery mountain-side to the very door of the gleaming castle, stood a shining rainbow bridge.

"Lo! our castle! Our beautiful Valhalla!" cried the king. "Let us cross over. It shall be our dwelling-place forevermore."

One by one they stepped upon the bridge.

As Wotan walked slowly and sadly over, he heard the wailing of the Rhine-maidens in the river below:--

"Rhine-gold! Rhine-gold!

We long for your light!"

"I shall never be happy again," thought Wotan. "I have given my honor for Valhalla. What an awful price I have paid!"

Many years passed. The giants lived on in their beautiful Valhalla.

But their king was sad.

He could not forget Alberich's curse. What if Alberich should in some way gain possession of the ring again! He would destroy Valhalla.

"Oh, why was I not brave enough to give the ring back to the Rhine-children!" sighed Wotan.

"If only it might again be a mere thing of beauty to gladden their hearts, but so long as it is in the world, how many more will it not rob of their happiness.

"Surely, some great hero must come who will be brave enough to slay the dragon and give the ring back to its rightful owners."

Said Wotan to himself, "I shall make a mighty sword, and when the hero comes, his sword will be ready for him."

Then the great Wotan wrought a matchless sword.

When it was finished, he took it and went into the forest. Straight he went to the home of the bold robber Hunding.

It was a beautiful moonlight night when he reached Hunding's hut.

From the loud laughter and shouting that Wotan heard as he neared the hut, he knew that Hunding and his friends were having a merry feast.

Wotan lifted the latch and entered.

The great, rude room was built around the trunk of a mighty ash tree.

The walls were made of roughly hewn logs.

The floors were covered with the skins of wild animals of the forest.

Mats of reeds and grasses hung upon the walls.

The huge fireplace was built of rough stones.

The mighty Wotan scowled upon the crowd.

Then, lifting the gleaming sword above his head, with one great lunging blow, he buried the bright blade, even to its hilt, in the great ash tree's quivering side.

Then, turning to the guests, he said:--

"The sword shall belong to him who can draw it from the ash tree's heart."

Though each guest tugged with all his might, he tugged in vain.

In the years that followed, many came and went, and all tried hard to gain the sword, and still that magic blade slept on within the ash tree's sheath.

One very dark and stormy night, Siegmund, a brave warrior, wandered alone in the forest.

That day a desperate battle had been fought.

As the darkness came on, Siegmund escaped from the enemy.

He had lost his weapons, and now he trudged through the pathless woods, seeking some place where he might find balm for his wounds and shelter from the raging storm.

He was almost exhausted when he caught sight of a flickering candlelight in the window of a forest hut.

With the little strength that he had left, he dragged himself to its door.

No one answered his call, and no longer caring if it were the home of friend or foe, he opened the door, and staggering in he sank upon the hearth.

As he looked about him he thought, "This is the home of some forest chief."

A great fire burned in the rude fireplace, and, as he grew warm, being worn and weary, he sank into a heavy sleep.

As Siegmund slept, the door of the inner room was gently opened and a beautiful woman stole softly in.

She was clad in snowy white.

Her head was crowned with a wealth of golden hair.

She had heard Siegmund as he entered the room, and, thinking her chieftain had returned from the hunt, she came to greet him.

Instead she saw a stranger on the hearth, and, drawing near, she saw that his face looked sad and troubled.

"Who are you?" she asked, but Siegmund did not stir.

Then she knelt beside him and looked into his face.

It was the strong, noble face of a hero.

"He sleeps," she said. "How weak and weary he seems. Perhaps he has been wounded or is faint from hunger."

Siegmund roused and asked for water.

The woman ran quickly, and, bringing a cup of cold water, held it to his parched lips.

Siegmund drank. Then, gazing into the woman's kind face, he gasped: "Where am I?"

But, with a startled look, she stood in silence, listening to the heavy tread outside the door.

The next moment the chieftain entered and glared fiercely at Siegmund.

The woman hastened to say: "I found this stranger lying on our hearth. He was faint and needed help."

"And did you give it?" growled the chieftain.

"I gave him water. I could not drive him out into the stormy night."

The chieftain grew dark with anger as he said: "Because it is the sacred law of my country that none shall be turned from the door who seek shelter from the night, this intruder may stay until the morning. Then he shall fight for his life."

Siegmund knew now that he was in the house of the fierce Hunding.

Taking the woman by the arm, Hunding led her from the room, and Siegmund was left alone to think how he might save himself.

Long he leaned upon the hearth in troubled silence. Then, knowing he must flee, he turned toward the door.

That moment the last flickering light of the dying fire flashed upon the hilt of the magic sword in the ash tree.

Siegmund saw it, and, springing forward, he grasped its hilt. Then, bracing himself against the tree, with one mighty pull, behold! he drew the bright blade from its sheath.

Wotan gathered to Valhalla a company of nine war-maidens. They were called the Walküre.

They were strong, beautiful young women, who rode through the clouds upon swift horses.

The horses could not only run on the ground; they could fly through the air.

The maidens wore wings upon their helmets, and each wore a splendid silver armor which glittered and flashed in the sunshine.

Wherever there was a battle on the earth, Wotan would send a battle-maiden for the most valiant hero on the field.

The maiden would fly over the battlefield and watch while the warriors fought.

When the bravest man was wounded, she would quickly swoop down, and, snatching him up, would fly with him to Valhalla, where he was revived by fair Freya.

Sometimes, when evening came, every one of the war-maidens rode into Valhalla carrying a noble hero.

This was Wotan's plan for protecting the palace.

After a while he would have at the castle a company of the bravest heroes of the earth.

He hoped he would then be happier.

The heroes would protect the beautiful Valhalla in time of danger.

Morning dawned.

The king of the giants went forth from his castle and called Brunhilde, his favorite battle-maiden.

He loved Brunhilde more than any other of the Walküre.

She was the bravest of them all.

He loved her as a father loves a daughter.

"Brunhilde," said Wotan, "to-day there is to be a fearful battle. The fierce Hunding is to fight with my dearest friend--the valiant Siegmund.

"Long have I wished to have my noble friend at Valhalla. Fly, Brunhilde, to the battlefield. Give to Siegmund the victory. Carry him here to dwell upon the heights."

At that moment Wotan's wife rushed to them in great anger.

"Wotan," she cried, "Siegmund must not be brought to Valhalla. I ask that my friend, the forest chief, shall be given aid. Send Brunhilde to bear Hunding to our castle."

"No," replied Wotan, "I must protect Siegmund. He it is who won my sword."

"Take the sword from him," replied Wotan's wife in rage. "I plead for Hunding's rights. Promise me that you will forbid your war-maiden to give aid to Siegmund."

Wotan's heart ached at the thought of failing this friend he loved so well.

On Siegmund were centered all his hopes. Yet he feared to refuse his wife's request.

Quarrels and strife must not come into Valhalla.

He threw himself upon a rocky seat and hung his head and thought in silence.

At length he said:--

"I promise. From Siegmund I withdraw my aid."

Now that Wotan's wife had gained his promise, she turned back to Valhalla.

Wotan buried his face in his hand and cried out in despair:--

"Oh, woe and shame upon the giants! What I love best I must give up. I lose the friend I hold most dear. All my hopes are vanishing. A short time and the giants will be no more."

Loudly he moaned: "This is the curse that clutched me when I snatched the glittering gold."

Brunhilde knelt at Wotan's feet, and, looking into his sad eyes begged:--

"Tell me, Father, what thy child can do. Trust me, Father!" she pleaded. "Tell me all your woe."

Wotan took her hands in his and told her the story of the ring.

How he had taken it from the finger of the dwarf.

How he had stooped to trickery and had stolen the gold with which to pay for Valhalla.

He told of the sad hearts of the Rhine-daughters, and of the greedy Fafner, lying at the door of his forest cave, guarding his hoard.

But last of all, he told of the dread of Alberich's curse.

He told of his fear that the black Nibelung might regain the ring and by its power destroy Valhalla.

When Brunhilde had heard the story of the curse, she said:--

"But, Father, Alberich could not destroy Valhalla. Think of all the heroes gathered there. Surely, they can protect it from all danger."

"Brunhilde, my child," sighed Wotan, "you do not know the power of that ring when it is in the hands of Alberich. Once he gains it, he can do with it what he will, because he has given up all love. With it, he could turn my friends into enemies. Our heroes would then fight for Alberich.

"I have long hoped that a hero might come who would be brave enough to slay the dragon. I hoped it might be Siegmund. But now I must desert him in his time of need. Though it breaks my heart, I must give him up.

"Darkness and gloom are fast gathering upon Valhalla. Go, Brunhilde. Go quickly to the battlefield and shield my wife's friend."

"No, no, Father, I cannot!" cried the battle-maiden. "You love Siegmund, and I shall guard him well."

At these words the mighty Wotan grew wrathful and cried:--

"How dare you disobey me, child? Go, I say! Give to Hunding the victory, and thus fulfill my promise."

Sadly Brunhilde took up her spear and shield and rode away to the battlefield.

Closely Brunhilde watched the struggle.

When she saw how fairly and valiantly the noble Siegmund fought, and how unfair and cowardly was the wicked Hunding, she thought:--

"I shall obey my king's wishes, not his words. He loves Siegmund."

She hovered nearer as the battle grew more terrible.

Suddenly she dashed to Siegmund's side and cried:--

"Slay him, Siegmund, with your matchless sword!"

Siegmund raised his sword to deal the deadly blow, when lo! Wotan dashed through a rift in the clouds and struck Siegmund's sword with his mighty spear.

The sword fell in pieces at the feet of Brunhilde. The victory belonged to Hunding.

Brunhilde, terrified by the angry Wotan, snatched up the broken pieces of the sword, and, springing to her saddle, dashed away.

Faster and faster she fled to the forest, bearing the broken blade to Siegmund's wife.

"Siegmund is slain!" she cried. "These are the pieces of his mighty sword. Keep them for your son, Siegfried. He will be brave like his father.

"Yes, Siegfried will be the bravest hero the world has ever known."

Then, springing again to her saddle, she fled toward the mountains.

"On! on! my fiery steed!" she urged.

No battle-maiden ever rode so fast.

If she could but reach the other battle-maidens before the wrathful Wotan overtook her, surely, they would protect her from his anger.

It was the custom for the battle-maidens to meet at Walküre Rock every evening at sunset. This was the highest peak in the mountains. From here they would ride into Valhalla, each carrying the hero whom she had snatched from the battlefield.

"Heiho! hoyotoho! heiho!" called each as she neared the peak, and "Heiho! hoyotoho! heiho!" came the answer.

At length all but one had reached the rock.

"Why does Brunhilde not come?" they asked of each other anxiously.

"What has happened that she should be so late?"

Loudly they called: "Heiho! hoyotoho! heiho!"

Looking toward the valley, they saw Brunhilde riding fast.

Her horse was flecked with foam.

"Heiho! hoyotoho! heiho!" they shouted; and "Heiho! hoyotoho! heiho!" came Brunhilde's answer.

She reached the peak and sprang from her saddle, crying:--

"Help me, Sisters! help me! I disobeyed our king!"

Even as she cried Wotan drew near.

"Where is Brunhilde?" he screamed in anger.

The skies grew black with the storm of his wrath.

"Every one of you who dares to shield her shall share her punishment."

Brunhilde, weeping, walked out from her hiding-place among her sisters.

Sinking at Wotan's feet she cried:--

"Here I am, Father. What punishment is mine?"

Wotan spoke in solemn tones:--

"Never again shall you see the beautiful Valhalla. Never shall you carry another hero to your king.

"You shall lie down upon this mountain peak, and here you shall sleep until some wanderer in passing shall awaken you, and his wife you shall be."

"You cannot mean it, Father! Anything but this! Never to see Valhalla? Never to ride with the Walküre? Father! Father! Take back these words of doom!" Brunhilde's sisters began to plead for her.

"Go!" he cried, "every one of you. Leave Brunhilde to me!"

Frightened by great Wotan's awful wrath, they spurred their horses and dashed away to Valhalla.

Slowly the storm clouds drifted away. The twilight came.

Still Brunhilde lay in fear and grief at Wotan's feet.

At length she lifted her sad eyes to Wotan and cried:--

"Was it so wrong, this thing that I have done? 'T is you who taught me to shield the brave and the true. I only sought to care for one you loved."

"Brunhilde, you disobeyed me. I have told you what your punishment shall be. I cannot change it."

"Then grant me, Father, this one wish: that you will make the place where I sleep so no coward can reach me. Make it so none but a hero will dare come near."

Then, taking Brunhilde in his arms, he said:--

"I grant your wish, my child. I shall encircle the place with magic fire. Only he who knows no fear may claim you for his bride."

Then Wotan kissed Brunhilde upon each eyelid, and she fell fast asleep.

Gently he bore her to a mossy mound beneath a spreading fir tree.

Laying her down, he looked long and lovingly upon her sweet, brave face.

He drew her helmet close over her eyes, and laid her shield upon her breast.

The flowers went to sleep.

Brunhilde's noble steed lay down and slept.

"Farewell, my child, most brave and beautiful!

Thou life and light of all my heart, farewell!

Pride of my soul, farewell, a long farewell!"

Wotan strode a few steps away from where Brunhilde slept, then struck the rock with his mighty spear.

Red flames shot up, leaping almost to the sky. They were magic flames and would not harm any one.

But they looked like real fire, and none but a hero would dare go into them.

They would frighten away all cowards.

Wotan walked around the peak, drawing a line with his spear.

From every place the spear touched the fire burst forth, until at length the mound where Brunhilde slept was entirely encircled by lurid flames.

Great Wotan looked upon his work. Then he turned and called to all the mountains and the valleys below:--

"Whoso dareth Wotan's spear,

Whoso knoweth naught of fear,

Let him burst these flames of war,

Let him leap this fiery bar!"

The cunning Mimi secretly longed to steal out into the world and find that magic ring.

One night when all the other little Nibelungs were asleep, he slipped stealthily to his forge.

He gathered up his best tools.

Making sure that all were soundly sleeping, he stole quietly out.

What surprise and excitement there must have been the next morning when the little black Nibelungs found that Mimi had run away and had taken all of his best tools with him!

How they must have rushed about, each anxious to tell another the news of the missing Mimi!

Of course, Alberich guessed very quickly for what purpose his brother had gone.

And how Alberich must have raged when he thought of what a sad day it would be for him should Mimi become owner of that ring!

Mimi was strangely clever.

He said to himself: "That ring is hidden somewhere in the forest. I will go there and search until I know who has it. Then I will find some way of getting it."

On he went, until he came to the darkest place in the woods.

The boughs overlapped each other, so much that almost no sunshine could get through.

Mimi liked this place. It was soothing to his eyes, so used to the darkness of the Nibelungs' cavern.

Mimi had found the very forest which he sought to find.

This was the one in which the dragon lay guarding the hoard.

The sly dwarf caught a glimpse of the huge monster lying at the door of its cave.

Its great yawning jaws and sharp teeth filled him with terror.

Mimi darted into the underbrush. How glad he was that the monster had not seen him.

He shook and trembled with fear as he peeped at the loathsome creature.

Its body was covered with green scales. Poison breath came from its nostrils.

Its awful snake-like tail twisted and lashed about. In the end of the tail was a deadly sting.

"Alberich's ring is in that cave," thought Mimi. "Now close to this forest I must find a good little cavern in which to live.

"Then I can come often to watch the dragon.

"Some day I shall find a hero to slay this fierce monster. Then I shall slink into the cave and snatch the ring.

"Ho! ho! my brother Alberich! We shall see who shall be master and who shall be slave!"

Mimi found a cavern in a rocky cleft. It was just the kind of place he liked.

In it was just the right kind of rock for a forge.

There he hammered at weapons or chains or whatever happened to be his need.

Daily he sneaked about in the underbrush, watching the dragon, and daily he became more anxious to gain the gold.

He was such a coward that he was frightened at almost every animal he saw in the woods and startled by every sound.

One day, when he had ventured farther from his cave than usual, he was startled by a strange little cry.

He listened a moment and thought:--

"It sounds like the cry of a little child. I shall run to my cave."

But as he heard the cry again, something made him want to see what it was.

He slipped cautiously through the bushes, in the direction from which the sound came.

When he reached the place he found a little baby boy.

This was the same forest to which Brunhilde had fled, bearing the broken sword to Siegmund's wife.

But now the mother had died, and Siegmund's child was left alone in the woods.

Mimi was mean and selfish.

He would not even have cared for a little child alone in the woods had he not thought that by so doing he might gain something for himself.

As he looked at the baby he heard a strange voice saying:--

"Siegfried is his name, and only he who knows no fear can mend the sword."

"The sword? The sword?" questioned Mimi. "What does the voice mean?"

Going nearer to the child, he saw close beside it the broken pieces of Siegmund's sword.

Mimi picked up the pieces and looked at them.

"The finest piece of steel I ever saw," he chuckled, as he ran his fingers carefully along the keen edges.

Then he cried aloud in joy.

"At last I have found the hero! This little baby is the son of some valiant warrior. These are the broken pieces of the warrior's sword. Such luck for Mimi!

"The boy will be a warrior like his father. I shall take him to my cave and take good care of him.

"When he is grown up I will make him pay me for my care and pains. He shall slay the dragon. Then I will take the ring."

He lifted the little baby as gently as he knew how, and started toward his cave.

Again he heard the same strange voice:--

"Siegfried is his name, and only he who knows no fear can mend the sword."

"Ha! ha!" chuckled Mimi. "That voice does not know what a skillful smith Mimi is.

"I will mend the sword and Siegfried shall use it to slay the dragon."

He folded the baby close in his rough, black little arms.

"A few more years, a few more years," he gurgled in glee, "and Mimi's hands shall clutch the precious gold."

Mimi took good care of Siegfried.

When the boy had grown large enough to play about in the woods, Mimi made for him a little silver horn.

Siegfried loved all the birds and the wild animals.

He knew they were his best friends, for something in Mimi's face always showed him that the dwarf was false.

Siegfried would wander out into the forest with his silver horn swinging from his shoulder.

He would blow his little horn song, and his forest friends would hear the call and come to play with him.

He watched the birds as they built their nests.

He listened to the father bird as he warbled his pretty little love songs.

How sweetly he sang to the mother bird while she sat upon the nest!

And when the little eggs had told their secret, both the father and the mother birds carried food to the babies.

Siegfried saw how tenderly the mother foxes, wolves, and bears cared for their babies.

From these friends in the forest he learned what love is.

Never for all the world would he have stolen one baby from its mother.

But it was when he watched the love-light in the eyes of the mother deer that he would shut his eyes and try to dream that he too had a loving mother.

Mimi always pretended to be Siegfried's father, and he pretended to love Siegfried.

But Siegfried knew there was no love in Mimi's heart.

Daily Siegfried grew larger and stronger.

Mimi continually boasted of his work at the forge.

Often he said: "No one in this world can make such marvelous swords as Mimi."

Siegfried urged him to make one sword after another, but as fast as they were made the boy would shatter them to bits with one blow on the dwarf's forge.

Then he would cry in disgust: "Nonsense, Mimi. Your swords are mere toys. Just like little switches.

"Either make me a good strong sword or quit your bragging."

Mimi always kept the pieces of Siegmund's sword carefully hidden. While Siegfried roamed through the woods, the dwarf would work for hours trying to mend the magic blade, but its hard steel would never yield either to his fire or his hammer.

Mimi grew tired and discouraged.

"I can never mend it," he groaned.

Siegfried grew to be a young man.

Often he saw his reflection in the water, and he said:--

"I am not Mimi's son. The babes in the forest all look like their parents. I do not look like Mimi."

Siegfried's reflection showed him a fearless face with large, honest eyes.

About the face fell a wealth of waving, sunny hair.

One day, as he studied this reflection and thought of the blinking, sneaking little black Mimi, he said:--

"I will endure his falsehoods no longer. I know he is not my father. This very day I am going to make him tell me who I am!"

Lifting his silver horn, he blew a loud blast.

Out of the woods came one of his good friends, a great brown bear.

"Come, Bruin," said Siegfried.

And he put a rope around Bruin's neck.

"We will go to Mimi's cave and we will make him tell us all we want to know."

Siegfried led the big bear to the mouth of Mimi's cave.

When the cowardly Mind saw the bear, he crouched behind the forge and screamed:--

"Take him away! Oh, Siegfried, take him away!"

"Eat him, Bruin," laughed Siegfried, as Mimi trembled with fear.

The bear growled at Mimi.

"Oh! keep him off!" gasped Mimi.

"I shall," said Siegfried, "if you will promise to answer all I ask."

"I will! I will! I will tell you anything you want to know," stammered Mimi.

Siegfried untied the rope.

"Good-bye, Bruin," he said, as he gave him a friendly slap on the back, and the big bear trotted off to the woods.

Mimi and Siegfried sat down upon the rocks in the cave, and Mimi told how he had found the baby in the woods and how he had brought him to the cave.

Mimi put in many words of how much Siegfried owed for all this care and trouble.

"Thou givest me always trouble and pain,

I wear to shreds poor foolish me!

Now, for my care, this is my gain,--

Only abuse and hate from thee."

Siegfried looked straight into Mimi's eyes.

He tried to see if Mimi were telling the truth.

"How did you know my name was Siegfried?" he asked.

Then Mimi told of the strange voice which said:--

"Siegfried is his name."

But not once did the dwarf mention the sword.

"You cowardly little wretch!" cried Siegfried. "You have told me so much that is not true that I can never believe you.

"How do I know that this is not another of your miserable falsehoods?

"Prove to me that this is true, or I shall make you sorry that you ever saw me. Prove it to me, I tell you!" cried Siegfried, as he grasped the shrinking dwarf by the shoulders.

"I will! I will!" gasped the frightened Mimi; and he brought out the broken sword.

Siegfried looked at the sword.

Then handing it back to Mimi, he said:--

"Mend it for me, Mimi! Mend it! Now is your chance to prove your skill!"

"I cannot! Oh, I cannot!" groaned Mimi; and he gasped out the rest of what the voice had told him:--

"Only he who knows no fear can mend the sword."

Siegfried took the broken pieces to the forge and began filing them to dust.

"Stop, Siegfried, stop!" cried Mimi. "You will ruin that blade!"

But Siegfried kept on filing.

He sang as he worked, until the pieces were filed to dust.

Then he melted the dust and poured the hot liquid into a mould the shape of a blade.

When it had hardened, he took it out and sharpened it.

Then he welded the blade to its hilt.

"Ha! ha!" chuckled Mimi. "At last the sword is mended.

"Now I will show Siegfried the dragon. He will not know a ring is in the dragon's cave.

"When the dragon is dead, the ring shall be Mimi's.

"Mimi, you are no longer the despised little Nibelung. You are the king of the earth."

Joyously Siegfried waved the bright blade above his head.

He brought it down with all his strength upon the forge, and with a mighty crash the huge rock fell in pieces.

Mimi sank in terror to the ground.

"Get up, you coward!" cried Siegfried.

"Now tell me what that thing is that I do not know. Fear? What is fear? Why did you not teach it to me?"

The wicked dwarf slipped to Siegfried's side.

"I will teach you. Come with me. I will show you a horrible serpent, lying at the door of Hate Cavern.

"There you will learn what fear is, if you can learn it any place in this world.

"Have you never seen anything that made you shiver from head to foot and made your heart beat fast?"

"I never have," calmly answered Siegfried. "Take me quickly, Mimi. I am ready to learn."

At every step Mimi chuckled to himself:--

"The ring is mine! At last the ring is mine! Now all the world shall kneel at my feet!"

"When he had gone as far as he dared, he pointed out the rest of the way to Siegfried.

"Just through here," he said. "And I shall go back now. When the dragon sees you it will be a terrible struggle! I shall wait anxiously for you, my Siegfried!"

But as Siegfried vanished from sight, he rubbed his black hands together and laughed:--

"Ah, it will be luck for Mimi if Siegfried and the dragon kill each other!"

When Siegfried had gone on a little way, he stretched himself upon a grassy mound beneath a tree to rest and think.

Looking up through the branches at the clear sky, he cried:--

"I am free! Free! Never again will I go back to that loathsome Nibelung."

A bird in the tree began singing its sweet wood-song.

"How do you do, my little feathered friend!" said Siegfried. "I am sure what you are singing is very sweet, but I cannot understand your words."

Then Siegfried cut a reed near by, and putting it to his lips, tried to whistle answers to the little bird's notes.

His music did not sound much like the song of a bird.

"I give it up, my little friend," he said, and threw away the reed.

"I will blow you a song on my silver horn," said Siegfried to the bird.

"I often blow this little song. It is my call for a comrade. I long for one. None better have ever come to me than the bears and foxes."

Loudly he blew his horn.

Soon there was a great crackling in the underbrush. The huge dragon came, lashing its deadly tail, gaping its red jaws, and blowing out poison fumes.

"Ho!" laughed Siegfried. "What a fair comrade I have charmed from his cave! You savage brute, are you going to teach me what fear is?"

"I am going to eat you!" hissed the dragon, glaring at Siegfried and thrusting out its long forked tongue.

Siegfried quickly drew his sword.

Snorting fire and smoke from its nostrils, the monster raised to strike a deadly blow.

Siegfried sprang forward; a flash of steel, and his blade sank to the monster's heart.

As Siegfried drew his blade from the breast of the dying dragon, a drop of its black blood fell on his finger.

It burned like fire.

Siegfried quickly put his finger in his mouth.

The instant the dragon's blood touched his lips, a change came over him.

He could understand the words of the little bird singing in the tree:--

"Now the gold is Siegfried's!

Now all the gold is Siegfried's!

Go into the cave, Siegfried!

Go in! Go in!

Find the helmet and the ring!

The helmet and the ring are Siegfried's!

Take them! Take them! Take them!"

Siegfried went through the brush in the direction from which the monster had come.

When he found the cave, he peered in.

All was deep, dreary darkness, but Siegfried had not learned fear.

He went in and found the gold, the helmet, and the ring.

But he did not need the gold. Its weight would only hinder him.

He looked upon the wishing-cap, but surely no one could turn into anything better than a hero, and Siegfried was already a hero.

What use could he have for a wishing-cap?

A hero does not try to make believe he is something which he is not.

He is brave enough to be just himself.

But the little bird fluttered at the door of the cave.

"Take the helmet and the ring, Siegfried! Take the helmet and the ring!"

"I will obey my little friend," said Siegfried.

The sly, wicked Mimi came slinking to the place where the dragon lay.

When he saw it lying dead under the trees, he looked about for Siegfried, but Siegfried was nowhere to be seen.

"Now I shall rush in and snatch the ring! At last I shall have my pay for all these years of trouble with that rogue I hate!"

But scarcely had Mimi turned toward the dragon's cave when suddenly Alberich sprang before him.

"You sly, crafty rascal!" cried Alberich. "What do you want here? Ha! I have caught you at your sneaking tricks! Long have I guarded here! You shall not steal my gold! Get back to your murky cave."

But Mimi screamed:--

"You shall not have the gold! 'T is mine! Long years have I toiled and waited! The gold is mine, I say!" "Yours?" Alberich snarled in scorn. "Yours? You snatched it from the Rhine-daughters, did you? You paid the price to mould that ring?"

And Mimi raved:

"Who made the helmet, that wondrous cap that in a flash can change a man into anything he wants to be?"

While Mimi and Alberich quarreled, Siegfried came from the dragon's cave, bearing the helmet and the ring.

He heard no sound save the rustling of the leaves and the song of the bird.

Again he sat down in the shadow of a tree.

"Little bird, can you not help me to find a true friend?" asked Siegfried.

"Each year you have your mate and your little birdlings in the nest. You sing songs with the other birds.

"I have never known a father or a mother, a sister or a brother. I am lonely.

"Is there nowhere in all this world some one whom I may love? Some one who will love me?"

Then the wood-bird began to sing a pretty love-song of a maiden sleeping on the crest of a mountain, encircled by fire.

Sweetly he sang:--"Only he who knows no fear may claim her for his bride."

Siegfried sprang to his feet. "I do not know fear. I have tried with all my might to learn it. Oh, help me to find the mountain where she sleeps!"

The little bird flew away in the opposite direction from where the wicked Nibelungs stood quarreling, and Siegfried joyously hurried after.

A heavy storm arose as Siegfried and the bird neared the foot of the mountain where Brunhilde slept. There were peals of deep thunder.

The sky grew very dark. The great boughs of the trees swayed with the wind.

Siegfried took shelter under a low spreading fir.

The storm did not last long, and as the light again broke through the clouds, Siegfried looked about for his little guide, but all in vain. The bird had fled.

Siegfried started on up the mountain, when suddenly the giant Wotan stood before him.

"What are you doing here?" demanded Wotan.

Siegfried replied:--

"I am going to the top of this mountain. There a maiden lies sleeping. I will awaken her, and she shall be my bride."

"Go back to your forest!" commanded Wotan. "This mountain is encircled by fire."

And stretching forth his arm, he barred the path with his mighty spear.

Siegfried quickly drew his sword from its sheath.

"This is the magic spear that rules the world!" said Wotan. "Put away that sword, or the spear that once shattered it will shatter it again!"

"Ha!" cried Siegfried, "then you were my father's foe!"

There was a flash of Siegfried's blade, then a crash that echoed over mountains and valleys, and Siegfried had shattered Wotan's spear. It lay in splinters on the ground.

Wotan stepped aside and sadly bowed his head upon his breast.

He knew this meant the downfall of the giants. No longer would the earth be ruled from fair Valhalla's heights.

Siegfried hurried up the mountain-side.

The fierce flames leaped as if to meet him.

They grew redder, and lapped their fiery tongues.

Siegfried bounded toward them with joy.

Lifting his silver horn to his lips, and blowing his Comrade Call so sweet and clear, he plunged into their depths.

The maddened flames leaped and crackled as if to devour him.

But on he went, blowing his horn, until at length the sea of flames slowly sank to earth.

The redness of the sky gave way to blue, and all grew clear and beautiful.

Siegfried looked upon the sleeping figure.

All the world seemed wrapped in silence. Not a leaf moved on the trees.

There was not a sound to mar that perfect sleep.

Siegfried looked in wonder at the shining coat of mail.

"It is some valiant knight," he whispered.

"How heavy seems the armor. It should be lifted so that he may rest better."

Carefully Siegfried lifted the glittering shield and laid it to one side.

Eagerly he raised the helmet. There fell a mass of waving golden hair. "A burst of glorious sunshine," whispered Siegfried.

Then he sought to loosen the rings that held the coat of mail.

Finding it difficult, he drew his sword and cut them.

The shining armor fell jingling to the ground.

The soft white folds of her woman's gown fell loosely about her.

Siegfried started back and stared in silence.

He trembled from head to foot.

He pressed his hand to his fast-beating heart.

"At last!" he cried. "At last! I know what fear is."

At length Siegfried went softly to Brunhilde's side.

He stood and looked upon her sweet, heroic face, and love came into his heart.

Bending low, he tenderly kissed her.

Brunhilde slowly opened her eyes.

She looked up at the blue sky and the smiling sun, and cried:--

"All hail to thee, thou glorious sun in heaven!"

The flowers slowly opened their petals, the birds began to sing.

Brunhilde's horse awoke and neighed his glad call.

Brunhilde looked upon Siegfried.

Slowly her memory returned.

As she remembered Wotan's words: "Only he who knows no fear may claim you for his bride," she knew at last her hero had come.

She looked into Siegfried's strong, brave face, and as he told her of his love, she no longer wished to go back to Valhalla.

She knew that she loved Siegfried with all her heart, and she promised to be his bride.

She told him that she would always be happy when she was by his side.

One very dark night, three Norns came to the mountain crest to spin.

If you had seen them, you would have called them witches.

They spun the thread of fate.

They were very, very old. The eldest was almost as old as the world.

They were tall and gaunt, and wore long black gowns.

Their faces and hands were deep-wrinkled with age, and their hair was as white as the snow.

They had come up from the great, dark earth-hole, where they lived, and now they crouched upon the rocks to spin their thread.

The eldest was the first to spin the thread, and as she spun, she sang a song about the past, when Wotan and his happy family lived out of doors upon the mountain-side.

She sang of the time when he split from the world's ash tree the piece of wood from which he made the magic spear, which had ruled the world for so many hundreds of years.

She sang of Freya's apples, and of the strength and youth of the giant family.

At length her voice wavered, the strange, weird song ceased, and she tossed the thread to the second Norn.

As the second Norn took the thread in her worn hands, she crooned a sorrowful song about the present.

She sang of Alberich and the stolen gold. Of the love that he had given up in order to make the ring.

She sang of Wotan and how he grasped the ring and carried it into the world, bringing with it Alberich's curse.

Then she told of Fafner.

Mournfully she sang:--

"It has robbed all who have had it of their freedom and happiness.

"It has brought envy and discontent to those who have struggled to gain it.

"Now Wotan's magic spear is splintered.

"Oh! How this gold has tangled all my threads!" she wailed.

Her long, gaunt fingers pulled and worked at the knots, but all in vain.

She could not straighten out the snarls.

"Sing, oh, my Sister, sing!" she cried. "You know what the end will be."

And she tossed the snarled threads to the third Norn.

The third Norn took up the thread.

Twisting and untying, she sang of the future.

She sang of the downfall of the giants.

She sang of the time when Wotan and his family would be no more, and bright Valhalla's halls would be only a ruin.

"But, Sisters, look!" she cried. "The day is dawning. We must make haste!"

She tugged at the thread. The knots grew tighter.

"Oh, see!" she cried. "I cannot make it reach."

Another pull, the thread snapped.

The three Norns wailed.

Then, snatching up the broken ends of their thread of fate, they vanished in the gloom.

The days went by. Siegfried and Brunhilde were perfectly happy upon the mountain.

One day they decided that Siegfried should go forth to do brave deeds in the world.

He would come back when he had won honor and fame.

He told Brunhilde how anxious he would be to get back to her, and that he would come just as soon as he could.

Brunhilde told Siegfried how lonely she would be without him, and how she would listen both day and night for the glad call of his silver horn.

Siegfried took Brunhilde's hand and put the ring upon her finger, saying:--

"This, Brunhilde, shall stay with you. It shall be a pledge of my love until I come again."

Brunhilde gave Siegfried her swift horse. On it he should ride to great victories.

Siegfried led the horse down the mountain.

Every little way he looked lovingly back at Brunhilde.

They called and waved to each other until he passed from sight.

And after that Brunhilde listened to the clear notes of his silver horn, until at length its last faint echo died away.

Siegfried had been away several days.

Brunhilde sat looking far out over the valley.

She was thinking of Siegfried and of how he was proving his courage to the world.

She lifted her hand to her lips and kissed the ring, Siegfried's pledge of love.

"Heiho! hoyotoho! heiho!" came from the valley below.

Brunhilde sprang to her feet with the answer:--

"Heiho! hoyotoho! heiho!"

Could it be that one of her sisters was coming to see her?

Was it possible that one of the Walküre would so far dare Wotan's wrath as to venture to the mountain's crest?

Nearer came the call:--

"Heiho! hoyotoho! heiho!"

And a battle-maiden came in sight.

Brunhilde was very happy to see her sister again, but the battle-maiden looked sad.

She brought bad news from Valhalla.

She and Brunhilde sat down upon the rock, and the battle-maiden told the sad story of the last days of the giants.

"Brunhilde," she said, "Wotan does not know that I have come. Valhalla is in deepest gloom.

"Wotan has never sent us to a battlefield since that day when we last saw you.

"Not long ago he came home with his magic spear broken into splinters. He sat down and buried his face in his hands, and there he sits day after day.

"He tell us the giants are passing from the earth. A little while and Valhalla shall be no more.

"He refuses all of Freya's golden fruit. He has grown very old and very sad.

"Yesterday I heard him say, 'Oh! if Brunhilde would only give the ring back to the Rhine-daughters, and release the world from the terrible curse of gold!'

"And, Brunhilde, I have come to beg of you, will you not give the ring back to the Rhine-daughters?"

Brunhilde clasped the ring close to her breast.

"Give the ring to the Rhine-daughters?" she cried.

Then she looked far away toward the valley----and Siegfried.

"This ring of mine is Siegfried's pledge of love!"

The next morning Brunhilde stood upon Walküre Rock and watched the glorious sunrise.

Suddenly she heard the glad notes of Siegfried's silver horn.

"Siegfried! Siegfried!" she cried in joy, and hurried down the mountain to greet him.

All the earth seemed as glad as at that glad time when Siegfried came to Walküre Rock to claim Brunhilde for his bride.

But Brunhilde was not altogether happy.

She could not forget the sorrowful news which her sister had brought, of the gloom at Valhalla.

So, after their first glad greeting, they sat down upon the rocks, and Brunhilde told Siegfried the sad story of the ring, from the time when Alberich snatched it from the Rhine-daughters, until the day Siegfried took it from Hate Cavern.

Then, hand in hand, they went, the valiant Siegfried and the noble Brunhilde, to the banks of the Rhine.

They called to the Rhine-daughters and the Rhine-daughters came out upon the rocks.

With a glad shout, Brunhilde flung the ring into the water.

The Rhine-daughters darted after it.

In a moment they came again to the surface of the water.

At last they held their precious, glittering gold.

The happiest song that ever echoed along the banks of the Rhine was sung by the Rhine-daughters on that glad morning.

Once more gold had become as harmless as a sunbeam.

Hurry, worry, falsehood, greed, and envy vanished from the earth.

Anxiety disappeared from the brows of the tired fathers.

A new happiness came into the eyes of the loving mothers.

A greater power than gold or giant strength had come to rule the world, and that power was Love.

The author would not have you think that when you have read this little book you know all that Richard Wagner told about Siegfried.

When you are older, do not fail to read The Rhine-Gold, The Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung, as Richard Wagner told them.

You will enjoy them more because of having read these little stories.

End of Project Gutenberg's Opera Stories from Wagner, by Florence Akin

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OPERA STORIES FROM WAGNER ***

***** This file should be named 9456-h.htm or 9456-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.net/9/4/5/9456/

Produced by Project Gutenberg Distributed Proofreaders

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.net/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,